Uncovering JAPA

Preserving the Grass Root of Urban Agriculture

We are in an age of smart cities that have become more efficient and responsive through technological advances. Still, we find that despite their benefits, many serve as centers of inequality. This is particularly true in the development of urban food systems.

In "Urban Farming Is Going High Tech," Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 86, No. 1), Michael Carolan investigates the impact of emerging digital urban agriculture (DUA) on traditional urban agriculture. As Carolan characterizes it, digital urban agriculture includes "elements of automation, software, and/or silicon-based hardware" in the growing process.

Digital Urban Agriculture: Views Differ

However, one's perspective on DUA may be tied to one's existing relationship with urban agriculture. Through technology, digital urban agriculture has increased production, but it too has introduced a barrier to participation. Carolan discovers that community-based stakeholders believe DUA impinges on urban agriculture, exploiting it for economic gain and gentrifying agricultural practices.

Whereas funding could support existing — albeit smaller-scale — agriculture or reinvest in other community assets, it is instead put toward DUA.

This contrasts with the view of politicians and technology advocates who see themselves as strengthening communities. They suggest that through new sources of capital, they achieve a stronger tax base to support communities.

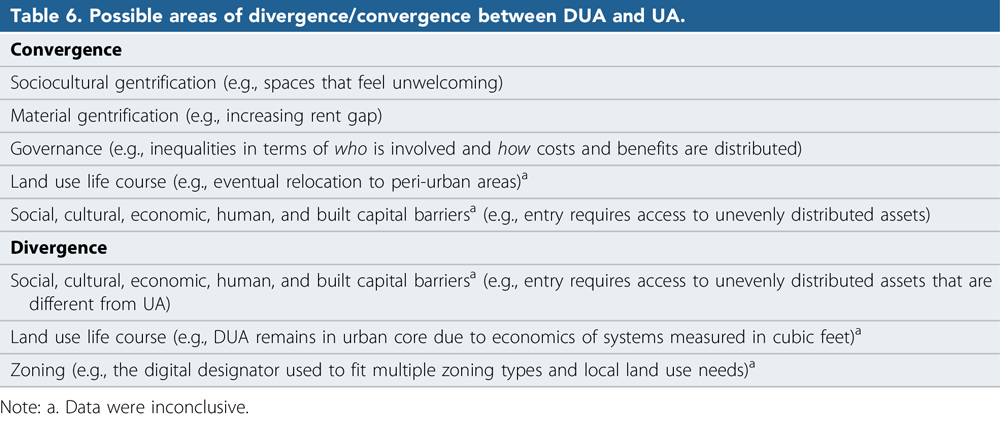

Table 6: Possible areas of divergence/convergence between digital urban agriculture and urban agriculture.

Digital Urban Agriculture's Impact Debated

Carolan argues that the future could be even more problematic. He finds many urban agriculture practitioners believe that as DUA gains popularity it will begin to occupy larger amounts of land. This will push DUA to less dense areas of cities and perhaps simultaneously push urban agriculture out of cities entirely.

Carolan demonstrates that DUA continues to gain the favor of planners, politicians, and the public. Because of this, it has been able to reshape itself to fit into different zoning designations — unseen with urban agriculture.

The future of urban agriculture is uncertain, but this is not the first threat it has faced. Urban agriculture already has become popular among wealthier individuals who have divorced it from its political significance. Now, it seems, DUA is simply the next step.

However, I believe it is possible to move forward with both urban agriculture and DUA. This starts with planners valuing urban agriculture as more than a means of food production but also as a form of resistance and community.

Top image: Preparing the ground at the Brother Nature Produce Urban Farm in Detroit. Photo by Flickr user Michigan Municipal League (CC BY-ND 2.0).