'Principled Adaptability' Blends Realism and Idealism at Work

I and many of my planning colleagues have righteous indignation over calls by the president-elect to roll back social and environmental progress. We are responding through our planning work and renewing our commitment to the ideals of planning. But we must also be realistic.

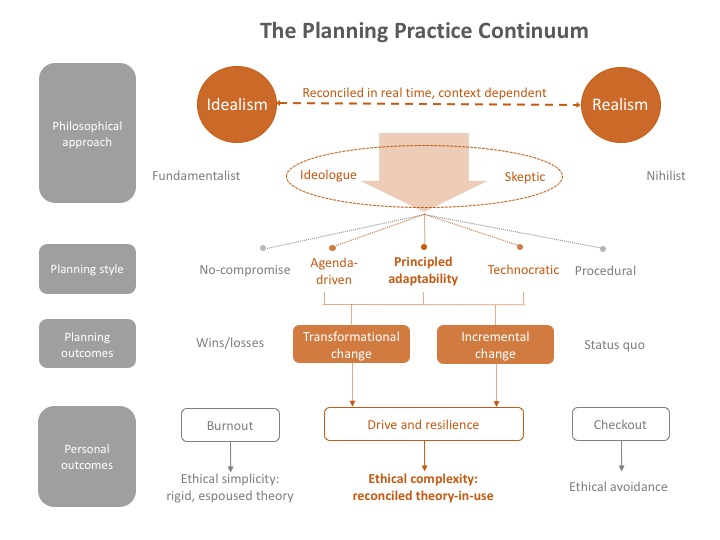

This post addresses the roles of idealism and realism in planning practice, arguing for a planning style called principled adaptability.

Principled adaptability recognizes the ongoing tensions between idealism and realism. It allows for convictions about planning values — the idealism part — and an ability to be effective in environments of uncertainty, controversy, and structural limitations — the realism part.

Principled adaptability keeps the planner engaged within their organization and with external actors and stakeholders. It enables effective, strategic thinking and action.

Idealism and Realism in Planning Practice

The diagram shows planning practice on a continuum between idealism and realism. Each term has philosophical roots that are strongly connected to planning. Effective planners address this tension, issue by issue, and day by day.

This doesn't mean balancing in the middle — sometimes idealism must predominate and other times realism is the best approach.

Four terms are displayed under the idealism/realism continuum. They describe planning-practice responses to that tension. The ellipse is shown to suggest that planners may sometimes act as ideologues, emphasizing values, and other times act as skeptics, emphasizing evidence. More likely is a balancing of these factors to suit the planning issue. Outside the ellipse are fundamentalism and nihilism — less appropriate philosophical approaches to planning.

Shouldn't one's job description determine the planning style?

An environmental review planner, for example, applies evidence and standards in a prescribed manner. A community organizer works primarily in the values realm. So, yes, the job shapes the role. But transportation models are not purely evidence-based nor should evidence be forsaken in community organizing work. There is always some room for selecting an approach within the constraints of a job description and organization setting.

In principled adaptability, the planner has a firm compass direction but is open to learning.

Styles of Planning Practice Continuum

The planner adapts to the political, economic, and social context, and makes strategic choices about role. Using this approach, the planner does not insist on winning every issue and is willing to compromise but focus on progress.

Agenda-driven and technocratic roles are also shown. Agenda-driven planning is propelled by advocacy for issues such as greenhouse gas reduction, social justice, or affordable housing. Technocratic planning is built on evidence, comprehensiveness, and systems.

These three styles — principled adaptability, agenda-driven, and technocratic — are all effective depending on the planning problem, the planner's personality, and job expectations. When lasting transformational and incremental change is achieved, it naturally motivates the planner. Results produce drive and resilience in the face of inevitable disappointments in planning practice.

The extremes on the left and right sides of the diagram are less appealing. The "scorched earth", no-compromise approach leads to wins and losses but can result in personal burnout. On the other hand, a retreat into purely procedural planning reinforces the status quo and can be accompanied by a "check-out" attitude toward the profession.

If principled adaptability has advantages, why doesn't every planner practice in that manner?

The short answer is that it is more challenging than the alternatives. It requires ethical reasoning, humility, and living with uncertainty.

On a particular planning issue, what should be the level of attention to values as compared to evidence? Is compromise or is it selling out? How should short-term and long-term gains and losses be weighed? How does one reconcile personal career success and one's planning values?

Reconciling idealism and realism requires ongoing reflection and decision-making. This may seem like an extra burden of professional planning, but thinking well about ethical choices benefits one's professional career and personal life.

Principled adaptability works. The planners I admire practice it. They are inspired, grounded, and engaged in meaningful work — making a living and making the world a better place.

This blog series is amplified in Richard Willson's book, A Guide for the Idealist: How to Launch and Navigate Your Planning Career. The book includes perspectives, tools, advice, and personal anecdotes. It is available now at Routledge, Amazon, and most retailers.

Top image: Thinkstock photo.