Partnering with Health Systems on Affordable Housing Investments

PAS Memo — March-April 2021

This edition of PAS Memo is available free to all.

By Alyia Gaskins

Affordable housing is critical to equitable development. Stable, quality housing that people can afford is at the core of ensuring access to economic, social, and educational opportunities and forestalling displacement.

Unfortunately, affordable housing is in short supply in many areas of the United States. Too many individuals and families spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing, reducing the share of their budget available for food, medical care, and other necessities. Without an intentional focus on increasing the supply of affordable housing, strategies for equitable development are unlikely to succeed.

In the wake of the 2020 economic downturn due to COVID-19, housing insecurity continues to grow, making innovative housing partnerships even more important. Health institutions across the country are well aware of how the social determinants of health (community conditions such as the availability of jobs, affordable housing, and grocery stores) shape health disparities. Many have already begun to explore how they can advocate for, invest in, and provide services at affordable housing developments in their communities (Figure 1).

This PAS Memo explains why and how planners can partner with hospitals and health systems to create more equitable communities. It draws from the experiences of six hospitals and health systems participating in Accelerating Investments for Healthy Communities (AIHC), a three-year initiative of the Center for Community Investment (CCI) at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

This Memo begins by defining equitable development and community investment. It outlines the motivations that bring hospitals and health systems to community investment and the assets these institutions bring to their communities. Case studies explore how health institutions have partnered with planners to deepen and accelerate equitable development. It ends with action steps to help planners cultivate such partnerships with an intentional focus on racial equity, which is critical to equitable development.

Figure 1. Boston Medical Center partnered with the city of Boston to create Bartlett Station, a mixed-use development with affordable housing, housing for people experiencing homelessness, and community-based retail (Boston Medical Center)

Community Investment and Equitable Development

Equitable development typically refers to a range of strategies to ensure that all people, regardless of their race, ethnicity, gender, or income, can participate in and benefit from investment in their community. Preserving and developing affordable housing is a critical component of equitable development.

Equitable development has increasingly gained traction among planning professionals and related institutions. Over the past decade, the American Planning Association has created six policy guides — most recently the 2019 Planning for Equity Policy Guide — and a Social Equity Research KnowledgeBase Collection to support planners in "building equitable, inclusive communities of lasting value."

Key to implementing equitable development strategies is community investment. CCI defines community investment as financing intended to improve social, economic, and environmental conditions in disadvantaged communities while producing some economic return for investors.

Community investments finance small businesses, affordable housing, grocery stores, and other improvements at the core of equitable economic development goals. Since the 1960s, the community investment sector has actively worked to drive capital to disinvested neighborhoods and regions that are underserved by mainstream financial systems. These neighborhoods stand to benefit the most from equitable development and are at risk of losing the most when equity is not prioritized.

To counteract the pressures of the market, successful equitable development requires the support and participation of the public, private, philanthropic, and nonprofit sectors. By engaging with the community investment system, one of the primary engines of equitable development, planners can bring new actors and resources to the table, including anchor institutions: hospitals, universities, local foundations, and other organizations rooted in their communities.

Many anchor institutions already support their communities through charitable contributions, procurement, and recruitment. But when they collaborate with planners, including through community investment, they can help create long-term, sustainable change.

In particular, hospitals and health systems, which have strong interests in building healthy communities and broad arrays of assets (including purchasing power, financial resources, land, and expertise), can be powerful partners in equitable development and community investment. By facilitating these partnerships, planners can play a critical role in supporting equitable development and addressing the urgent challenges of this moment.

The Importance of Affordable Housing

Expanding access to affordable homes is an essential component of equitable development. High housing costs limit opportunities for social and economic mobility and force individuals and families to make financial choices that threaten their stability and health. Additionally, rising housing costs may displace long-time residents, shattering the aspirations for mixed-income communities found in many land-use plans.

