Better Metrics for Communicating Planning Agency Value

Summary

- Process-oriented metrics often fail to communicate the value of planning work to decision-makers and the public.

- Results-oriented metrics are more compelling but harder to connect to planning agency activities.

- Planning agencies can elevate the value of their work by developing performance metrics that bridge process and results, aligning daily activities with broader community goals.

It's an anxious time for planners. Throughout 2025, APA reported on how federal policy shifts have led to reduced funding for local and regional planning projects and growing economic uncertainty. This leaves many planning agencies scrambling to find new sources of project funding, while simultaneously preparing to weather a potential economic downturn.

If we've entered a new period of realignment and redefinition for the profession, what can planners do to better measure and communicate their value to decision-makers and the public?

Since the 1990s, many local planning agencies have used performance data to track progress toward performance-based budgeting and management or strategic planning goals. The most common metrics (a.k.a. key performance indicators) use data about development applications, permits, or customer experiences to track agency performance. In contrast, following the adoption of MAP-21 in 2012, all officially designated metropolitan planning organizations must measure and report on safety, congestion, and other aspects of overall transportation system performance. But are either of these approaches doing enough to demonstrate the value of the day-to-day work of planners?

To better understand the state of the practice and to identify promising new approaches, we recently completed a comprehensive update of the Measuring Planning Department Performance collection in APA's Research KnowledgeBase. Through this update, we noted the persistence of two core tensions related to performance measurement and two emerging practices that show how planners may begin to resolve these tensions.

Core Tensions in Performance Measurement

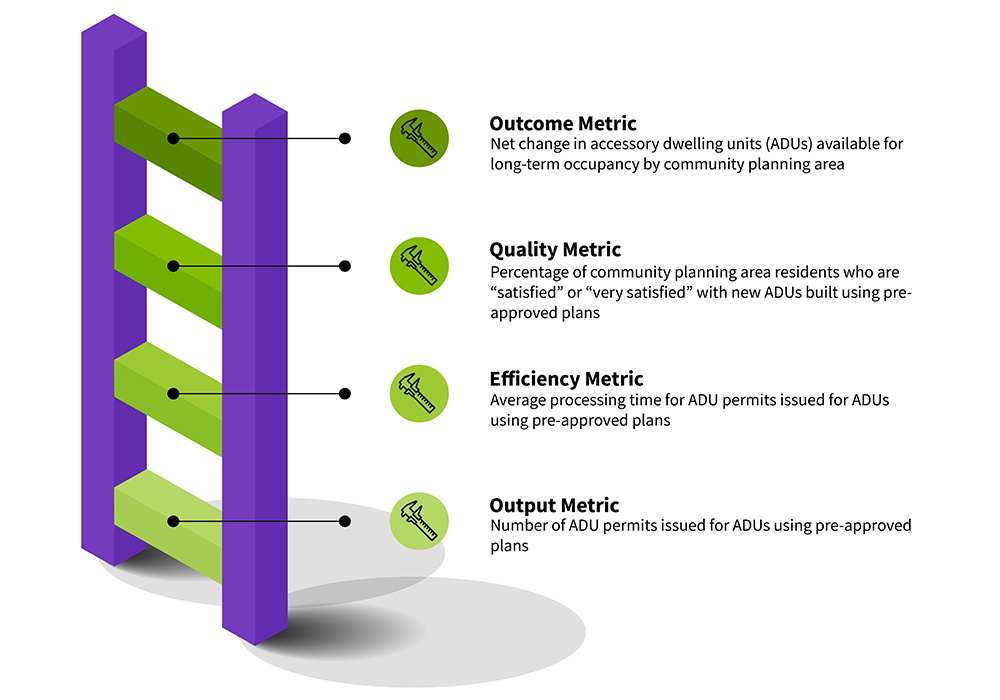

Fundamentally, performance metrics are either "process-oriented" or "results-oriented." Process-oriented metrics look at inputs into a process (e.g., applications received), outputs from a process (e.g., permits issued), or measures of process efficiency (e.g., average application-processing time). Results-oriented metrics help document the quality of a service or product (e.g., percentage of satisfied applicants or participants) or achievement of a desirable outcome (e.g., Walk Score).

Historically, local and regional planning agencies have struggled with what to measure, how often to measure it, and how best to share results with decision-makers and the public. These questions are often complicated at the local level by a need to align performance measurement activities with cross-agency performance-based budgeting and management protocols. And regional planners face a similar challenge in aligning performance metrics with federal requirements for performance-based planning and programming.

