Planning August/September 2018

Planning News

Ongoing Kilauea Volcano Activity Complicates Big Island Recovery

On May 5, 2018, molten lava from Fissure 7 blocked two streets in the Leilani Estates subdivision on Hawaii's Big Island. Photo courtesy USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory.

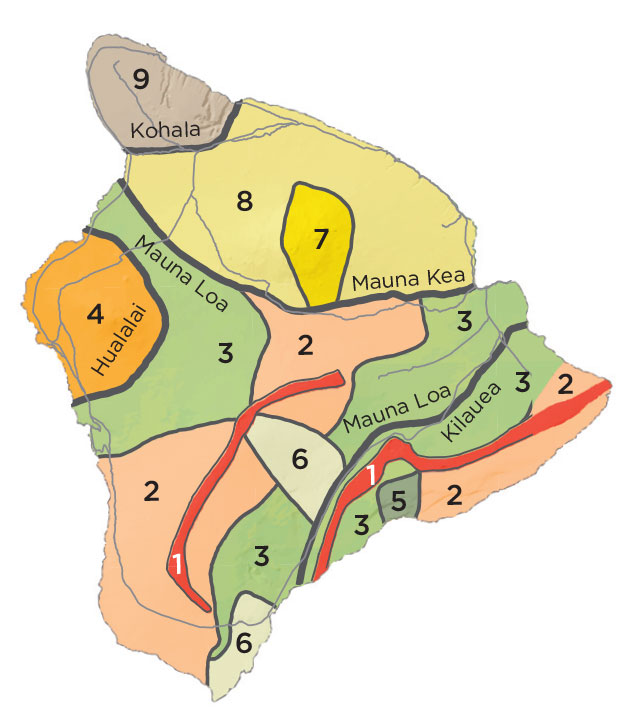

This map depicts the lava-flow hazard zones developed for the Big Island's five volcanoes. Zone 1 (red) is the highest-risk and includes summits and rift zones of Kilauea and Mauna Loa, where vents have been repeatedly active. Zone 2 (orange) includes areas adjacent to and downslope of zone 1. Between 25 and 75 percent of zone 2 has been covered by lava over the last 750 years. Map courtesy Hawaii State Office of Planning.

Rivers of lava seeping from volcanic fissures and plumes of ash soaring into the sky — it sounds like a scene from a Hollywood film, or a nightmare. But it has been a perpetual reality for residents of the island of Hawaii since May 3, when the first of Kilauea's volcanic eruptions began. This latest spike in activity has lava pouring into nearby neighborhoods, destroying homes and displacing more than 2,800 residents.

As of June 28, nearly 10 square miles were covered by lava, and a 400-acre "lava delta" of new land had formed where Fissure 8 is pouring lava into the ocean. A series of earthquakes has also rocked the island, with more than 4,000 mostly small quakes in a single week, and explosions are sending ash plumes and projectiles high into the sky. Mandatory evacuations are in place in some areas and one lava-related and three respiratory-related injuries have been reported.

Numerous roads are closed, as more than 56.9 miles of roadways, including part of Highway 137, are covered with lava. A geothermal plant that provides a quarter of the island's electricity has been shut down for now. And most of Hawaii Volcanoes National Park is closed due to the danger.

The long game

The need for Big Island to plan for volcanic events wasn't unexpected; Kilauea volcano has been active since 1983. But responding to, and recovering from, them is a challenge because no one knows how long they will last.

"[Volcanic events are] different from other types of hazards, which typically have a beginning, a middle, and an end," says Karl Kim, PhD, an urban and regional planning professor at the University of Hawaii. "These are really long, long, long duration events and the hazard or threat doesn't really just go away like a tornado. It's an ongoing threat and it's something that we have to learn to live with and adapt to."

Hawaii was one of the first states in the country to implement volcanic zoning, says Leo Asuncion, AICP, director of the Office of Planning for the State of Hawaii and an APA board member. He notes that the state's volcanic zone overlay has zones ranging from 1 to 9, with 1 having the greatest risk.

Kilauea by the Numbers

As of early June 2018

10 square miles of land buried in lava

57 miles of lava-covered roadways

400 acres of new land created

650 homes lost

2,800 residents displaced

Kim, who also works with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to prepare governments to respond and recover after disasters, says planners intentionally sought to limit growth and development in the most volcanically active zones by limiting infrastructure in those areas. However, that led to lower land costs, and people built on the land despite the danger. It is legal to build in those areas, though it can be difficult to obtain bank loans and home insurance in the most active zones.

"[Residents] all have in the back of their minds the risk that you are in either zone 1 or zone 2 of the volcanic area and you might face an eruption at some time," Asuncion says. "You're kind of playing the odds on when it's going to happen, if it's really going to happen."