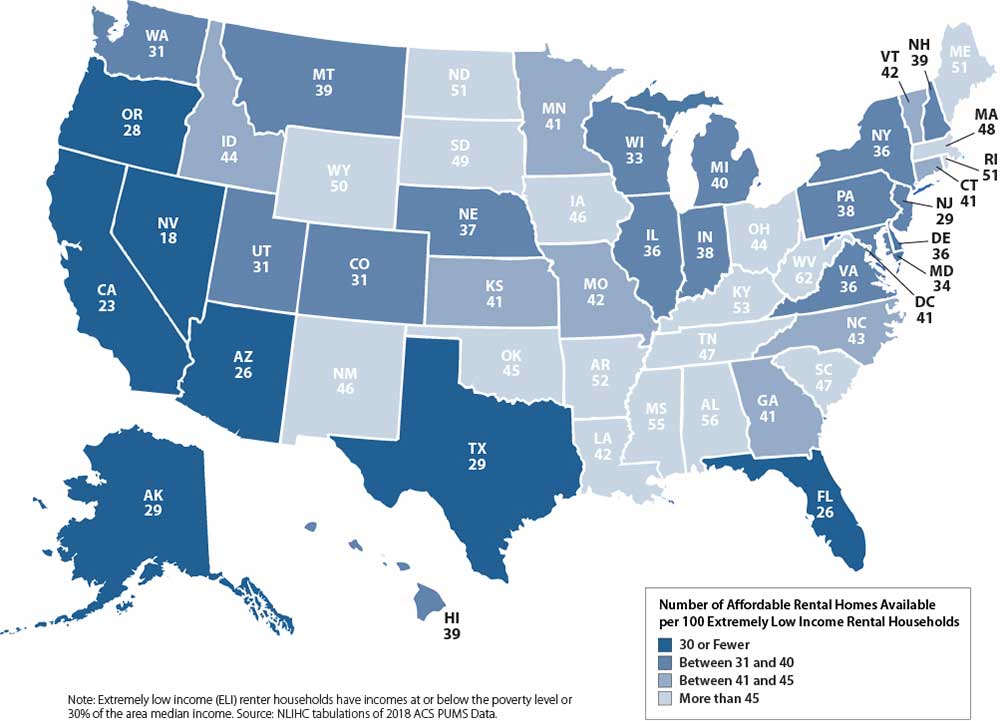

The United States currently has a gap of seven million units of affordable housing. Figure 2 shows the number of affordable and available rental units per 100 rental households at or below the poverty level or 30 percent of area median income (AMI) in each state. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, there is no metro area in which full-time workers earning the federal minimum wage can comfortably afford the costs of a typical two-bedroom rental unit (NLIHC 2020a).

Figure 2. . All states lack the numbers of affordable rental units needed to house all residents (Source: NLIHC)

The coronavirus pandemic illustrates the deadly effects of historical and contemporary policies and practices on housing opportunity as well as the heavy price Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities continue to pay as they suffer higher rates of infection, hospitalization, and death from COVID-19. Workers of color are more likely to be employed as "essential workers" in lower-paying jobs with fewer benefits such as paid sick leave. Meanwhile, an analysis by The Center for Public Integrity found that most of the eviction filings since March 2020 have occurred in minority and low-income neighborhoods (Kleiner, Rebala, and Yerardi 2020). These health and economic inequities have been linked to a long history of racist policies such as Jim Crow laws, racial zoning, redlining, and urban renewal, which has left a legacy of disinvestment and racial disparities in homeownership, income, and wealth. To realize the promise of equitable development, planning processes must address this legacy of injustice.

Traditionally, the practice of planning has focused on comprehensive land-use strategies, including creating and preserving affordable housing. But significant capital is needed to move from vision to reality, and too often planning and financing are organized separately.

One reason for this is that community investment is typically perceived as the purview of developers and finance professionals, not planners. However, through strategic partnerships with other community investment stakeholders, planners can help advance the deals and projects necessary to achieve more equitable housing outcomes.

Hospitals and Health Systems as Community Investors

The magnitude of our current housing crisis and the uncertainty of the post-COVID future require a shift in "business as usual." To produce housing affordable to middle- and low-income people and address deeply rooted racial inequities, planners need to identify and cultivate community investment stakeholders with the missions and motivations to support equitable development.

