Planning for Utility-Scale Solar Energy Facilities

PAS Memo — September/October 2019

By Darren Coffey, AICP

Solar photovoltaics (PV) are the fastest-growing energy source in the world due to the decreasing cost per kilowatt-hour — 60 percent to date since 2010, according to the U.S. Department of Energy (U.S. DOE n.d.) — and the comparative speed in constructing a facility. Solar currently generates 0.4 percent of global electricity, but some University of Oxford researchers estimate its share could increase to 20 percent by 2027 (Hawken 2017). Utility-scale solar installations are the most cost-effective solar PV option (Hawken 2017).

Transitioning from coal plants to solar significantly decreases carbon dioxide emissions and eliminates sulfur, nitrous oxides, and mercury emissions. As the U.S. Department of Energy states, "As the cleanest domestic energy source available, solar supports broader national priorities, including national security, economic growth, climate change mitigation, and job creation" (U.S. DOE n.d.). As a result, there is growing demand for solar energy from companies (e.g., the "RE100," 100 global corporations committed to sourcing 100 percent renewable electricity by 2050) and governments (e.g., the Virginia Energy Plan commits the state to 16 percent renewable energy by 2022).

Federal and state tax incentives have accelerated the energy industry's efforts to bring facilities online as quickly as possible. This has created a new challenge for local governments, as many are ill-prepared to consider this new and unique land-use option. Localities are struggling with how to evaluate utility-scale solar facility applications, how to update their land-use regulations, and how to achieve positive benefits for hosting these clean energy facilities.

As a land-use application, utility-scale solar facilities are processed as any other land-use permit. Localities use the tools available: the existing comprehensive (general) plan and zoning ordinance. In many cases, however, plans and ordinances do not address this type of use. Planners will need to amend these documents to bring some structure, consistency, and transparency to the evaluation process for utility-scale solar facilities.

Unlike many land uses, these solar installations will occupy vast tracts of land for one or more generations; they require tremendous local resources to monitor during construction (and presumably decommissioning); they can have significant impacts on the community depending on their location, buffers, installation techniques, and other factors (Figure 1); and they are not readily adaptable for another industrial or commercial use, hence the need for decommissioning.

Figure 1. Utility-scale solar facilities are large-scale uses that can have significant land-use impacts on communities. Photo by Flickr user U.S. Department of Energy/Michael Faria.

While solar energy aligns with sustainability goals held by an increasing number of communities, solar industries must bring an overall value to the locality beyond the clean energy label. Localities must consider the other elements of sustainability and make deliberate decisions regarding impacts and benefits to the social fabric, natural environment, and local economy. How should a locality properly evaluate the overall impacts of a large-scale clean energy land use on the community?

This PAS Memo examines utility-scale solar facility uses and related land-use issues. It defines and classifies these facilities, analyzes their land-use impacts, and makes recommendations for how to evaluate and mitigate those impacts. While public officials tend to focus on the economics of these facilities and their overall fiscal impact to the community, the emphasis for planners is on the direct land-use considerations that should be carefully evaluated (e.g., zoning, neighbors, viewsheds, and environmental impacts). Specific recommendations and sample language for addressing utility-scale solar in comprehensive plans and zoning ordinances are provided at the end of the article.

The Utility-Scale Solar Backdrop

In contrast to solar energy systems generating power for on-site consumption, utility-scale solar, or a solar farm, is an energy generation facility that supplies power to the grid. These facilities are generally more than two acres in size and have capacities in excess of one megawatt; today's utility-scale solar facilities may encompass hundreds or even thousands of acres. A solar site may also include a substation and a switchyard, and it may require generator lead lines (gen-tie lines) to interconnect to the grid (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Components of a solar farm: solar panels (left), substation (center), and high-voltage transmission lines (right). Photos courtesy Berkley Group (left, right) and Pixabay (center).

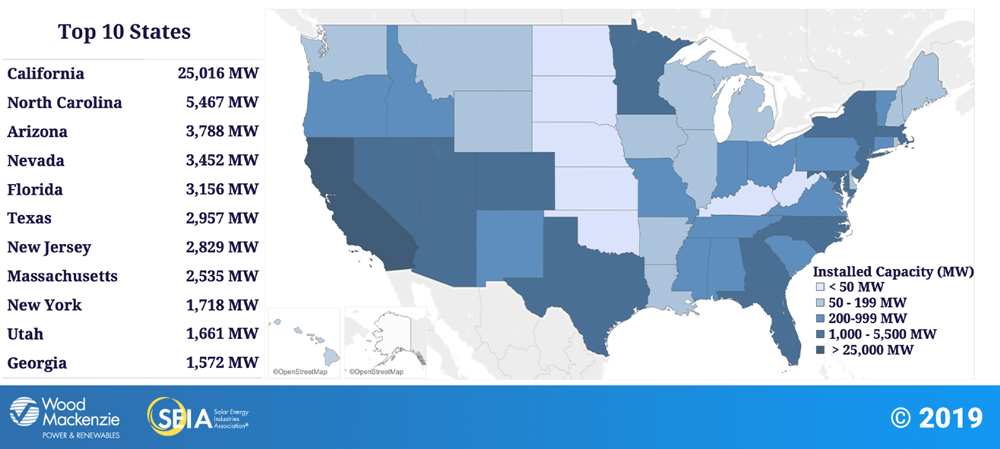

From 2008 to 2019, U.S. solar photovoltaic (PV) installations have grown from generating 1.2 gigawatts (GW) to 30 GW (SEIA 2019). The top 10 states generating energy from solar PV are shown in Figure 3. For many of these initial projects, local planning staff independently compiled information through research, used model ordinances, and relied on professional networks to cobble together local processes and permit conditions to better address the adverse impacts associated with utility-scale solar.

However, each individual project brings unique challenges related to size, siting, compatibility with surrounding uses, mitigating impacts through setbacks and buffers, land disturbance processes and permits, financial securities, and other factors. This has proven to be a significant and ongoing challenge to local planning staff, planning commissions, and governing bodies.

Figure 3. Utility solar capacity in the United States in 2019. Courtesy Solar Energy Industry Association.

Some localities have adopted zoning regulations to address utility-scale solar facilities based on model solar ordinance templates created by state or other agencies for solar energy facilities. However, these ordinances may not be sufficient to properly mitigate the adverse impacts of these facilities on communities. Many of these initial models released in the early 2010s aimed to promote clean energy and have failed to incorporate lessons learned from actual facility development. In addition, the solar industry has been changing at a rapid pace, particularly regarding the increasing scale of facilities. Planners should therefore revisit any existing zoning regulations for utility-scale solar facilities to ensure their relevance and effectiveness.

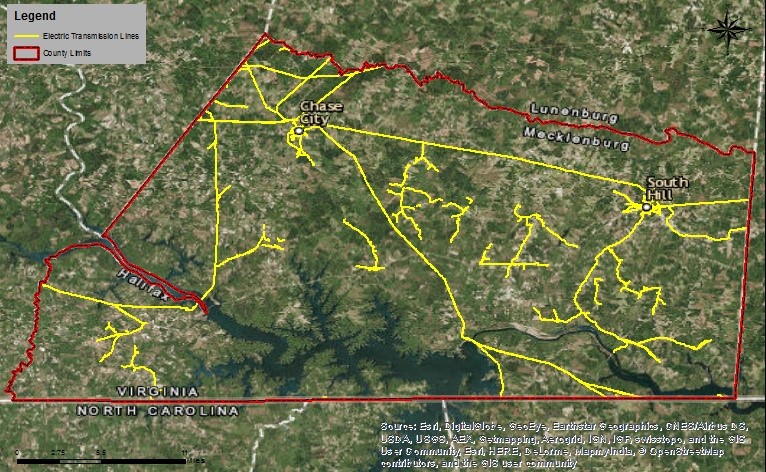

Rapid growth of utility-scale solar facilities has emerged for rural communities, particularly those that have significant electrical grid infrastructure. Many rural counties have thousands of acres of agricultural and forested properties in various levels of production. Land prices tend to be much more cost-effective in rural localities, and areas located close to high-voltage electric transmission lines offer significant cost savings to the industry. Figure 4 shows the extent of existing electric transmission lines in one rural Virginia county.

