Uncovering JAPA

What Does "Just Green Enough" Really Mean?

Summary

- Discover how community voices shaped park planning amid fears of rising housing costs and displacement in Minneapolis.

- Residents favored a minimal park over a destination attraction in hopes of avoiding gentrification and displacement.

- Planners face a challenge of translating the concept of enough" from theory into practice.

Many low-income neighborhoods lack green space. New park investments intended to address this inequity can raise nearby housing costs, fueling residents' concerns about gentrification. Do planners have clear terminology to guide discussions with concerned residents about park planning?

In "Bringing Just Green Enough Down to Earth: Limits and Possibilities for Anti-Gentrification Park Planning" (Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 91, No. 4), Hannah Ramer, Rebecca Walker, Kate Derickson, and Bonnie Keeler highlight the challenges of bridging theory and practice through a case study of a contentious park planning process.

They examine the community consultation and planning for the Upper Harbor Terminal, a new park in Minneapolis. While the redevelopment offered an opportunity to remediate pollution and provide green space, the project faced heightened concerns about gentrification. Drawing on interviews and document review, the research explores how planners and community members discuss gentrification while advocating for environmental justice.

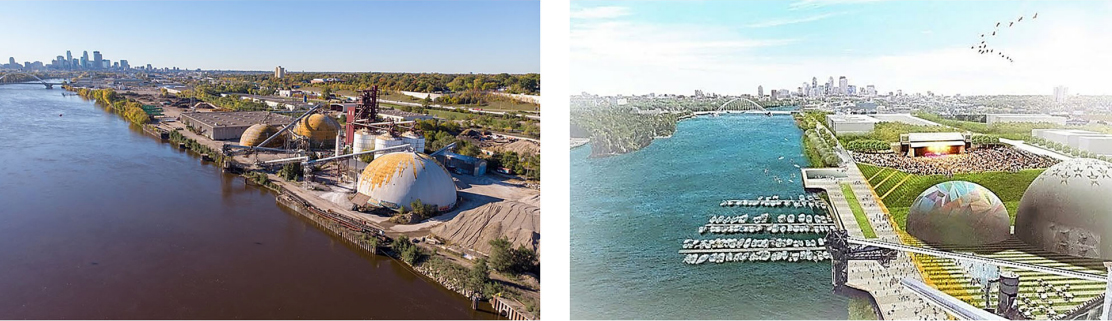

Initial redevelopment designs for the Upper Harbor Terminal. Left: The site before redevelopment, Mississippi Watershed Management Organization, 2018. Right: Initial rendering of the redevelopment, highlighting the green space, concert venue, repurposed industrial structures, and marina (United Properties as cited in Halter, 2016).

Wary Greening

Redeveloping industrial land without displacement is a challenge many cities face. The specific characteristics of a park and the context of redevelopment affect how greening connects to gentrification. Previous research suggests: parks pose a greater gentrification risk than nature preserves or recreation spaces; communal spaces and ecological elements do not spur gentrification; and private funding is linked to gentrification. Context is key, too. A park's effects are shaped by the existing housing stock, transportation access, proximity to downtown, and whether the project is tied to engines of economic development.

Advancing racial equity was a key concern for both the advisory committee and park board planners. As in many cities, redlining, predatory mortgage lending, highway construction, industrial zoning, and park investments have produced enduring racialized wealth and environmental disparities in Minneapolis.

This context contributed to profound distrust of local government during the Upper Harbor Terminal planning process and intensified the pressure to "get it right." Tensions were further heightened by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the murder of George Floyd.

In addition, Minneapolis's Park Board holds an unusual degree of independence. Previous research indicates that siloed governance poses a barrier to addressing green gentrification.

Community Involvement

After the park's boundaries were set, the park board created a community advisory committee composed primarily of residents from nearby north and northeast Minneapolis. The advisory committee met regularly from July 2019 to May 2021 to deliberate and make recommendations to the board of commissioners.

At the fifth advisory committee meeting, park board planners facilitated a discussion on green gentrification. The facilitators acknowledged that, although housing was a crucial factor, it lay outside the park board's control.

A discussion exercise presented a spectrum of park development with two opposing poles: just green enough (JGE) at one end and a destination park at the other. The first term was defined as parks "that satisfy residents' needs but are generally not designed to draw from outside a certain area."

Most participants quickly gravitated toward the JGE option, while questioning what it would mean in practice and whom it would serve. Participants continued to debate the term's meaning in subsequent meetings, never fully coming to an agreement about the meaning or implementation of the concept.