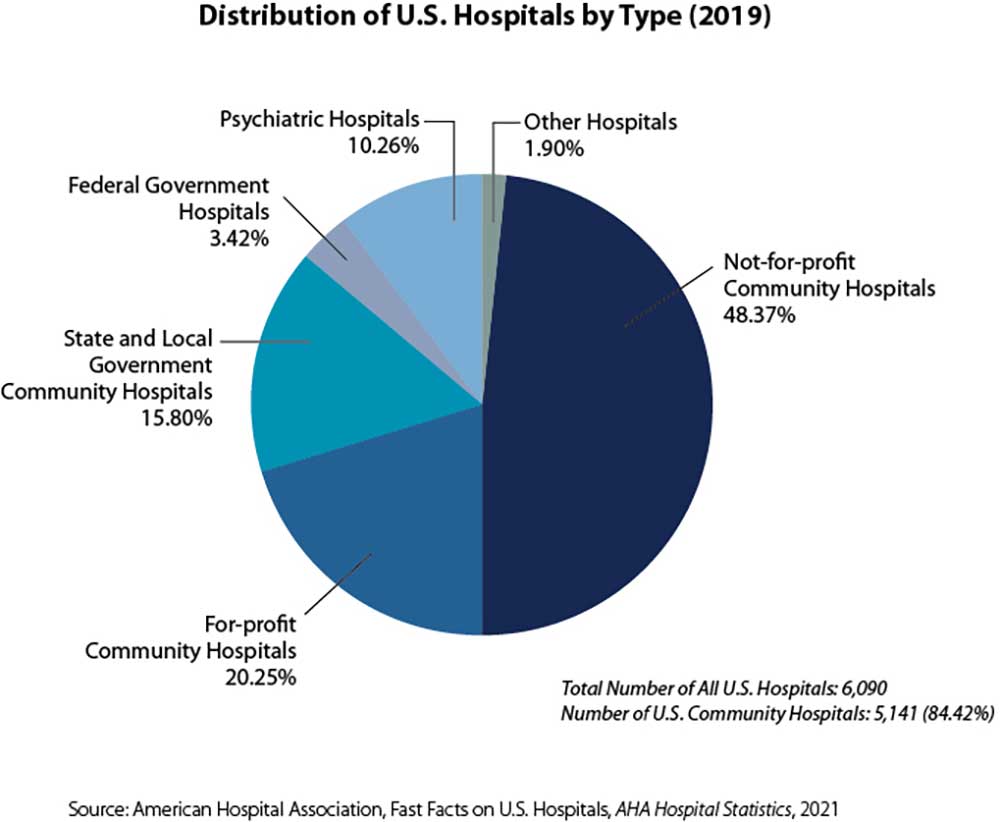

According to the American Hospital Association, there are more than 6,000 hospitals in the United States, including 5,198 community hospitals, of which 2,937 are not-for-profit, 1,296 are for-profit, and 965 are run by state and local governments (AHA 2021) (Figure 3). Though hospitals and health systems may not be traditional community investment actors, they have an interest in creating vibrant, healthy communities — and they have the resources to help do so. Research by the Democracy Collaborative finds that these institutions have an estimated $400 billion in investment assets that could be leveraged to advance equitable development goals (Zuckerman and Parker 2017).

Figure 3. Nearly half of all U.S. hospitals are not-for-profit community hospitals, which are leading the way in community investment approaches (Center for Community Investment)

Although any type of hospital can adopt a community investment approach, not-for-profit hospitals have been leading the way. Because of their tax-exempt status, nonprofit hospitals are legally required to serve their communities. This obligation is called community benefit. Additionally, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 requires not-for-profit hospitals to conduct a Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) every three years and to adopt a plan to address identified needs such as housing, jobs, education, food security, and health care access. Community investment is a natural fit for community benefit strategies to address health needs.

More than 50 percent of health outcomes are determined by the conditions where people live and the environments that surround them (County Health Rankings Model n.d.). A significant body of research demonstrates that safe, quality, affordable, stable housing supports positive health outcomes across the lifespan, while unsafe and unaffordable housing can deepen health inequities (Taylor 2018).

As our health care system begins to move from "volume to value" (rewarding good health outcomes rather than simply paying for procedures), health institutions are seeking strategies to advance health equity, improve health outcomes, and reduce health care spending. These range from reducing barriers to accessing care by providing medical services in locations like school-based clinics to investing in transforming the social determinants of health. For all the reasons noted above, many health institutions have focused on affordable housing.

Hospitals and health systems have an array of assets they can use to support the preservation and production of affordable housing. These assets include land, financial resources, purchasing power, expertise, relationships, and influence. Pioneering hospitals and health systems are exploring their community investment options, from investing in funds and projects to considering how hospital-owned land might be used to develop affordable housing, making them great potential partners for planners.