Figure 4. Electric transmission lines in Mecklenburg County, Virginia. Courtesy Berkley Group.

Federal and state tax incentives have further accelerated the pace of utility-scale solar developments, along with decreasing solar panel production costs. These factors all combine to create land-use development pressure that, absent effective and relevant land-use regulatory and planning tools, creates an environment where it is difficult to properly evaluate and make informed decisions for the community's benefit.

Solar Facility Land-Use Impacts

As with any land-use application, there are numerous potential impacts that need to be evaluated with solar facility uses. All solar facilities are not created equal, and land-use regulations should reflect those differences in scale and impact accordingly.

Utility-scale solar energy facilities involve large tracts of land involving hundreds, if not thousands, of acres. On these large tracts, the solar panels often cover more than half of the land area. The solar facility use is often pitched as "temporary" by developers, but it has a significant duration — typically projected by applicants as up to 40 years.

Establishing such a solar facility use may take an existing agricultural or forestry operation out of production, and resuming such operations in the future will be a challenge. Utility-scale solar can take up valuable future residential, commercial, or industrial growth land when located near cities, towns, or other identified growth areas. If a solar facility is close to a major road or cultural asset, it could affect the viewshed and attractiveness of the area. Because of its size, a utility-scale solar facility can change the character of these areas and their suitability for future development. There may be other locally specific potential impacts. In short, utility-scale solar facility proposals must be carefully evaluated regarding the size and scale of the use; the conversion of agricultural, forestry, or residential land to an industrial-scale use; and the potential environmental, social, and economic impacts on nearby properties and the area in general.

To emphasize the potential impact of utility-scale solar facilities, consider the example of one 1,408-acre (2.2-square-mile) Virginia town with a 946-acre solar facility surrounding its north and east sides. The solar project area is equal to approximately 67 percent of the town's area. A proposed 332.5-acre solar facility west of town increases the solar acres to 1,278.5, nearly the size of the town. Due to its proximity to multiple high-voltage electrical transmission lines, other utility-scale solar facilities are also proposed for this area, which would effectively lock in the town's surrounding land-use pattern for the next generation or more.

The following considerations are some of the important land-use impacts that utility-scale solar may have on nearby communities.

Change in Use/Future Land Use

A primary impact of utility-scale solar facilities is the removal of forest or agricultural land from active use. An argument often made by the solar industry is that this preserves the land for future agricultural use, and applicants typically state that the land will be restored to its previous condition. This is easiest when the land was initially used for grazing, but it is still not without its challenges, particularly over large acreages. Land with significant topography, active agricultural land, or forests is more challenging to restore.

It is important that planners consider whether the industrial nature of a utility-scale solar use is compatible with the locality's vision. Equally as important are imposing conditions that will enforce the assertions made by applicants regarding the future restoration of the site and denying applications where those conditions are not feasible.

Agricultural/Forestry Use. Agricultural and forested areas are typical sites for utility-scale solar facility uses. However, the use of prime agricultural land (as identified by the USDA or by state agencies) and ecologically sensitive lands (e.g., riparian buffers, critical habitats, hardwood forests) for these facilities should be scrutinized.

For a solar facility, the site will need to be graded in places and revegetated to stabilize the soil. That vegetation typically needs to be managed (e.g., by mowing, herbicide use, or sheep grazing) over a long period of time. This prolonged vegetation management can change the natural characteristics of the soil, making restoration of the site for future agricultural use more difficult. While native plants, pollinator plants, and grazing options exist and are continually being explored, there are logistical issues with all of them, from soil quality impacts to compatibility of animals with the solar equipment.

A deforested site can be reforested in the future, but over an additional extended length of time, and this may be delayed or the land left unforested at the request of the landowner at the time of decommissioning. Clearcutting forest in anticipation of a utility-scale solar application should be avoided but is not uncommon. This practice potentially undermines the credibility of the application, eliminates what could have been natural buffers and screening, and eliminates other landowner options to monetize the forest asset (such as for carbon or nutrient credits).

For decommissioning, the industry usually stipulates removal of anything within 36 inches below the ground surface. Unless all equipment is specified for complete removal and this is properly enforced during decommissioning, future agricultural operations would be planting crops over anything left in the ground below that depth, such as metal poles, concrete footers, or wires.

Residential Use. While replacing agricultural uses with residential uses is a more typical land-use planning concern, in some areas this is anticipated and desired over time. "People have to live somewhere," and this should be near existing infrastructure typical of cities, towns, and villages rather than sprawled out over the countryside. This makes land lying within designated growth areas or otherwise located near existing population centers a logical location for future residential use. Designated growth areas can be important land-use strategies to accommodate future growth in a region. Permitting a utility-scale use on such land ties it up for 20–40 years (a generation or two), which may be appropriate in some areas, but not others.

Industrially Zoned Land. Solar facilities can be a good use of brownfields or other previously disturbed land. A challenge in many rural areas, however, is that industrially zoned land is limited, and both public officials and comprehensive plan policies place a premium on industries that create and retain well-paying jobs. While utility-scale solar facilities are not necessarily incompatible with other commercial and industrial uses, the amount of space they require make them an inefficient use of industrially zoned land, for which the "highest and best use" often entails high-quality jobs and an array of taxes paid to the locality (personal property, real estate, machinery and tool, and other taxes).

Location

The location of utility-scale solar facilities is the single most important factor in evaluating an application because of the large amount of land required and the extended period that land is dedicated to this singular use, as discussed above.

Solar facilities can be appropriately located in areas where they are difficult to detect, the prior use of the land has been marginal, and there is no designated future use specified (i.e., not in growth areas, not on prime farmland, and not near recreational or historic areas). Proposed facilities adjacent to corporate boundaries, public rights-of-way, or recreational or cultural resources are likely to be more controversial than facilities that are well placed away from existing homes, have natural buffers, and don't change the character of the area from the view of local residents and other stakeholders.

Concentration of Uses

A concentration of solar facilities is another primary concern. The large scale of this land use, particularly when solar facilities are concentrated, also significantly exacerbates adverse impacts to the community in terms of land consumption, use pattern disruptions, and environmental impacts (e.g., stormwater, erosion, habitat). Any large-scale homogenous land use should be carefully examined — whether it is rooftops, impervious surface, or solar panels. Such concentrated land uses change the character of the area and alter the natural and historic development pattern of a community.

The attraction of solar facilities to areas near population centers is a response to the same forces that attract other uses — the infrastructure is already there (electrical grid, water and sewer, and roads). One solar facility in a given geographic area may be an acceptable use of the land, but when multiple facilities are attracted to the same geography for the same reasons, this tips the land-use balance toward too much of a single use. The willingness of landowners to cooperate with energy companies is understandable, but that does not automatically translate into good planning for the community. The short- and medium-term gains for individual landowners can have a lasting negative impact on the larger community.

Visual Impacts

The visual impact of utility-scale solar facilities can be significantly minimized with effective screening and buffering, but this is more challenging in historic or scenic landscapes. Solar facilities adjacent to scenic byways or historic corridors may negatively impact the rural aesthetic along these transportation routes. Buffering or screening may also be appropriate along main arterials or any public right-of-way, regardless of special scenic or historic designation.