As of press time, Asuncion estimates that 650 homes (primarily in zones 1 and 2) have been lost. With several people living in each home on average, that leaves a lot of people in need of shelter. More than 1,000 residents had registered for FEMA assistance as of late June.

The state plans to build tiny homes and other shelters as temporary housing, says Asuncion, who notes that traditional temporary shelters, like school cafeterias, do not work for such long-term events.

Planners' role

While volcanoes are not a common problem for most communities, Kim says planners everywhere can apply the lessons learned in Hawaii and in the Pacific Northwest to other areas of planning.

"There's a lot of uncertainty associated with this, and management of uncertainty is one of the critical roles that I think planners have to do," Kim says. "I would go so far as to say they're really valuable lessons to think about [for] other long-duration events like climate change or sea-level rise."

In some cases, the lesson is less about preventing destruction and more about acknowledging the hazard's inevitability and being as prepared as possible.

For example, planners in Pierce County, Washington, located near Mount Rainier, use their county's comprehensive plan to keep critical facilities such as schools, hospitals, and fire stations out of hazardous areas.

In Skamania County, Washington, where Mount St. Helens erupted in 1980, killing 57 people and spreading ash through a huge swath of the country, the planning department requires people who build in the area to first submit a geotechnical report pertaining to volcanic impacts. While some minor mitigation measures, like requiring the use of nonflammable materials, are possible in certain situations, these reports largely serve to inform the owners of the danger.

"There really is not a lot you can do to protect your property if we have another eruption similar to 1980," says Alan Peters, AICP, assistant planning director for Skamania County. "Your property is probably lost, so it's really being prepared for that event and how to get out of the area."

— Kristen Pope

Pope is a freelance writer and editor in Jackson, Wyoming.

Restored Wetland Stars in Road Project

The newly opened SouthEast Connector road project in the Reno-Sparks metro area in Nevada restored 80 acres of wetlands and added a 5.5-mile connected multiuse path. Photo courtesy Washoe County Regional Transportation Commission.

"It's an environmental project with a road through it," Michael J. Moreno, public affairs manager for the Washoe County Regional Transportation Commission, likes to say.

The road, known as the SouthEast Connector during the years it was planned and built in Nevada's Reno-Sparks metropolitan area, was designed to connect residential areas north of the Truckee River to booming industrial areas to the south, one of which includes Tesla's first Gigafactory, via 5.5 miles of six-lane roadway with three signalized intersections and a 45-mile-per-hour speed limit. Funding for the $300 million project came from an indexed fuel tax that voters passed in 2008.

For commuters, the road replaces a spaghetti bowl of ramps and connectors at the junction of interstates and other highways, says Peter Gower, AICP CEP, chair of the Reno Planning Commission and a consultant with Environmental Management and Planning Solutions, Inc. And, somewhat counterintuitively, for the wetland the project it cut through, the road project has granted a new lease on life.

Up for a (environmental) challenge

In 2009, the board analyzed three different routes for the roadway and selected the only one that would not require condemning anyone's home. That route, however, cut through a wetland.

Normally, messing with a wetland is a bad idea, but in this case, "The wetland was in bad shape," says Lee Gibson, AICP, the RTC's executive director. It was polluted with methylmercury from historical gold and silver mining, and infested with whitetop, an invasive plant also known as hoary cress. The nearby river, Steamboat Creek, had been sunk in a channel that was 12 feet deep in places.

"For a road engineer, roads are simple," says Garth Oksol, the project's former manager, now with a private company. "The environmental aspect was more challenging and more rewarding."

The road project restored 80 acres of wetlands and renovated a total of 300 acres in the project area. That included removing 3.7 million pounds of trash, sloping the river banks to a more natural form, removing invasive plants, planting trees, and scraping up 20,000 pounds of mercury-contaminated soil.

The contaminated soil was "permanently sequestered," Oksol says, in the embankment that keeps the road above the 100-year floodplain. It's topped by the impervious road surface and hemmed in by 15 to 20 feet of clean soil.

But the project was not without controversy. Upper South East Communities Coalition, Inc., a local environmental group, sued the RTC and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers over the environmental impact assessment and approval of a wetlands fill permit for the road.

"If this had been almost any other state, it would have never been approved," says Kimberly Rhodemyre of the coalition. She's frustrated that she and her group could not get answers to their questions about mercury sequestration and flood control, and that public meetings did not include public comment.

In July 2015, the U.S. Court of Appeals Ninth Circuit denied the group's emergency motion for injunctive relief, citing the 300-plus public meetings RTC held about the project as part of its National Environmental Policy Act assessment.