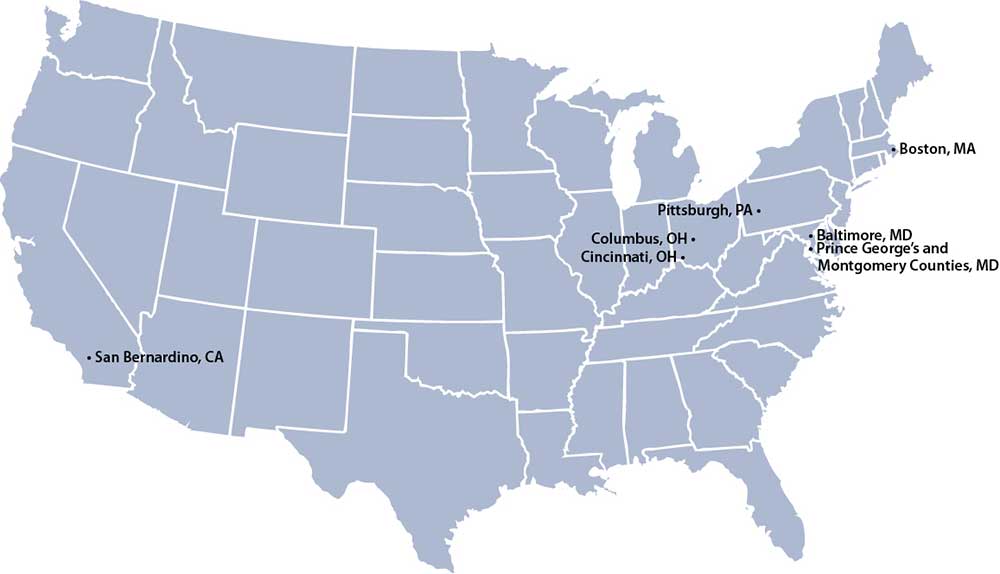

In early 2018, CCI, with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, created Accelerating Investments for Healthy Communities (AIHC), a cohort of six innovative nonprofit hospitals and health systems that are using their assets to invest in affordable housing. AIHC was designed to support participants at this leading edge of community investment practice in deepening and accelerating their investments in the communities they serve (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Communities served by the six AIHC nonprofit hospital and health system participants (Center for Community Investment)

Through AIHC, we have learned a lot about what motivates hospital investments. The conventional wisdom is that health institutions are motivated by economic drivers such as defined targets for return on investment; interested in approaches that target high-need, high-cost populations (e.g., chronically ill homeless people); and inclined to fund services rather than invest in long-term solutions like affordable homes.

AIHC participants have shown us that health institutions have additional motivations, including:

- Advancing mission. Almost all hospital mission statements focus on improving health. Institutions that adopt a community investment approach generally view health as more than overcoming disease. Understanding that "your ZIP code may be more important to your health than your genetic code" (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation 2013), they see improving the physical, social, and economic conditions in their communities as essential to fulfilling their missions. AIHC has seen such institutions subsidize housing for people with low incomes, invest in affordable housing developers and provide gap financing for housing deals, and even consider using their land for affordable housing, regardless of whether their patients and employees will directly benefit.

- Strengthening public-sector relationships. Health institutions depend on the public sector for many important approvals, from zoning variances and building permits to mergers and new services. If increasing affordable housing is a local government priority, then supporting housing deals and projects is an excellent way for hospitals to strengthen relationships with elected officials and agencies.

- Enhancing relationships with residents. By investing in a community-endorsed vision for affordable housing, hospitals and health systems can strengthen relationships with the communities they serve and build goodwill.

- Enhancing reputation and competitiveness. A health institution that seeks to attract and retain staff and patients has a vested interest in the health of its surrounding neighborhood. By investing in affordable housing, hospitals and health systems can make it more attractive for employees to live near the institution and ensure that the area around the hospital facility is vibrant and safe.

- Generating a financial return. As impact investors, health institutions have the opportunity to advance their mission while receiving a return on their investment, directly in the form of interest on loans and indirectly through savings and avoided costs. Returns can be recycled into future investments.

These diverse motivations have fueled growing hospital interest in housing. This in turn is creating shared interests between health institutions and planners and opportunities to overcome the racial, economic, and health disparities that are the target of equitable development. Unlocking the assets and expertise of these institutions can add new ideas, resources, and capacity to local community investment systems and help implement plans aimed at expanding housing opportunity.