The location of large solar facilities also needs to account for views from public rights-of-way (Figure 5). Scenic or historic areas should be avoided, while other sites should be effectively screened from view with substantial vegetative or other types of buffers. Berms, for example, can provide a very effective screen, particularly if combined with appropriate vegetation.

Figure 5. This scenic vista would be impacted by a solar facility proposed for the far knoll. Photo courtesy Berkley Group.

Decommissioning

The proper decommissioning and removal of equipment and other improvements when the facility is no longer operational presents significant challenges to localities.

Decommissioning can cost millions in today's dollars. The industry strongly asserts that there is a significant salvage value to the solar arrays, but there may or may not be a market to salvage the equipment when removed. Further, the feasibility of realizing salvage value may depend on who removes the equipment — the operator, the tenant, or the landowner (who may not be the same parties as during construction) — as well as when it is removed.

Providing for adequate security to ensure that financial resources are available to remove the equipment is a significant challenge. Cash escrow is the most reliable security for a locality but is the most expensive for the industry and potentially a financial deal breaker. Insurance bonds or letters of credit seem to be the most acceptable forms of security but can be difficult to enforce as a practical matter. The impact of inflation over decades is difficult to calculate; therefore, the posted financial security to ensure a proper decommissioning should be reevaluated periodically — usually every five years or so. The worst possible outcome for a community (and a farmer or landowner) would be an abandoned utility-scale solar facility with no resources available to pay for its removal.

Additional Solar Facility Impacts

In addition to the land-use impacts previously discussed, there are a number of significant environmental and economic impacts associated with utility-scale solar facilities that should be addressed as part of the land-use application process.

Environmental Impacts

While solar energy is a renewable, green resource, its generation is not without environmental impacts. Though utility-scale solar facilities do not generate the air or water pollution typical of other large-scale fossil-fuel power production facilities, impacts on wildlife habitat and stormwater management can be significant due to the large scale of these uses and the resulting extent of land disturbance. The location of sites, the arrangement of panels within the site, and the ongoing management of the site are important in the mitigation of such impacts.

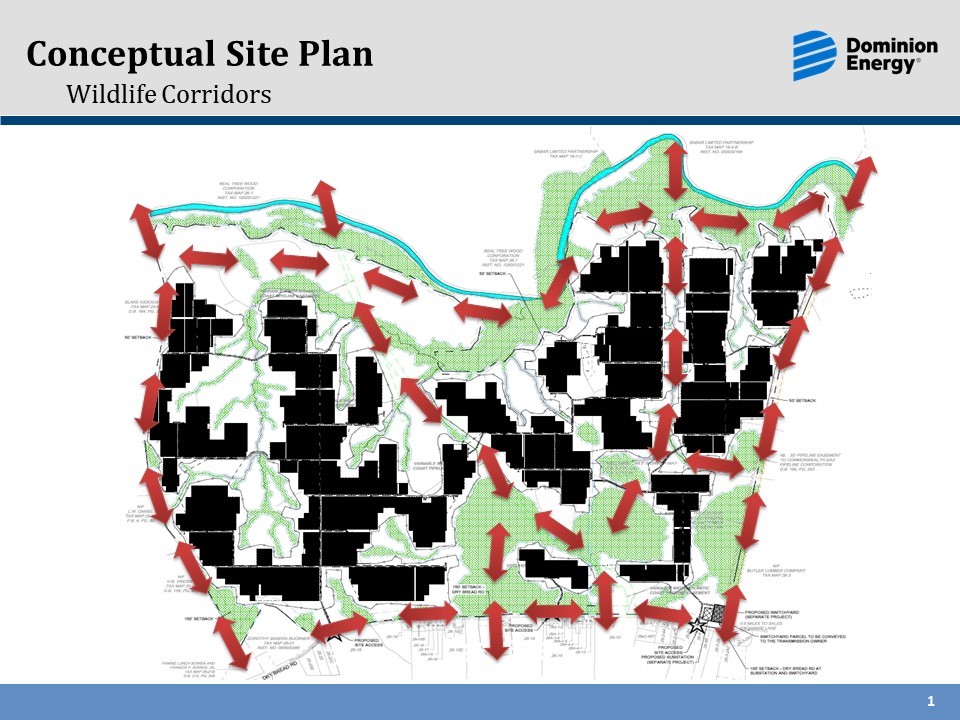

Wildlife Corridors. In addition to mitigating the visual impact of utility-scale solar facilities, substantial buffers can act as wildlife corridors along project perimeters. The arrangement of panels within a project site is also important to maintain areas conducive to wildlife travel through the site. Existing trees, wetlands, or other vegetation that link open areas should be preserved as wildlife cover. Such sensitivity to the land's environmental features also breaks up the panel bay groups and will make the eventual restoration of the land to its previous state that much easier and more effective. A perimeter fence is a barrier to wildlife movement, while fencing around but not in between solar panel bays creates open areas through which animals can continue to travel (Figure 6).

Figure 6. A conceptual site plan for a 1,491-acre utility-scale solar facility showing wildlife corridors throughout the site. Courtesy Dominion Energy.

Stormwater, Erosion, and Sediment Control. The site disturbance required for utility-scale solar facilities is significant due to the size of the facilities and the infrastructure needed to operate them. These projects require the submission of both stormwater (SWP) and erosion/sediment control (ESC) plans to comply with federal and state environmental regulations.

Depending on the site orientation and the panels to be used, significant grading may be required for panel placement, roads, and other support infrastructure. The plan review and submission processes are no different with these facilities than for any other land-disturbing activity. However, such large-scale grading project plans are more complex than those for other uses due primarily to the scale of utility solar. Additionally, the impervious nature of the panels themselves creates stormwater runoff that must be properly controlled, managed, and maintained.

Due to this complexity, it is recommended that an independent third party review all SWP and ESC plans in addition to the normal review procedures. Many review agencies (local, regional, or state) are under-resourced or not familiar with large-scale grading projects or appropriate and effective mitigation measures. It is in a locality's best interest to have the applicant's engineering and site plans reviewed by a licensed third party prior to and in addition to the formal plan review process. Most localities have engineering firms on call that can perform such reviews on behalf of the jurisdiction prior to formal plan review submittal and approval. This extra step, typically paid for by the applicant, helps to ensure the proper design of these environmental protections (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Example of compliance (left) and noncompliance (right) with erosion and sediment control requirements. Photos courtesy Berkley Group.

The successful implementation of these plans and ongoing maintenance of the mitigation measures is also critical and should be addressed in each proposal through sufficient performance security requirements and long-term maintenance provisions.

Cultural, Environmental, and Recreational Resources. Every proposed site should undergo an evaluation to identify any architectural, archaeological, or other cultural resources on or near proposed facilities. Additionally, sites located near recreational, historic, or environmental resources should be avoided. Tourism is recognized as a key sector for economic growth in many regions, and any utility-scale solar facilities that might be visible from a scenic byway, historic site, recreational amenity, or similar resources could have negative consequences for those tourist attractions.

Economic Impacts

This PAS Memo focuses on the land-use impacts of utility-scale solar facilities, but planners should also be aware of economic considerations surrounding these uses for local governments and communities.

Financial Incentives. Federal and state tax incentives benefit the energy industry at the expense of localities. The initial intent of industry-targeted tax credits was to act as an economic catalyst to encourage the development of green energy. An unintended consequence has been to benefit the solar industry by saving it tax costs at the expense of localities, which don't receive the benefit of the full taxable rate they would normally receive.

Employment. Jobs during construction (and decommissioning) can be numerous, but utility-scale solar facilities have minimal operational requirements otherwise. Very large facilities may employ one or two full-time-equivalent employees. During the construction phase there are typically hundreds of employees who need local housing, food, and entertainment.