Grand opening

Among the project's first users were the bald eagles that visited the site during construction. Oksol reports that marmots, rabbits, and geese have returned. Willows are taking root. And recently, Oksol says, he saw a squadron of 50 pelicans where he had never seen more than seven before.

On June 30, walkers, runners, and cyclists were given charge of the whole road, not just the multiuse path that runs for 5.5 miles alongside it and connects to an existing bike path. Motorists had to wait until July 6 to use roadway, which has been renamed Veterans Parkway.

— Madeline Bodin

Bodin is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to Planning.

Iowa Town Plans for Burial Space Shortage

Perry, Iowa, has a problem. It's running out of room for its deceased. In a town of only 7,800 people, the largest cemetery will reach capacity within 10 years, despite two previous expansions. Last spring, as the city prepared 17 adjacent acres for a third expansion, City Manager Sven Peterson realized the town needed a better solution, so he turned to his former planning professor for help.

Carlton Basmajian, associate professor of Iowa State University's community and regional planning department, is a published expert in the landscape of death. (He coauthored PAS Report 572, Planning for the Deceased: www.planning.org/publications/report/9026896.) In Perry's problem, he saw an opportunity to introduce his students to the land-use implications of cemeteries and burial.

The class began last spring. By the end of the semester, Perry had its pick of multiple multiuse cemetery designs, several of which, Basmajian says, could be used by other cities facing similar challenges.

Global cemetery squeeze

Perry, Iowa's dilemma is playing out on a global scale. As urban cemeteries face overcrowding, soaring plot prices, and land shortages, cities are scrambling to find alternate lodging for the deceased. In Brazil, cemeteries are going vertical, Jerusalem is reviving catacombs, and China is encouraging cremation despite long-held traditions requiring ground burial.

If 2.4 billion more people join the world's urban population by 2050 as projected, cemeteries will face even more competition for space. In the U.S., the issue will be further complicated by the 76 million aging baby boomers, who will reach average life expectancy before 2042.

Case in point: Perry. "Here [is] a small city, with a stable population, in a low growth state, that was running out of burial space," says Basmajian. "It seemed like an ideal situation for a small planning studio."

During the course — officially dubbed "City of the Dead" — students learned about burial regulations, visited local cemeteries, and developed plans to present to Perry residents. One team suggested a multiuse cemetery with urn vaults, a scattering garden, and public art, along with community engagement to ensure culturally and financially inclusive options.

"We talked a lot about equity in the class," says Basmajian. "One of the biggest unequalizers is the cost of burial. The students recommended a number of ways that the city could reduce the cost and provide services to all parts of the wealth spectrum."

While Perry has yet to commit to a design, Basmajian hopes to stay involved in the process. "I think the solutions that the students came up with could be used by just about any city facing either burial ground shortage or an interest in finding new ways to utilize existing cemeteries as community infrastructure," he says.

A few cities have a head start. LA's Hollywood Forever Cemetery holds public events like movie screenings amid its gravestones. Austin's Historic Cemeteries Master Plan, an effort to transform the city's historic cemeteries into activated public spaces, won a National Planning Achievement Award from APA last year. But many have a long way to go.

"The project is just one small example of a much bigger issue," Basmajian says. "Planners aren't the only ones that should be engaging in this conversation, but they have a unique set of knowledge and skills that would seem to make them ideal leaders of any movement to rethink burial and its meaning for communities in the future."

— Lindsay Nieman

Nieman is Planning's associate editor.

News Briefs

Sales tax can now be collected by states from online retailers without a physical presence in their borders, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in South Dakota v. Wayfair. For more on changes in the retail industry, read Planning's July 2018 cover story, "Retail Realities": www.planning.org/planning/2018/jul/retailrealities.

The first bike share in a Native American territory was launched in Nevada's Reno-Sparks Indian Colony as part of a public-private partnership with the community, LimeBike, Reno, and the University of Nevada. The pilot program started with 1,000 dockless bicycles in May and has since serviced about 21,000 riders on 36,000 trips.

Affordable housing might get its own department in Chicago following a proposal from Mayor Rahm Emanuel. The push follows a Chicago Tribune report indicating that the number of affordable units available is well below the city's estimates. The department would head up the Chicago Opportunity Investment Fund, a new program that helps developers buy apartments in gentrifying neighborhoods in exchange for keeping 20 percent of the units affordable for 15 years.

Michael Bloomberg announced the $70 million American Cities Climate Challenge, a suite of resources and technical support to help the 100 most populous cities in the U.S. reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Billed as a "two-year accelerator," the program puts the focus on the transportation and building sectors. The 20 cities that show the most progress will earn funding, data and design support, and other resources.

Planning News is edited by Mary Hammon, Planning's associate editor. Please send information to her at mhammon@planning.org.