Implementing Community Investment

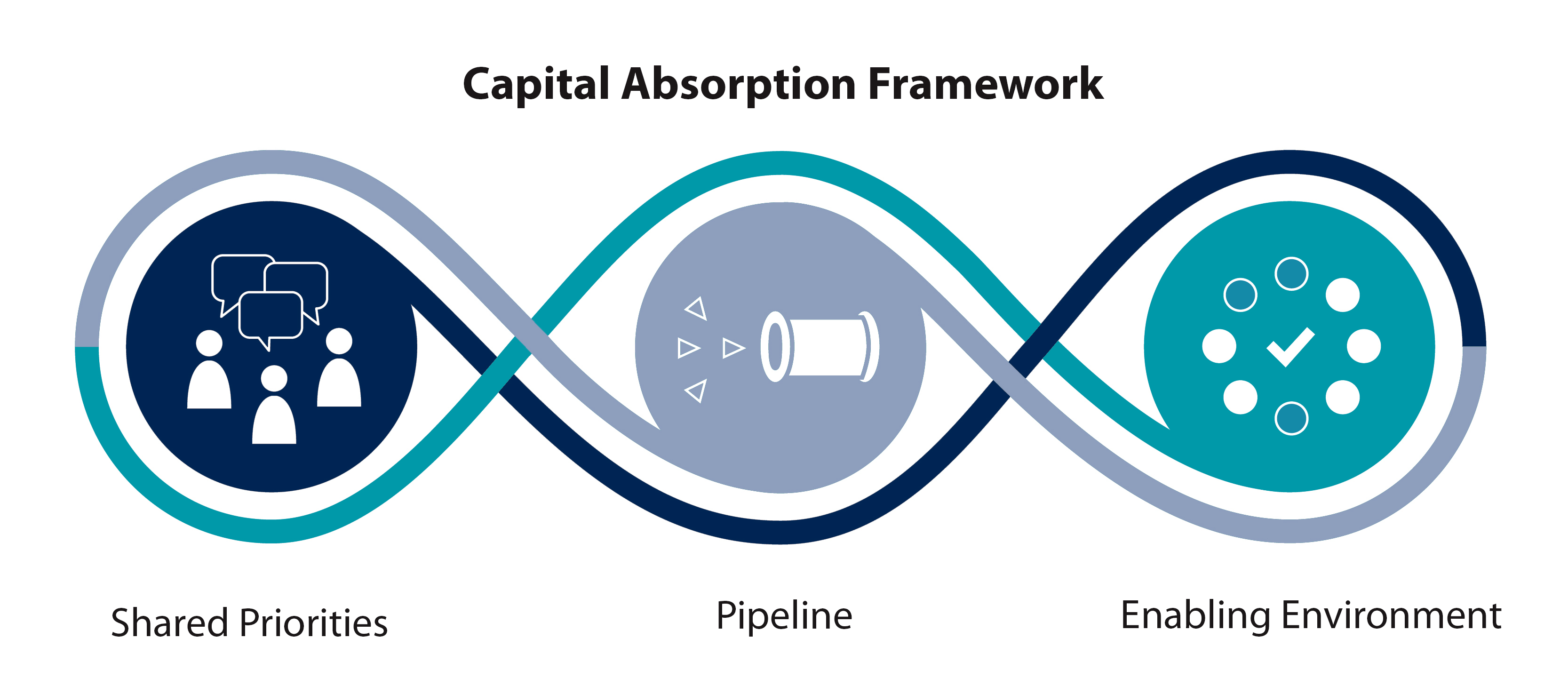

Even when eager investors are ready to provide funds, disinvested communities often lack the infrastructure to absorb investment capital successfully — that is, in ways that meet the needs of existing community residents. To overcome this challenge, CCI has created a framework to help community leaders build powerful and effective investment systems that support equitable development. This framework, called capital absorption (Figure 5), is based on three functions that enable a community to realize its development vision:

- Developing Shared Priorities: a community-endorsed vision broad enough to matter and specific enough to shape decisions

- Creating a Pipeline: a set of deals and projects that together will help achieve shared priorities

- Strengthening the Enabling Environment: the policies, practices, and relationships that impact how deals and projects happen

Figure 5. CCI's capital absorption framework (Center for Community Investment)

Planners exert significant influence in the design of neighborhoods, cities, and regions and ultimately on the conditions for community investment. Yet the idea of leveraging the planning process to build pipelines of projects for investment is relatively new. Planners can advance these capital absorption functions and help attract health institution investment in housing by:

- convening stakeholders to articulate community priorities for affordable housing;

- working with mission-oriented developers and the community to identify and prioritize a pipeline of housing deals; and

- creating a more supportive environment for accelerating the preservation and production of affordable housing by identifying opportunities to change policies and practices (such as syncing application deadlines for housing-related programs, creating density incentives, and expediting projects that advance shared priorities).

The following case studies illustrate how planners are working with hospitals and health systems to move affordable housing from vision to reality.

Nationwide Children's Hospital and the City of Columbus: Targeting Investments to Community Priorities

Over the years, the predominantly African American neighborhood of Linden in Columbus, Ohio, has seen declines in homeownership and increases in poverty. In 2017, Mayor Andrew J. Ginther announced a commitment to Linden as part of his focus on neighborhoods.

In response to the mayor's announcement, the Department of Neighborhoods, which oversees the city's community planning efforts, launched a resident-driven planning effort to better understand the community's needs, concerns, and visions for growth — their shared priorities. This process resulted in the creation of the Linden Community Plan: One Linden. One Linden outlines the desires residents expressed for improving the physical condition of housing, increasing housing options available for multiple income levels, and preventing the displacement of existing residents (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Linden residents want to improve the physical condition of homes in the neighborhood (Healthy Homes)

To help implement One Linden's recommendations, the Department of Neighborhoods recruited partners, including Nationwide Children's Hospital (NCH), an internationally recognized pediatric hospital and research institute headquartered in Columbus, which already had a community development initiative, Healthy Neighborhoods Healthy Families (HNHF). Launched in 2008, HNHF aims to improve community health outcomes by addressing affordable housing, education, health and wellness, community enrichment, and economic development. Through HNHF, NCH had already invested in the transformation of over 350 vacant and abandoned properties in the nearby South Side neighborhood into quality homes for local residents. NCH is now committing resources to advance the affordable housing targets listed in One Linden.