Fiscal Impact. The positive fiscal impact to landowners who lease or sell property for utility-scale solar facilities is clear. However, the fiscal impact of utility-scale solar facilities to the community as a whole is less clear and, in the case of many localities, may be negligible compared with their overall budget due to tax credits, low long-term job creation, and other factors.

Property values. The impact of utility-scale solar facilities is typically negligible on neighboring property values. This can be a significant concern of adjacent residents, but negative impacts to property values are rarely demonstrated and are usually directly addressed by applicants as part of their project submittal.

Solar Facilities in Local Policy and Regulatory Documents

The two foundational land-use tools for most communities are their comprehensive (general) plans and zoning ordinances. These two land-use documents are equally critical in the evaluation of utility-scale solar facilities. A community's plan should discuss green energy, and its zoning ordinance should properly enable and regulate green energy uses.

The Comprehensive Plan

The comprehensive plan establishes the vision for a community and should discuss public facilities and utilities. However, solar facilities are not directly addressed in many comprehensive plans.

If solar energy facilities are desired in a community, they should be discussed in the comprehensive plan in terms of green infrastructure, environment, and economic development goals. Specific direction should be given in terms of policy objectives such as appropriate locations and conditions. If a community does not desire such large-scale land uses because of their impacts on agriculture or forestry or other concerns, then that should be directly addressed in the plan.

Some states, such as Virginia, require a plan review of public facilities — including utility-scale solar facilities — for substantial conformance with the local comprehensive plan (see Code of Virginia §15.2-2232). This typically requires a review by the planning commission of public utility facility proposals, whether publicly or privately owned, to determine if their general or approximate locations, characters, and extents are substantially in accord with the comprehensive plan.

Most comprehensive plans discuss the types of industry desired by the community, the importance of agricultural operations, and any cultural, recreational, historic, or scenic rural landscape features. An emphasis on tourism, job growth, and natural and scenic resource protection may not be consistent with the use pattern associated with utility-scale solar facilities. If a plan is silent on the solar issue, this may act as a barrier to approving this use. Plans should make clear whether utility-scale solar is desired and, if so, under what circumstances.

This plan review process should precede any other land-use application submittal, though it may be performed concurrently with other zoning approvals. Planners and other public officials should keep in mind that even if a facility is found to be substantially in accord with a comprehensive plan, that does not mean the land-use application must be approved. Use permits are discretionary. If a particular application does not sufficiently mitigate the adverse impacts of the proposed land use, then it can and should be denied regardless of its conformance with the comprehensive plan.

Similarly, in Virginia, a utility-scale solar facility receiving use permit approval without a comprehensive plan review may not be in compliance with state code. The permit approval process is a two-step process, with the comprehensive plan review preferably preceding the consideration of a use permit application.

The Zoning Ordinance

While a community's comprehensive plan is its policy guide, the zoning ordinance is the regulatory document that implements that policy. Plans are advisory in nature, although often upheld in court decisions, whereas ordinance regulations are mandatory. In addition to comprehensive plan amendments, the zoning ordinance should specifically set forth the process and requirements necessary for the evaluation of a utility-scale solar application.

In zoning regulations, uses may be permitted either by right (with or without designated performance measures such as use and design standards) or as conditional or special uses, which require discretionary review and approval. Solar facilities generating power for on-site use are typically regulated as by-right uses depending on their size and location.

Utility-scale solar facilities, however, should in most cases be conditionally permitted regardless of the zoning district and are most appropriate on brownfield sites, in remote areas, or in agriculturally zoned areas. This is particularly true for more populated areas due to the more compact nature of land uses. There are, however, areas throughout the country where utility-scale solar might be permitted by right under strict design standards that are compatible with community objectives.

To better mitigate the potential adverse impacts of utility-scale solar facilities, required application documents should include the following:

- Concept plan

- Site plan

- Construction plan

- Maintenance plan

- Erosion and sediment control and stormwater plans

Performance measures should address these issues:

- Setbacks and screening

- Plan review process

- Construction/deconstruction mitigation and associated financial securities

- Signage

- Nuisance issues (glare, noise)

The model specific planning and zoning recommendations below outline comprehensive plan and zoning ordinance amendments, the application process, and conditions for consideration during the permitting process.

The Virginia Experience

The recommendations presented in this PAS Memo are derived from research and the author's direct experience with the described planning, ordinance amendment, and application and regulatory processes in the following three Virginia localities, all rural counties in the southern or eastern parts of the state.

Mecklenburg County

When Mecklenburg County began seeing interest in utility-scale solar facilities, the county's long-range plan did not address solar facilities, and the zoning ordinance was based on an inadequate and outdated state model that did not adequately regulate this land use.

The town of Chase City is located near the confluence of several high-voltage utility lines, and all proposed facilities were located near or within the town's corporate limits. The county approved the first utility-scale solar facility application in the jurisdiction without any conditions or much consideration. When the second application for a much larger facility (more than 900 acres) came in soon after, with significant interest from other potential applicants as well, the county commissioned the author's consulting firm, The Berkley Group, to undertake a land-use and industry study regarding utility-scale solar facilities.

As Mecklenburg officials continued with the approval process on the second utility-scale solar facility under existing regulations, they received the results of the industry study and began considering a series of amendments to the comprehensive plan and zoning ordinance. Though county officials were particularly worried about the potential concentration of facilities around Chase City, town officials expressed formal support for the proposed land use. Other Mecklenburg communities expressed more concern and wanted the facilities to be located a significant distance away from their corporate boundaries. These discussions led to standards limiting the concentration of facilities, encouraging proximity to the electrical grid, and establishing distances from corporate boundaries where future solar facilities could not be located.

Since the adoption of the new regulations, numerous other utility-scale solar applications have been submitted and while some have been denied, most have been approved. Solar industry representatives' concerns that the new regulations were an attempt to prevent this land use have therefore not been realized; these are simply the land-use tools that public officials wanted and needed to appropriately evaluate solar facility applications. Many of the examples and best practices recommended in this article, including the model language provided at the end of the article, are a result of the utility-scale solar study commissioned by the county (Berkley Group 2017) and the subsequent policies and regulations it adopted.

Sussex County

Sussex County is located east and north of Mecklenburg, and the interest in utility-scale solar projects there has been no less immediate or profound. The announcement of the new Amazon headquarters in Arlington, Virginia, along with the company's interest in offsetting its operational energy use with green energy sources furthered interest in this rural county more than 100 miles south of Arlington.

As in Mecklenburg County, local regulations did not address utility-scale solar uses, so public officials asked for assistance from The Berkley Group to develop policies and regulations appropriate for their community. Sussex County officials outlined an aggressive timeline for considering new regulations regarding solar facilities and, within one month of initiation, swiftly adopted amended regulations for solar energy facilities.

The same metrics and policy issues examined and adopted for Mecklenburg County were used for the initial discussion in Sussex at a joint work session between the board of supervisors (the governing body) and the planning commission. Public officials tailored the proposed standards and regulations to the county context based on geography, cultural priorities, and other concerns. They then set a joint public hearing for their next scheduled meeting to solicit public comment.

Under Virginia law, land-use matters may be considered at a joint public hearing with a recommendation from the planning commission going to the governing body and that body taking action thereafter. This is not a typical or recommended practice for local governments since it tends to limit debate, transparency, and good governance, but due to the intense interest from the solar industry, coupled with the lack of land-use regulations addressing the proposed utility-scale solar uses, county officials utilized that expedited process.

No citizens and only two industry officials spoke at the public hearing, and after two hours of questions, discussion, and some negotiation of proposed standards, the new regulations were adopted the same evening.

Since the new regulations have been put into place, no new solar applications have been received, but informal discussions with public officials and staff suggest that interest from the industry remains strong.