Easy Metrics Aren't Always Effective

For most agencies, it's relatively easy and inexpensive to track process-oriented items like the total number of permit counter questions answered, complete development applications submitted, zoning permits processed, or comments received on a draft plan or ordinance. Widely available, intuitive tools like ArcGIS Online, Power BI, and Tableau make real-time, high-quality data visualizations possible and practical for these metrics.

The most readily measurable items often have a clear relationship to the day-to-day work of planning staff (Table 1). However, they may not tell a compelling story (at least not on their own) for elected officials or the public about the value of planning. That is, these metrics can show that planning staffers are hard at work, but they don't necessarily show that this work was worth doing.

Consider the example of metrics tied to the volume or pace of development review activity. One person may see targets met as evidence of regulatory efficiency, while another person may see the metrics themselves as evidence of excessive red tape. And, if the targets must speak for themselves, who's to say which perspective is right?

Numbers Don't Always Tell a Compelling Story

Metrics that track the quality of planning efforts or progress toward broader desirable community outcomes are, typically, more evocative for decision-makers and the public (Table 2). That is, they speak directly to what we're trying to achieve through our work (e.g., a livable built environment, harmony with nature, a resilient economy, etc.). While regional planning agencies routinely track transportation system performance, local planning agencies seldom use metrics to track progress toward community outcomes. And when they do, the emphasis is typically on tracking comprehensive plan implementation and not the direct effects of agency activities.

The high potential for a disconnect between quality or outcomes and agency actions is another core tension. The metrics that resonate the most with decision-makers and the public may be the hardest to connect to the day-to-day work of planners. Consider the example of a housing affordability metric. While planners may have played a crucial role in plan-making and zoning reform efforts that helped to increase housing supply, housing market dynamics are complex, and many factors outside of the control of planning staff affect average housing costs in a community.

Let's Advance the Practice of Performance Measurement

The tensions outlined above make it difficult for planners to effectively communicate the value of their work through routine data collection, analysis, and reporting on their activities. Here are two things planners can do that could go a long way toward resolving these tensions. Some agencies have already taken steps in this direction.

Don't Make Numbers Speak for Themselves

Relatively few common planning agency performance metrics are self-evidently meaningful to elected officials or the public. That means planners must ensure that all process-oriented metrics have a clear relationship to results and that they are explaining those relationships in plain language.

This may be as simple as adding notes to data visualizations that clearly state why the agency is using a particular metric, where the data comes from, and how the metric relates to broader outcomes. For example, Malibu, California, provides data visualizations for nine "Planning Performance Metrics." Each visualization is accompanied by text explaining why the metric is important and how the data is calculated. Minneapolis has taken this approach a step further by weaving data visualizations and illustrated narratives into an ArcGIS StoryMap that summarizes the impact of the city's Community Planning and Economic Development Department in 2024.

Identify Metrics That Bridge Process and Results

It's tempting to say that every public-facing performance metric should be results-oriented. Practically, though, local and regional administrators rely on process-oriented metrics to evaluate progress on strategic planning goals and to inform budgets. For example, if average site plan review times are going up, planning staff may be under-resourced.

Rather than eliminating process-oriented metrics, we should work to identify metrics that bridge process and results. While not every metric will have an obvious connection to broader community goals, performance metrics, as a set, should ladder up to those goals (Figure 1).

For example, Washington, D.C., produces annual performance plans and reports for each office reporting to the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development, and each performance plan includes intermediate-scale objectives and associated performance metrics that connect the daily activities of planning staff to broader community goals.

Similarly, Oklahoma City uses a performance dashboard, updated at the end of each fiscal year, to report on planning department metrics that highlight performance trends for a range of current and long-range planning activities. These metrics address topics as diverse as comprehensive plan policy implementation, bike and pedestrian access, and application-decision times.

If we're able to measure performance in ways that help agency administrators defend budget allocations, while still giving local elected officials something to brag about, we can rest assured that we're delivering value to the communities we serve.

APA's Research KnowledgeBase

APA's Research KnowledgeBase connects APA members to curated collections of topically related resources — including plans, regulations, model codes, guides, articles, reports, and multimedia files. Each collection provides commentary and thematic groupings of resource records with bibliographic information, short descriptions, and links to the resources themselves.

Top image: Dilok Klaisataporn/iStock/Getty Images Plus