Remembering Chris Kochtitzky: A Conversation on COVID-19

On the night of May 3, I was working on my computer when I heard my wife say, "Sagar, I think Chris passed away." Chills went through my body as I heard those words.

Chris Kochtitzky. Photo courtesy the CDC.

Immediately, I went to the Caring Bridge website and saw the message about Chris Kochtitzky's death. He had been in the hospital for almost two weeks, fighting for his life. It was hard to fathom that my dear friend and mentor, with whom I had just been talking a few days ago, was no longer with us.

Chris was a senior advisor in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity (DNPAO), where he served as an expert on the development of evidence-based guidelines and recommendations to increase physical activity across the country.

He was one of the founders of the field of built environment and health at CDC. I have worked at the intersection of planning and health for more than a decade but have not come across a person who could synthesize planning practice and research with public health practice and research better than Chris.

Chris believed in always giving, and he was known for his ability to make connections — whether between people or between unconnected dots of information. He used to say, "I breathe networking as you breathe air."

Honoring Chris Kochtitzky's Valuable Perspectives

There are so many things to say about Chris — his work at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), his contributions to the field of built environment and health, his dedication to addressing health inequities, or his early days living with parents who were civil rights workers.

You can get a glimpse of Chris's life in a blog post by the CDC and an article in the Jackson Free Press. Some of his work can be found here: Public Health Agents of Change: Chris Kochtitzky, Some of the Biggest Problems Sometimes Have the Simplest Solutions, and Urban Planning and Public Health at CDC.

This blog post is a way for me to remember Chris and honor him. In the final weeks of his life — from March 2 to April 17, 2020 —I received 74 emails from Chris and had several phone conversations with him about the COVID-19 pandemic. We discussed many things, but here I will highlight a few things that Chris, as a planner working in public health for decades, would have liked to share with planners about COVID-19.

Below I have imagined and shared a phone conversation with Chris based on our discussions and the documents he created. The views expressed here do not reflect the views of the CDC; as Chris would often say to me, "I am speaking as a planner and an APA member, not as a CDC employee."

SAGAR SHAH: Thank you for agreeing to provide the public health perspective on the COVID-19 pandemic. This information will be very helpful to our members.

CHRIS KOCHTITZKY: I believe that planners should know about some basic public health concepts related to COVID-19 to effectively work on response and recovery work.

SHAH: What are these concepts or terms that planners should know about COVID-19?

KOCHTITZKY: There are several, but the following will help planners in their personal and professional lives.

COVID-19 Terms and Concepts

Bending the Curve and Raising the Line

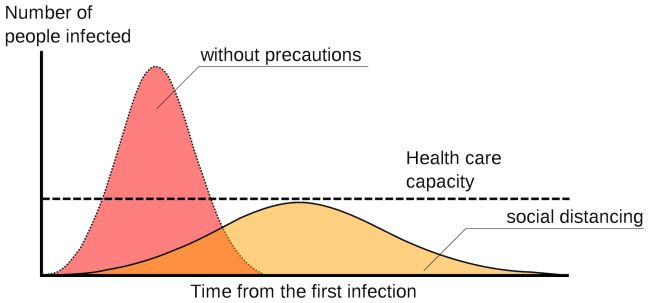

A sample epidemic curve, with and without social distancing. Image by Johannes Kalliauer (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Two factors must be forecasted in planning and preparation: the upward curve representing the growth of cases and the line representing the total number of cases that a healthcare system can handle (usually a combination of available hospital space, equipment, personnel, and supplies). The only way to avoid healthcare collapse is to bend the upward curve down and out while raising the healthcare capacity line upward until the line is higher than the curve.

The Basic Reproduction Number (R0)

Pronounced "R naught" and also called the basic reproduction ratio or rate or the basic reproductive rate, R0 is a metric used to describe the contagiousness or transmissibility of infectious agents. This value is a function of three primary parameters:

- the duration of contagiousness after a person becomes infected,

- the likelihood of infection per contact between a susceptible person and an infectious person or vector,

- and the contact rate between individuals.

Additional parameters can be added to describe more complex cycles of transmission. Thus, R0 is affected by numerous biological, socio-behavioral, and environmental factors that govern pathogen transmission.

Community or Herd Immunity

This occurs when a large enough proportion of a population is immune to an infectious disease (through vaccination and/or prior illness) to make its spread from person to person unlikely (Source: HHS).

Each pathogen has a different herd immunity threshold (HIT), defined as the fraction of a population that must be immune to confer herd immunity on those not protected from a disease. Herd immunity threshold population proportions can vary from 79–84 percent of the population for Diphtheria, which has an R0 of 4 to 5, to 96–to 99 percent of the population for Measles, which has an R0 of 11 to 18. The R0 for the current (in March 2020) novel coronavirus, SARS-COV-2, is currently estimated at somewhere between 2.2 and 5.7. (As per this recent article, the herd immunity threshold for SAR-COV-2 is believed to be 60 percent).

Contact Tracing

The process of identifying, assessing, and managing people who have been exposed to a contagious disease to prevent onward transmission (More information: Kaiser Family Foundation).

SHAH: Physical distancing has been in place for a few months now. What do we need to move away from it?

KOCHTITZKY: Physical distancing measures are working to reduce community transmission, avoid overwhelming our hospitals, and ultimately save lives. But they cannot be sustained indefinitely at this scale. To gradually move away from a reliance on physical distancing as our primary tool for controlling future spread, we need:

- better data to identify areas of spread and the rate of exposure and immunity in the population

- improvements in state and local healthcare system capabilities, public health infrastructure for early outbreak identification, case containment, and adequate medical supplies

- therapeutic, prophylactic, and preventive treatments and better-informed medical interventions that give us the tools to protect the most vulnerable people and help rescue those who may become very sick.