Greensville County

Greensville County, like Mecklenburg, lies on the Virginia-North Carolina boundary. The county has processed four solar energy applications to date (three were approved and one was denied) and continues to process additional applications. Concurrently, the county is in the process of evaluating its land-use policies and regulations, which were amended in late 2016 at the behest of solar energy interests.

The reality of the land-use approval process has proved more challenging than the theory of the facilities when considered a few years ago. As with other localities experiencing interest from the solar energy industry, the issues of scale, concentration, buffers/setbacks, and other land-use considerations have been debated at each public hearing for each application. Neighbors and families have been divided, and lifelong relationships have been severed or strained. The board of supervisors has found it difficult in the face of their friends, neighbors, and existing corporate citizens to deny applications that otherwise might not have been approved.

County officials have agreed that they do want to amend their existing policies and regulations to be more specific and less open to interpretation by applicants and citizens. One of their primary challenges has been dedicating the time to discuss proposed changes to their comprehensive plan and zoning ordinance. A joint work session between the board of supervisors and planning commission is being scheduled and should lead to subsequent public hearings and actions by those respective bodies to enact new regulations for future utility-scale solar applicants.

Action Steps for Planners

There are four primary actions that planners can pursue with their planning commissions and governing bodies to ensure that their communities are ready for utility-scale solar.

Review and Amend the Plan

The first, and most important, step from a planning viewpoint is to review and amend the comprehensive plan to align with how a community wants to regulate utility-scale solar uses. Some communities don't want them at all, and many cities and towns don't have the land for them. Larger municipalities and counties around the country may have to deal with this land use at some point, if they haven't already. Local governments should get their planning houses in order by amending plans before the land-use applications arrive.

Review and Amend Land-Use Ordinances

Once the plan is updated, the next step is to review and amend land-use ordinances (namely the zoning ordinance) accordingly. These ordinances are vital land-use tools that need to be up to date and on point to effectively regulate large and complex solar facilities. If local governments do not create regulations for utility-scale solar facilities, applications for these projects will occupy excessive staff time, energy, and talents, resulting in much less efficient and more open-ended results.

Evaluate Each Application Based on Its Own Merits

This should go without saying, but it is important, particularly from a legal perspective, that each project application is evaluated based on its own merits. All planners have probably seen a project denied due to the politics at play with regard to other projects: "That one shouldn't have been approved so we're going to deny this one." "The next one is better so this one needs to be denied."

The focus of each application should be on the potential adverse impacts of the project on the community and what can be done successfully to mitigate those impacts. Whether the applicant is a public utility or a private company, the issues and complexities of the project are the same. The bottom line should never be who the applicant is; rather, it should be whether the project's adverse impacts can be properly mitigated so that the impact to the community is positive.

Learn From Others

Mecklenburg County's revised solar energy policies and regulations began with emails and phone calls to planning colleagues to see how they had handled utility-scale solar projects in their jurisdictions. The primary resources used were internet research, other planners, and old-fashioned planner ingenuity and creativity.

While it is the author's hope and intent that this article offers valuable information on this topic, nothing beats the tried and true formula of "learn from and lean on your colleagues."

Conclusion

The solar energy market is having major impacts on land use across the country, and federal and state tax incentives have contributed to a flood of applications in recent years. While the benefits of clean energy are often touted, the impacts of utility-scale solar facilities on a community can be significant. Applicants often say that a particular project will "only" take up some small percentage of agricultural, forestry, or other land-use category — but the impact of these uses extends beyond simply replacing an existing (or future) land use. Fiscal benefit to a community is also often cited as an incentive, but this alone is not a compelling reason to approve (or disapprove) a land-use application.

The scale and duration of utility-scale solar facilities complicate everything from the land disturbance permitting process through surety requirements. If not done properly, these uses can change the character of an area, altering the future of communities for generations.

Local officials need to weigh these land-use decisions within the context of their comprehensive plan and carefully consider each individual application in terms of the impact that it will have in that area of the community, not only by itself but also if combined with additional sites. The concentration of solar facilities is a major consideration in addition to their individual locations. A solar facility located by itself in a rural area, close to major transmission lines, not prominently visible from public rights-of-way or adjacent properties, and not located in growth areas, on prime farmland, or near cultural, historic, or recreational sites may be an acceptable land use with a beneficial impact on the community.

Properly evaluating and, to the extent possible, mitigating the impacts of these facilities by carefully controlling their location, scale, size, and other site-specific impacts is key to ensuring that utility-scale solar facilities can help meet broader sustainability goals without compromising a community's vision and land-use future.

Specific Planning and Zoning Recommendations for Utility-Scale Solar

This guidance and sample ordinance language for utility-scale solar facilities is drawn from actual comprehensive plan and zoning ordinance amendments as well as conditional (special) use permit conditions. These examples are from Virginia and should be tailored to localities within the context of each state's enabling legislation regarding land use.

The Comprehensive (General) Plan

The following topics should be addressed for comprehensive plan amendments:

- Identification of major electrical facility infrastructure (i.e., transmission lines, transfer stations, generation facilities, etc.)

- Identification of growth area boundaries around each city, town, or appropriate population center

- Additional public review and comment opportunities for land-use applications within a growth area boundary, within a specified distance from an identified growth area boundary, or within a specified distance from identified population centers (e.g., city or town limits)

- Recommended parameters for utility-scale solar facilities, such as:

- maximum acreage or density (e.g., not more than two facilities within a two-mile radius) to mitigate the impacts related to the scale of these facilities

- maximum percent usage (i.e., "under panel" or impervious surface) of assembled property to mitigate impacts to habitat, soil erosion, and stormwater runoff

- location adjacent or close to existing electric transmission lines

- location outside of growth areas or town boundary or a specified distance from an identified growth boundary

- location on brownfields or near existing industrial uses (but not within growth boundaries)

- avoidance of or minimization of impact to prime farmland as defined by the USDA

- avoidance of or minimization of impact to the viewshed of any scenic, cultural, or recreational resources (i.e., large solar facilities may not be seen from surrounding points that are in line-of-sight with a resource location)

- Identification of general conditions to mitigate negative effects, including the following:

- Concept plan compliance

- Buffers and screening (e.g., berms, vegetation, etc.)

- Third-party plan review (for erosion and sediment controls, stormwater management, grading)

- Setbacks

- Landscaping maintenance

- Decommissioning plan and security

The Zoning Ordinance

In addition to, or separate from, comprehensive plan amendments, the zoning ordinance should be amended to more specifically set forth the process and requirements necessary for a thorough land-use evaluation of an application.

Recommended Application Process

Pre-Application Meeting

The process of requiring applicants to meet with staff prior to the submission of an application often results in a better, more complete application and a smoother process once an application is submitted. This meeting allows the potential applicant and staff to sit down to discuss the location, scale, and nature of the proposed use and what will be expected during that process. The pre-application meeting is one of the most effective tools planners can use to ensure a more efficient, substantive process.

Comprehensive Plan Review

As discussed in the article, a comprehensive plan review for public utility facilities, if required, can occur prior to or as part of the land-use application process. Any application not including the review would be subject to such review in compliance if required by state code. If the plan review is not done concurrently with the land-use application, then it should be conducted prior to the receipt of the application.

An application not substantially in accord with the comprehensive plan should not be recommended for approval, regardless of the conditions placed on the use. Depending on the location, scale, and extent of the project, it is difficult to sufficiently mitigate the adverse impacts of a project that does not conform with the plan.

Land-Use Application

If the comprehensive plan review is completed and the project is found to be in compliance with the comprehensive plan, then the use permit process can proceed once a complete application is submitted. Application completion consists of the submission of all requirements set forth in the zoning ordinance and is at the discretion of the zoning administrator if there is any question as to what is required or when it is required.

Applications should contain all required elements at the time of submittal and no components should be outstanding at the time of submittal.