This partnership illustrates how the planning process can serve as a roadmap to direct hospital and health system investments to community priorities.

Kaiser Permanente and the Purple Line Corridor Coalition: Activating Policy to Support Affordable Housing

In 2017, construction commenced on the Purple Line, a 16-mile, 21-station light-rail transit corridor spanning Prince George's County and Montgomery County near Washington, D.C.

Knowing that large-scale transit investments can increase land values, raise housing costs, and displace existing residents, especially low-income families, the Purple Line Corridor Coalition, a public-private-community collaboration in Maryland, called for the preservation of 17,000 homes within one mile of the corridor and affordable to households earning $70,000 or less.

To help accomplish this goal, Prince George's County passed a Right of First Refusal (ROFR) policy in 2016 that gave the county's Department of Housing and Community Development the authority to buy multifamily rental facilities to preserve their affordability for low- to moderate-income households. The ROFR policy, however, went unused.

In 2017, Kaiser Permanente of the Mid-Atlantic joined CCI's AIHC initiative and created the Purple Line Corridor Coalition Housing Accelerator Team to accelerate progress on the housing preservation goals, in particular by exploring policy options for increasing affordable housing.

As a result of the Accelerator Team's advocacy, in 2019 Prince George's County significantly strengthened the ROFR process. The administrative regulation was revised to make the process more robust and easier to administer. As part of this effort, the county issued an RFP for mission-oriented developers to whom it can delegate its purchase right when it exercises the ROFR. Fifteen of 30 applicants were selected.

While the county has not yet fully exercised the ROFR, it has already used the process as a lever to protect residents in recent negotiations with developers over three properties. These properties have been repaired, they have not had rent hikes, and no residents have been displaced.

When hospitals and health systems leverage their influence in the policy sphere by adding their voice to existing coalitions or convening new collaborations, they can help shape the policies and practices that set the context for implementing plans, organizing deals, and protecting residents in affordable housing.

UPMC, UPMC Health Plan, and the Pittsburgh Urban Redevelopment Authority: Convening Partners to Respond to Affordable Housing Challenges

Through AIHC, UPMC, a Pittsburgh-based health care provider and Pennsylvania's largest nongovernmental employer, and UPMC Health Plan, the insurance arm of the health care institution, convened partners from many sectors to better understand local housing challenges and the role they could play.

One result is a fund for small landlords spearheaded by UPMC, UPMC Health Plan, and the city's Urban Redevelopment Authority. The Housing Opportunity Fund Small Landlord Fund will address the fact that some landlords who are willing to accept tenants with Section 8 vouchers have properties that cannot pass inspections, resulting in unused vouchers as potential tenants cannot find suitable homes. The fund is directly expanding the supply of available affordable housing units by providing landlords with loans for renovations and repairs, which will then qualify them to accept vouchers.

Partnerships that engage different perspectives, such as health and housing, can generate creative solutions that meet multiple needs.

Boston Medical Center: Comprehensive Plans Can Spur Community Investment

Housing a Changing City: Boston 2030, the city's comprehensive housing plan, articulates a vision for a Boston that supports "growth and prosperity for all" and outlines a plan to produce 53,000 new units of housing.

In 2016, Boston Medical Center (BMC) submitted plans for a new building, which triggered a Massachusetts requirement that health institutions commit five percent of the cost of new health care facilities to community health. Recognizing that access alone will not improve health outcomes, the requirement is designed to drive resources to the social determinants of health, including the built environment and housing. Health institutions are required to submit a plan to the state department of public health outlining how they will direct resources toward these social determinants.

After reviewing the housing plan, analyzing Boston's growing rates of homelessness and housing instability, and consulting with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Boston Alliance for Community Health, the Boston Public Health Commission, the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization, and local housing leaders, BMC decided to commit $6.5 million to expanding affordable housing opportunities in Boston's most underserved neighborhoods (Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan).

Along with grants to programs to address homelessness, BMC is investing in a housing fund and making $1.35 million of long-term, zero-percent interest loans available to affordable housing developers. This commitment will result in 300 new units affordable to individuals and families making between 30 and 80 percent of AMI and create a mechanism to recycle funds for future housing-related projects.