SHAH: We know that vaccination to the degree needed to confer community (herd) immunity is probably the only full and long-term solution to the pandemic. What can you tell us about vaccination and its development?

KOCHTITZKY: Vaccine clinical trials come with three phases, and the first stages of the current COVID-19 trials aren't due for completion until fall 2020, spring 2021, or much later. And there are good reasons to allow time for safety checks.

Some preliminary vaccines for the related coronavirus SARS, for instance, actually enhanced the disease in model experiments. In other cases, vaccines that may have been rushed into use have caused other harm. The 1976 swine flu vaccine was estimated to have caused approximately one Guillain-Barré syndrome case per 100,000 persons vaccinated.

SHAH: What are the economic impacts of this pandemic on our communities?

KOCHTITZKY: There are various implications, as we have seen.

Many cities are braced for budget shortfalls and many are planning cuts and layoffs. For instance, the mayor of San Antonio, Texas, predicts that his municipality will face as much as a $100 million shortfall. In addition, the national unemployment rate will increase, there will be losses in industrial production, and U.S. GDP will contract.

However, it is difficult to gauge exactly how major pandemics affect economic activity in the medium to longer term.

SHAH: What steps are public health departments, healthcare systems, and governments across the country taking to tackle COVID-19? Maybe knowing them would help planners think about supporting that work.

KOCHTITZKY: Various strategies are being employed to fight COVID-19. The most common strategies, irrespective of whether the number of cases is increasing, remaining the same, or decreasing, that are being employed are:

- Greatly scaling up diagnostic testing and previous exposure screening capacity to identify cases and immune

- Growing the number of available hospital and intensive care beds with ventilators and other relevant equipment

- Radically increasing the availability and improving the distribution of necessary supplies, including personal protective equipment, testing swabs, laboratory reagents, and test kits

- Mobilizing a large temporary workforce drawing from current medical and nursing students, returning Peace Corps volunteers, and others

- Scaling up contact tracing and quarantining of close contacts of known COVID-19 cases.

SHAH: Can you offer specific guidance for places or communities where disease is spreading but is still limited?

KOCHTITZKY: For those places where disease spread is still very limited, continue moderate physical distancing along with rigorous case identification, and contact tracing, followed by case and contact isolation.

To slow the spread, schools are closed across the country, workers are being asked to do their jobs from home when possible, community gathering spaces such as malls and gyms are closed, and restaurants are being asked to limit their services.

These measures will need to be in place in each state until transmission has measurably slowed down and health infrastructure can be scaled up to safely manage outbreaks and care for the sick.

SHAH: What is the role of planners in all of this? How can planners help fight this pandemic?

KOCHTITZKY: The best way to think about planners' roles in making our communities resilient to such pandemics is approaching them as events of emergencies such as natural disasters and apply a similar planning lens.

Planners play important roles in all phases of CDC's standard response activity areas mentioned below, which are based on FEMA's mission areas of Technical Assistance Program and FEMA's description of Emergency Management:

- Preparedness: Developing planning, training, and educational activities for events that cannot be mitigated; for example, disaster preparedness plans that identify what to do, where to go, or who to call for help in a disaster.

- Prevention: Developing the capabilities necessary to avoid, prevent, or stop negative outcomes from an event beforehand.

- Protection: Developing the capabilities necessary to immediately secure a community or region against negative outcomes from an event that has occurred.

- Mitigation: Developing the capabilities necessary to initially reduce the loss of life and property by lessening the impact of an event.

- Response: Developing the ongoing capabilities and activities necessary to save lives, protect property and the environment, and meet basic human needs after an incident has occurred.

- Recovery: Developing the core capabilities necessary to assist communities affected by an incident to recover as rapidly, efficiently, and effectively as possible.

Here, I can't emphasize enough that planners need to work with public health departments and other sectors to build resilient communities.

SHAH: How planners can help public health departments in the response and recovery phases?

KOCHTITZKY: Helping with contract tracing is one example. When applied to the U.S. population, a New Zealand-like approach would mean a total of 13,000 contact tracers in this country, a Massachusetts-like approach would mean a total of 50,000, and a Wuhan-like approach would mean more than 265,000.

The contract tracing initiative announced by Massachusetts involves a multiagency and multisectoral coordinated approach that can serve as an example to other states. Planners can play important roles in supporting such initiatives.

SHAH: Thanks for this information, Chris. I am sure this will help planners understand COVID-19 from a public health perspective.

KOCHTITZKY: No problem. Talk with you soon.

Honoring Chris Kochtitzky's Legacy

It is hard to imagine that I will never talk with Chris again. I had personally known Chris only for the last three years, but it felt like we had a special bond. That was a unique quality of Chris's — making people feel that they were special. So, it was no surprise that around 370 people attended his online memorial on May 20, 2020.

Here are a few phrases that people used during the memorial to describe him: very kind soul, touched so many lives, he had the courage to speak truth to power, believed in always giving, we are all lesser because of his passing, he always said: "pay it forward."

His passing is a huge loss to the field. CDC Foundation understands this and has created the Chris Kochtitzky Memorial Fund in his honor to build a bridge between urban planning and public health.

Chris, I will miss you. As one of your friends said, "You were one of the most special people on earth. I'm going to look up in the night sky because I'll bet there is a new shining star up there."

Top image: COVID-19 prevention guidelines. Illustration from the CDC.