Sample Ordinance Language

The following sample ordinance language addresses requirements for applications, public notice, development standards, decommissioning, site plan review, and other process elements.

1. Application requirements. Each applicant requesting a use permit shall submit the following:

- A complete application form.

- Documents demonstrating the ownership of the subject parcel(s).

- Proof that the applicant has authorization to act upon the owner's behalf.

- Identification of the intended utility company who will interconnect to the facility.

- List of all adjacent property owners, their tax map numbers, and addresses.

- A description of the current use and physical characteristics of the subject parcels.

- A description of the existing uses of adjacent properties and the identification of any solar facilities — existing or proposed — within a five-mile radius of the proposed location.

- Aerial imagery which shows the proposed location of the solar energy facility, fenced areas and driveways with the closest distance to all adjacent property lines, and nearby dwellings, along with main points of ingress/egress.

- Concept plan.

The facility shall be constructed and operated in substantial compliance with the approved concept plan, with allowances for changes required by any federal or state agency. The project shall be limited to the phases and conditions set forth in the concept plan that constitutes part of this application, notwithstanding any other state or federal requirements. No additional phasing or reduction in facility size shall be permitted, and no extensions beyond the initial period shall be granted without amending the use permit. The concept plan shall include the subject parcels; the proposed location of the solar panels and related facilities; the location of proposed fencing, driveways, internal roads, and structures; the closest distance to adjacent property lines and dwellings; the location of proposed setbacks; the location and nature of proposed buffers, including vegetative and constructed buffers and berms; the location of points of ingress/egress; any proposed construction phases.

- A detailed decommissioning plan (see item 5 below).

- A reliable and detailed estimate of the costs of decommissioning, including provisions for inflation (see item 5 below).

- A proposed method of providing appropriate escrow, surety, or security for the cost of the decommissioning plan (see item 5 below).

- Traffic study modelling the construction and decommissioning processes. Staff will review the study in cooperation with the state department of transportation or other official transportation authority.

- An estimated construction schedule.

- [x number of] hard copy sets (11"× 17" or larger), one reduced copy (8½"× 11"), and one electronic copy of site plans, including elevations and landscape plans as required. Site plans shall meet the requirements of this ordinance.

- The locality may require additional information deemed necessary to assess compliance with this section based on the specific characteristics of the property or other project elements as determined on a case by case basis.

- Application fee to cover any additional review costs, advertising, or other required staff time.

2. Public notice.

- Use permits shall follow the public notice requirements as set forth in the zoning ordinance or by state code as applicable.

- Neighborhood meeting: A public meeting shall be held prior to the public hearing with the planning commission to give the community an opportunity to hear from the applicant and ask questions regarding the proposed project.

- The applicant shall inform the zoning administrator and adjacent property owners in writing of the date, time, and location of the meeting, at least seven but no more than 14 days in advance of the meeting date.

- The date, time, and location of the meeting shall be advertised in the newspaper of record by the applicant, at least seven but no more than 14 days in advance of the meeting date.

- The meeting shall be held within the community, at a location open to the general public with adequate parking and seating facilities which may accommodate persons with disabilities.

- The meeting shall give members of the public the opportunity to review application materials, ask questions of the applicant, and make comments regarding the proposal.

- The applicant shall provide to the zoning administrator a summary of any input received from members of the public at the meeting.

3. Minimum development standards.

- No solar facility shall be located within a reasonable radius of an existing or permitted solar facility, airport, or municipal boundary.

- The minimum setback from property lines shall be a reasonable distance (e.g., at least 100 feet) and correlated with the buffer requirement.

- The facilities, including fencing, shall be significantly screened from the ground-level view of adjacent properties by a buffer zone of a reasonable distance extending from the property line that shall be landscaped with plant materials consisting of an evergreen and deciduous mix (as approved by staff), except to the extent that existing vegetation or natural landforms on the site provide such screening as determined by the zoning administrator. In the event that existing vegetation or landforms providing the screening are disturbed, new plantings shall be provided which accomplish the same. Opaque architectural fencing may be used to supplement other screening methods but shall not be the primary method.

- The design of support buildings and related structures shall use materials, colors, textures, screening, and landscaping that will blend the facilities to the natural setting and surrounding structures.

- Maximum height of primary structures and accessory buildings shall be a reasonable height as measured from the finished grade at the base of the structure to its highest point, including appurtenances (e.g., 15 feet). The board of supervisors may approve a greater height based upon the demonstration of a significant need where the impacts of increased height are mitigated.

- All solar facilities must meet or exceed the standards and regulations of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), State Corporation Commission (SCC) or equivalent, and any other agency of the local, state, or federal government with the authority to regulate such facilities that are in force at the time of the application.

- To ensure the structural integrity of the solar facility, the owner shall ensure that it is designed and maintained in compliance with standards contained in applicable local, state, and federal building codes and regulations that were in force at the time of the permit approval.

- The facilities shall be enclosed by security fencing on the interior of the buffer area (not to be seen by other properties) of a reasonable height. A performance bond reflecting the costs of anticipated fence maintenance shall be posted and maintained. Failure to maintain the security fencing shall result in revocation of the use permit and the facility's decommissioning.

- Ground cover on the site shall be native vegetation and maintained in accordance with established performance measures or permit conditions.

- Lighting shall use fixtures as approved by the municipality to minimize off-site glare and shall be the minimum necessary for safety and security purposes. Any exceptions shall be enumerated on the concept plan and approved by the zoning administrator.

- No facility shall produce glare that would constitute a nuisance to the public.

- Any equipment or situations on the project site that are determined to be unsafe must be corrected within 30 days of citation of the unsafe condition.

- Any other condition added by the planning commission or governing body as part of a permit approval.

4. Coordination of local emergency services. Applicants for new solar energy facilities shall coordinate with emergency services staff to provide materials, education and/or training to the departments serving the property with emergency services in how to safely respond to on-site emergencies.

5. Decommissioning. The following requirements shall be met:

- Utility-scale solar facilities which have reached the end of their useful life or have not been in active and continuous service for a reasonable period of time shall be removed at the owner's or operator's expense, except if the project is being repowered or a force majeure event has or is occurring requiring longer repairs; however, the municipality may require evidentiary support that a longer repair period is necessary.

- Decommissioning shall include removal of all solar electric systems, buildings, cabling, electrical components, security barriers, roads, foundations, pilings, and any other associated facilities, so that any agricultural ground upon which the facility or system was located is again tillable and suitable for agricultural uses. The site shall be graded and reseeded to restore it to as natural a condition as possible, unless the land owner requests in writing that the access roads or other land surface areas not be restored, and this request is approved by the governing body (other conditions might be more beneficial or desirable at that time).

- The site shall be regraded and reseeded to as natural condition as possible within a reasonable timeframe after equipment removal.

- The owner or operator shall notify the zoning administrator by certified mail, return receipt requested, of the proposed date of discontinued operations and plans for removal.

- Decommissioning shall be performed in compliance with the approved decommissioning plan. The governing body may approve any appropriate amendments to or modifications of the decommissioning plan.

- Hazardous material from the property shall be disposed of in accordance with federal and state law.

- The applicant shall provide a reliable and detailed cost estimate for the decommissioning of the facility prepared by a professional engineer or contractor who has expertise in the removal of solar facilities. The decommissioning cost estimate shall explicitly detail the cost and shall include a mechanism for calculating increased removal costs due to inflation and without any reduction for salvage value. This cost estimate shall be recalculated every five (5) years and the surety shall be updated in kind.

- The decommissioning cost shall be guaranteed by cash escrow at a federally insured financial institution approved by the municipality before any building permits are issued. The governing body may approve alternative methods of surety or security, such as a performance bond, letter of credit, or other surety approved by the municipality, to secure the financial ability of the owner or operator to decommission the facility.