State and local policies can be critical drivers for hospital engagement in community investment, and community partners can help direct that engagement to where it can have the greatest impact.

Action Steps for Planners

Planners can support community investment in affordable housing by serving as conveners, data supports, advocates, and more. They can use the planning process and the capital absorption framework to set the stage for investments that implement their plans in the following ways.

Centering Racial Justice and Black Communities

Health institution investments in housing have the most potential to expand economic and social mobility and improve resident health outcomes when they are made with an intentional focus on equity.

Planners need to intentionally engage the Black community as part of the planning process. Given the harms caused to Black communities from the banking industry and federal, state, and local housing policies, such as redlining, it is particularly important to zero in on how to redress these injustices through equitable development practices. Without this intentional focus, investments risk exacerbating gentrification pressures and displacing lower-income residents. In AIHC, two participating health systems hired community engagement and strategy companies to help them connect with residents, understand the histories and root causes of health inequities, and listen to their visions for their communities.

Leveraging Community Health Needs Assessments

As noted above, nonprofit hospitals are required to conduct and publicize a CHNA every three years. In developing a CHNA, it is considered best practice to engage a broad array of community members and other stakeholders who can share their perspectives about local health challenges and opportunities.

CHNAs from local hospitals can be a valuable resource for planners. Hospitals are required by law to post their CHNAs on their websites, where planners can easily access them and find out who is responsible for them (generally staff in community benefit, community health, or population health departments). Planners can use CHNAs to better understand local housing needs, including identifying locations where poor housing is creating health hot spots and populations that are being underserved by current housing (such as seniors, families, or people experiencing homelessness). Paired with resident stories, as well as neighborhood plans and other planning documents, this data enables planners to make the case for where hospital investments might have the greatest impact on equitable development goals and community health needs.

Co-Creating Equitable Development Plans With Residents

Working with residents, especially those who are directly impacted by planning but rarely help to make the plan, can enable planners to more effectively identify possibilities for investment.

Asking the community how it would invest available resources can be a critical step in cultivating an inclusive planning process. When community members clearly articulate their needs and priorities, mission-oriented developers can work to translate those needs into investable projects.

Planners can work with local philanthropy and anchor institutions to convene and resource these stakeholders. One way to do this is by meeting people where they are, at the community locations they frequent and according to their schedules, rather than inviting them to special meetings that may be challenging to access or inconveniently timed. Engaging the community is critical for plans and investments to respond to the needs of residents.

Engaging Hospitals and Health Systems as Partners, Conveners, and Investors

Planners can use community plans and data to help focus community investment from health institutions, increasing the scale and potential impact of their investments.

Additionally, planners can work with these institutions to convene and forge partnerships with other investors, such as banks, local employers, foundations, and individuals, that may have an interest in investing in different types of affordable housing (e.g., family housing, permanent supportive housing, workforce housing, senior housing, employee housing).

Identifying an Enabling Environment Agenda to Support Affordable Housing Goals

Changes in policies and practices, funding flows, platforms, narratives, and relationships are often needed to create the conditions necessary to facilitate community investment.

Planners can partner with hospital and health system leaders to identify opportunities to accelerate investment in the preservation and creation of affordable homes through advocacy and policy change. Examples might include inclusionary zoning policies, housing trust funds, and density incentives, to name a few.

Health institutions can also leverage their influence to bring in new resources for equitable development. For instance, in June 2018, Dignity Health, now CommonSpirit, convened local elected officials, foundations, banks, Community Development Financial Institutions, developers, planners, and community-based organizations to discuss opportunities to revitalize San Bernardino, California. The California Strategic Growth Council (SGC), a cabinet-level committee responsible for coordinating the activities of state agencies to promote more equitable, sustainable, and resilient communities, attended and was inspired by the collaboration. SGC awarded San Bernardino $20 million through California's Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities program, which supported the creation of 180 new units of affordable housing in a development called Arrowhead Grove.

AIHC invited health institutions to convene local stakeholders to use a deal review to identify opportunities to advance policies and attract new resources. By asking the following questions, a deal review can help illuminate opportunities and challenges to improve the enabling environment:

- What policies and programs affected the deal?

- What were the challenges? What worked well?

- What sources of funding were or were not tapped? Why or why not?

- Who was involved in the deal?

- Where were there gaps in capacity, skills, or resources? What would it take to address these gaps?

It is through these conversations that health institutions, as well as planners, can learn about specific policies that they can advocate for to foster more equitable development.