Semi-structured interviews with planners, consultants, and community participants identified several limitations and barriers to the park board's approach to addressing gentrification, including:

- Discursive challenges with just green enough.

- Funding and staffing challenges.

- Questions about who counts as "community" in engagement.

- Lack of authority over other drivers of gentrification.

Diverging Visions

Despite the term's staying power, the facilitating planners were unsure of its origin or precise definition of JGE, noting that they likely encountered it in professional or academic literature.

As the planning process continued, JGE became a malleable signifier for park planning approaches aimed at reducing gentrification risk within the park. For some, JGE primarily meant an emphasis on ecological benefits such as soil remediation, native vegetation, and wildlife habitat.

Others defined JGE by explaining what it was: no zipline, Ferris wheel, large public sculptures, or other landmark amenities that could be a regional draw. One citizen advisory committee member framed JGE as an act of defiance against the growth-oriented city and real estate interests:

I think part of [JGE] is almost like a bit of a protest. Like, "City, if you want to use our park to make your development look shiny and more attractive to your private development team, we're not letting you do that. We're not gonna play your game. We're not gonna cooperate by giving you this luxury amenity that serves the needs of your private development team, who's here to make money."

As the process continued, a core group of four advisory committee members advocated halting park development altogether, largely out of frustration with the city's lack of clear anti-gentrification policies. This advocacy shifted the park planners' initial spectrum of options to include "no park." A subsequent vote presented three possible options: no park, cleanup and restoration only, and JGE. The vote did not find consensus, and planners were left to flesh out a new approach.

In the authors' interviews, one planner argued that JGE was too vague and provided insufficient guidance for design decisions, which sometimes led to confusion or disappointment. A consultant described the concept as "deficit-minded." Another planner drew an analogy with accessibility to critique the term, saying, "We wouldn't ever say to the disability community that we're going to make this 'just accessible enough,' ... it feels like it's minimizing the need."

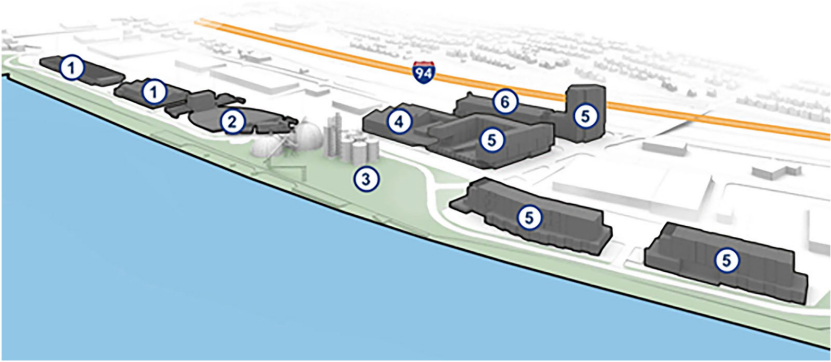

Upper Harbor Terminal redevelopment approved the site plan following Community Advisory Committee input. Modified from City of Minneapolis (2021). Planned land uses include: (1) light industry; (2) 10,000-seat concert venue; (3) park; (4) proposed community wellness hub; (5) 520 units of housing with a mix of affordable and market-rate; and (6) use to-be-determined.

Despite its ambiguity, the final concept plan was named JGE as a guiding principle for the park. The advisory committee's wide-ranging views were translated by planners into the process and goals of redevelopment.

Concerns about displacement and exclusion are captured in the phrase JGE. This case study of park planning is the first to explicitly use the concept. Applied to the park, JGE was interpreted in a variety of ways. For some, it was heralded as a vision for greening without displacement. For others in the park planning process, it meant that low-income communities should limit their vision, undermining the potential for truly reparative park investments. Despite critiques and multiple meanings, JGE persists in academic, professional, and popular presses.

Takeaways for practices:

- Multiple policy arenas must connect to effectively confront green gentrification.

- Regardless of intent, just green enough has limited utility for park planning.

- Just green enough is an interim approach to reduce harm by working within, without challenging the status quo.

- Just green enough shows the unintended consequences of academic concepts translated into planning practice.

- Further work can identify transformative planning concepts and tools that center vulnerable residents' needs while meaningfully integrating greening, housing, and employment.

Top image: Photo by iStock/Getty Images Plus/ Roberto Galan

ABOUT THE AUTHOR