- If the owner or operator of the solar facility fails to remove the installation in accordance with the requirements of this permit or within the proposed date of decommissioning, the municipality may collect the surety and staff or a hired third party may enter the property to physically remove the installation.

6. Site plan requirements. In addition to the site plan requirements set forth in the zoning ordinance, a construction management plan shall be submitted that includes:

- Traffic control plan (subject to state and local approval, as appropriate)

- Delivery and parking areas

- Delivery routes

- Permits (state/local)

Additionally, a construction/deconstruction mitigation plan shall also be submitted including:

- Hours of operation

- Noise mitigation (e.g., construction hours)

- Smoke and burn mitigation (if necessary)

- Dust mitigation

- Road monitoring and maintenance

7. The building permit must be obtained within [18 months] of obtaining the use permit and commencement of the operation shall begin within [one year] from building permit issuance.

8. All solar panels and devices are considered primary structures and subject to the requirements for such, along with the established setbacks and other requirements for solar facilities.

9. Site maintenance.

- Native grasses shall be used to stabilize the site for the duration of the facility's use.

- Weed control or mowing shall be performed routinely and a performance bond reflecting the costs of such maintenance for a period of [six (6) months] shall be posted and maintained. Failure to maintain the site may result in revocation of the use permit and the facility's decommissioning.

- Anti-reflection coatings. Exterior surfaces of the collectors and related equipment shall have a nonreflective finish and solar panels shall be designed and installed to limit glare to a degree that no after image would occur towards vehicular traffic and any adjacent building.

- Repair of panels. Panels shall be repaired or replaced when either nonfunctional or in visible disrepair.

10. Signage shall identify the facility owner, provide a 24-hour emergency contact phone number, and conform to the requirements set forth in the Zoning Ordinance.

11. At all times, the solar facility shall comply with any local noise ordinance.

12. The solar facility shall not obtain a building permit until evidence is given to the municipality that an electric utility company has a signed interconnection agreement with the permittee.

13. All documentation submitted by the applicant in support of this permit request becomes a part of the conditions. Conditions imposed by the governing body shall control over any inconsistent provision in any documentation provided by the applicant.

14. If any one or more of the conditions is declared void for any reason, such decision shall not affect the remaining portion of the permit, which shall remain in full force and effect, and for this purpose, the provisions of this are hereby declared to be severable.

15. Any infraction of the above-mentioned conditions, or any zoning ordinance regulations, may lead to a stop order and revocation of the permit.

16. The administrator/manager, building official, or zoning administrator, or any other parties designated by those public officials, shall be allowed to enter the property at any reasonable time, and with proper notice, to check for compliance with the provisions of this permit.

Example of Recommended Use Permit Conditions (In Virginia: Conditional Uses, Special Uses, Special Exceptions)

Conditions ([approved/revised] at the Planning Commission meeting on [date])

If the Board determines that the application furthers the comprehensive plan's goals and objectives and that it meets the criteria set forth in the zoning ordinance, then the Planning Commission recommended the following conditions to mitigate the adverse effects of this utility-scale solar generation facility with any Board recommendation for permit approval.

1. The Applicant will develop the Solar Facility in substantial accord with the Conceptual Site Plan dated _______ included with the application as determined by the Zoning Administrator. Significant deviations or additions, including any enclosed building structures, to the Site Plan will require review and approval by the Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors.

2. Site Plan Requirements. In addition to all State site plan requirements and site plan requirements of the Zoning Administrator, the Applicant shall provide the following plans for review and approval for the Solar Facility prior to the issuance of a building permit:

- Construction Management Plan. The Applicant shall prepare a Construction Management Plan for each applicable site plan for the Solar Facility, and each plan shall address the following:

- Traffic control methods (in coordination with the Department of Transportation prior to initiation of construction), including lane closures, signage, and flagging procedures.

- Site access planning directing employee and delivery traffic to minimize conflicts with local traffic.

- Fencing. The Applicant shall install temporary security fencing prior to the commencement of construction activities occurring on the Solar Facility.

- Lighting. During construction of the Solar Facility, any temporary construction lighting shall be positioned downward, inward, and shielded to eliminate glare from all adjacent properties. Emergency and safety lighting shall be exempt from this construction lighting condition.

- Construction Mitigation Plan. The Applicant shall prepare a Construction Mitigation Plan for each applicable site plan for the Solar Facility to the satisfaction of the Zoning Administrator. Each plan shall address, at a minimum, the effective mitigation of dust, burning operations, hours of construction activity, access and road improvements, and handling of general construction complaints.

- Grading plan. The Solar Facility shall be constructed in compliance with the County-approved grading plan as determined and approved by the Zoning Administrator or his designee prior to the commencement of any construction activities and a bond or other security will be posted for the grading operations. The grading plan shall:

- Clearly show existing and proposed contours;

- Note the locations and amount of topsoil to be removed (if any) and the percent of the site to be graded;

- Limit grading to the greatest extent practicable by avoiding steep slopes and laying out arrays parallel to landforms;

- Require an earthwork balance to be achieved on-site with no import or export of soil;

- Require topsoil to first be stripped and stockpiled on-site to be used to increase the fertility of areas intended to be seeded in areas proposed to be permanent access roads which will receive gravel or in any areas where more than a few inches of cut are required;

- Take advantage of natural flow patterns in drainage design and keep the amount of impervious surface as low as possible to reduce stormwater storage needs.

- Erosion and Sediment Control Plan. The County will have a third-party review with corrections completed prior to submittal for Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) review and approval. The owner or operator shall construct, maintain, and operate the project in compliance with the approved plan. An E&S bond (or other security) will be posted for the construction portion of the project.

- Stormwater Management Plan. The County will have a third-party review with corrections completed prior to submittal for DEQ review and approval. The owner or operator shall construct, maintain, and operate the project in compliance with the approved plan. A stormwater control bond (or other security) will be posted for the project for both construction and post construction as applicable and determined by the Zoning Administrator.

- Solar Facility Screening and Vegetation Plan. The owner or operator shall construct, maintain, and operate the facility in compliance with the approved plan. A separate security shall be posted for the ongoing maintenance of the project's vegetative buffers in an amount deemed sufficient by the Zoning Administrator.

- The Applicant will compensate the County in obtaining an independent third-party review of any site plans or construction plans or part thereof.

- The design, installation, maintenance, and repair of the Solar Facility shall be in accordance with the most current National Electrical Code (NFPA 70) available (2017 version or later as applicable).

3. Operations.

- Permanent Security Fence. The Applicant shall install a permanent security fence, consisting of chain link, 2-inch square mesh, 6 feet in height, surmounted by three strands of barbed wire, around the Solar Facility prior to the commencement of operations of the Solar Facility. Failure to maintain the fence in a good and functional condition will result in revocation of the permit.

- Lighting. Any on-site lighting provided for the operational phase of the Solar Facility shall be dark-sky compliant, shielded away from adjacent properties, and positioned downward to minimize light spillage onto adjacent properties.

- Noise. Daytime noise will be under 67 dBA during the day with no noise emissions at night.

- Ingress/Egress. Permanent access roads and parking areas will be stabilized with gravel, asphalt, or concrete to minimize dust and impacts to adjacent properties.

4. Buffers.

- Setbacks.

- A minimum 150-foot setback, which includes a 50-foot planted buffer as described below, shall be maintained from a principal Solar Facility structure to the street line (edge of right-of-way) where the Property abuts any public rights-of-way.

- A minimum 150-foot setback, which includes a 50-foot planted buffer as described below, shall be maintained from a principal Solar Facility structure to any adjoining property line which is a perimeter boundary line for the project area.

- Screening. A minimum 50-foot vegetative buffer (consisting of existing trees and vegetation) shall be maintained. If there is no existing vegetation or if the existing vegetation is inadequate to serve as a buffer as determined by the Zoning Administrator, a triple row of trees and shrubs will be planted on approximately 10-foot centers in the 25 feet immediately adjacent to the security fence. New plantings of trees and shrubs shall be approximately 6 feet in height at time of planting. In addition, pine seedlings will be installed in the remaining 25 feet of the 50-foot buffer. Ancillary project facilities may be included in the buffer as described in the application where such facilities do not interfere with the effectiveness of the buffer as determined by the Zoning Administrator.

- Wildlife corridors. The Applicant shall identify an access corridor for wildlife to navigate through the Solar Facility. The proposed wildlife corridor shall be shown on the site plan submitted to the County. Areas between fencing shall be kept open to allow for the movement of migratory animals and other wildlife.

5. Height of Structures. Solar facility structures shall not exceed 15 feet, however, towers constructed for electrical lines may exceed the maximum permitted height as provided in the zoning district regulations, provided that no structure shall exceed the height of 25 feet above ground level, unless required by applicable code to interconnect into existing electric infrastructure or necessitated by applicable code to cross certain structures (e.g. pipelines).

6. Inspections. The Applicant will allow designated County representatives or employees access to the facility at any time for inspection purposes as set forth in their application.

7. Training. The Applicant shall arrange a training session with the Fire Department to familiarize personnel with issues unique to a solar facility before operations begin.

8. Compliance. The Solar Facility shall be designed, constructed, and tested to meet relevant local, state, and federal standards as applicable.

9. Decommissioning.

- Decommissioning Plan. The Applicant shall submit a decommissioning plan to the County for approval in conjunction with the building permit. The purpose of the decommissioning plan is to specify the procedure by which the Applicant or its successor would remove the Solar Facility after the end of its useful life and to restore the property for agricultural uses.

- Decommissioning Cost Estimate. The decommissioning plan shall include a decommissioning cost estimate prepared by a State licensed professional engineer.

- The cost estimate shall provide the gross estimated cost to decommission the Solar Facility in accordance with the decommissioning plan and these conditions. The decommissioning cost estimate shall not include any estimates or offsets for the resale or salvage values of the Solar Facility equipment and materials.

- The Applicant, or its successor, shall reimburse the County for an independent review and analysis by a licensed engineer of the initial decommissioning cost estimate.

- The Applicant, or its successor, will update the decommissioning cost estimate every 5 years and reimburse the County for an independent review and analysis by a licensed engineer of each decommissioning cost estimate revision.

- Security.

- Prior to the County's approval of the building permit, the Applicant shall provide decommissioning security in one of the two following alternatives:

- Letter of Credit for Full Decommissioning Cost: A letter of credit issued by a financial institution that has (i) a credit Rating from one or both of S&P and Moody's of at least A from S&P or A2 from Moody's and (ii) a capital surplus of at least $10,000,000,000; or (iii) other credit rating and capitalization reasonably acceptable to the County, in the full amount of the decommissioning estimate; or

- Tiered Security:

- 10 percent of the decommissioning cost estimate to be deposited in a cash escrow at a financial institution reasonably acceptable to the County; and

- 10 percent of the decommissioning cost estimate in the form of a letter of credit issued by a financial institution that has (i) a credit rating from one or both of S&P and Moody's of at least A from S&P or A2 from Moody's and (ii) a capital surplus of at least $10,000,000,000, or (iii) other credit rating and capitalization reasonably acceptable to the County, with the amount of the letter of credit increasing by an additional 10 percent each year in years 2–9 after commencement of operation of the Solar Facility; and

- The Owner, not the Applicant, will provide its guaranty of the decommissioning obligations. The guaranty will be in a form reasonably acceptable to the County. The Owner, or its successor, should have a minimum credit rating of (i) Baa3 or higher by Moody's or (ii) BBB- or higher by S&P; and

- In the tenth year after operation, the Applicant will have increased the value of the letter of credit to 100 percent of the decommissioning cost estimate. At such time, the Applicant may be entitled to a return of the 10 percent cash escrow.

- Upon the receipt of the first revised decommissioning cost estimate (following the 5th anniversary), any increase or decrease in the decommissioning security shall be funded by the Applicant or refunded to Applicant (if permissible by the form of security) within 90 days and will be similarly trued up for every subsequent five-year updated decommissioning cost estimate.

- The security must be received prior to the approval of the building permit and must stay in force for the duration of the life span of the Solar Facility and until all decommissioning is completed. If the County receives notice or reasonably believes that any form of security has been revoked or the County receives notice that any security may be revoked, the County may revoke the special use permit and shall be entitled to take all action to obtain the rights to the form of security.

- Prior to the County's approval of the building permit, the Applicant shall provide decommissioning security in one of the two following alternatives:

- Applicant/Property Owner Obligation. Within 6 months after the cessation of use of the Solar Facility for electrical power generation or transmission, the Applicant or its successor, at its sole cost and expense, shall decommission the Solar Facility in accordance with the decommissioning plan approved by the County. If the Applicant or its successor fails to decommission the Solar Facility within 6 months, the property owners shall commence decommissioning activities in accordance with the decommissioning plan. Following the completion of decommissioning of the entire Solar Facility arising out of a default by the Applicant or its successor, any remaining security funds held by the County shall be distributed to the property owners in a proportion of the security funds and the property owner's acreage ownership of the Solar Facility.

- Applicant/Property Owner Default; Decommissioning by the County.

- If the Applicant, its successor, or the property owners fail to decommission the Solar Facility within 6 months, the County shall have the right, but not the obligation, to commence decommissioning activities and shall have access to the property, access to the full amount of the decommissioning security, and the rights to the Solar Facility equipment and materials on the property.

- If applicable, any excess decommissioning security funds shall be returned to the current owner of the property after the County has completed the decommissioning activities.

- Prior to the issuance of any permits, the Applicant and the property owners shall deliver a legal instrument to the County granting the County (1) the right to access the property, and (2) an interest in the Solar Facility equipment and materials to complete the decommissioning upon the Applicant's and property owner's default. Such instrument(s) shall bind the Applicant and property owners and their successors, heirs, and assigns. Nothing herein shall limit other rights or remedies that may be available to the County to enforce the obligations of the Applicant, including under the County's zoning powers.

- Equipment/Building Removal. All physical improvements, materials, and equipment related to solar energy generation, both surface and subsurface components, shall be removed in their entirety. The soil grade will also be restored following disturbance caused in the removal process. Perimeter fencing will be removed and recycled or reused. Where the current or future landowner prefers to retain the fencing, these portions of fence will be left in place.

- Infrastructure Removal. All access roads will be removed, including any geotextile material beneath the roads and granular material. The exception to removal of the access roads and associated culverts or their related material would be upon written request from the current or future landowner to leave all or a portion of these facilities in place for use by that landowner. Access roads will be removed within areas that were previously used for agricultural purposes and topsoil will be redistributed to provide substantially similar growing media as was present within the areas prior to site disturbance.

- Partial Decommissioning. If decommissioning is triggered for a portion, but not the entire Solar Facility, then the Applicant or its successor will commence and complete decommissioning, in accordance with the decommissioning plan, for the applicable portion of the Solar Facility; the remaining portion of the Solar Facility would continue to be subject to the decommissioning plan. Any reference to decommissioning the Solar Facility shall include the obligation to decommission all or a portion of the Solar Facility whichever is applicable with respect to a particular situation.

10. Power Purchase Agreement. At the time of the Applicant's site plan submission, the Applicant shall have executed a power purchase agreement with a third-party providing for the sale of a minimum of 80% of the Solar Facility's anticipated generation capacity for not less than 10 years from commencement of operation. Upon the County's request, the Applicant shall provide the County and legal counsel with a redacted version of the executed power purchase agreement.

About the Author