Conclusion

Communities across the United States faced unprecedented challenges in 2020. A global pandemic that claimed the lives of nearly 300,000 Americans. An economic shutdown that left millions unemployed and many others a missed paycheck away from eviction or foreclosure. And the ongoing wrongs of racial injustice, a long-standing issue elevated in public consciousness by the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and the growing protest movement demanding justice for Black lives. All of these crises disproportionately affect the BIPOC communities who have long endured the effects of structural racism.

These challenges also represent critical issues for the planning field. As the nation shifts from crisis response to recovery, we must continue to focus on equitable development, an essential long-term strategy for supporting racial justice and creating more resilient communities. Far too often, however, equitable development plans have failed to achieve the transformative aspirations for inclusive growth heralded in their planning processes. Planners must improve upon their past efforts and embrace flexible, creative strategies to address these challenges to the health and well-being of their communities.

We stand at a critical moment in which our country has the opportunity for real change. Hospitals can play a significant role in advancing equitable development goals by leveraging their assets to invest in community needs, such as affordable housing. By engaging these community anchor institutions, planners can meaningfully advance their equitable development plans, meet the needs of the most marginalized communities, and ensure that all people have the housing they need to thrive. Using the information provided by this Memo, planners can help expand partnerships with health institutions across the country; advance investment in affordable housing, especially in low-income, BIPOC communities; and become more actively engaged in their local community investment systems.

About the Author

Alyia Gaskins, MPH, is a senior program officer at the Melville Charitable Trust. She was formerly the assistant director of networks and programs/health at the Center for Community Investment (CCI) at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. In this role, she led CCI's Accelerating Investments for Healthy Communities initiative. Gaskins holds master's degrees in public health and urban and regional planning from the University of Pittsburgh and Georgetown University, respectively.

The Center for Community Investment at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy works to ensure that all communities, especially those that have suffered from structural racism and policies that have left them economically and socially isolated, can unlock the capital they need to thrive.

The Lincoln Institute of Land Policy seeks to improve quality of life through the effective use, taxation, and stewardship of land. A nonprofit private operating foundation, the Lincoln Institute researches and recommends creative approaches to land as a solution to economic, social, and environmental challenges.

Acknowledgments

The work and insights of the hospitals and health systems participating in CCI's Accelerating Investments for Healthy Communities initiative were essential to the development of the ideas expressed in this Memo (and any errors are the author's). At the Center for Community Investment, Executive Director Robin Hacke and Director of Content Creation and Communications Rebecca Steinitz provided invaluable guidance and contributions throughout the writing process. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation provided support for Accelerating Investments for Healthy Communities and for the writing of this Memo, which was also supported by the Kresge Foundation.

References and Resources

American Hospital Association (AHA). 2021. Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals, 2021.

American Planning Association. 2019. Planning for Equity Policy Guide.

———. 2020. KnowledgeBase Collection: Social Equity.

Arnold, Andrea, Althea Ponsor, and Michael Bodaken. 2020. Preserving Affordable Homes for a More Equitable Future. Center for Community Investment at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and Stewards of Affordable Housing for the Future.

Boston, City of. 2014. Housing a Changing City: Boston 2030.

Community Economic Development Assistance Corporation (CEDAC). n.d. Housing Programs.

Center for Community Investment at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. n.d. Accelerating Investments for Healthy Communities.

———. 2019. "Defining Shared Priorities: The Capital Absorption Framework Part 1."

———.2019. "Analyzing, Executing, and Building a Pipeline: The Capital Absorption Framework Part 2."

———.2019. "Strengthening the Enabling Environment: The Capital Absorption Framework Part 3."

———. 2019. "Upstream All the Way: Why Pioneering Health Institutions are Investing Upstream to Improve Community Health."

———. 2020. "Deals as System Events: An Introduction to Deal Review."

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. n.d. Community Health Assessments & Health Improvement Plans.

Clemens, Austin, and Marcus Garvey. 2020. "Structural Racism and the Coronavirus Recession Highlight Why More and Better U.S. Data Need to Be Widely Disaggregated by Race and Ethnicity." September 24. Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

County Health Rankings and Roadmaps. n.d. What is Health?

Gaskins, Alyia, Rebecca Steinitz, and Robin Hacke. 2020. Investing in Community Health: A Toolkit for Hospitals. Catholic Health Association and Center for Community Investment at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Kleiner, Sarah, Pratheek Rebala, and Joe Yerardi. 2020. "Communities of Color Poised to Lose Their Homes As Eviction Moratoriums Lift." Coronavirus and Inequality, July 22. Center for Public Integrity.

Massachusetts Department of Public Health. n.d. Determination of Need.

National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC). 2020a. Out of Reach 2020.

———. 2020b. The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Rental Homes.

Nationwide Children's. n.d. Healthy Neighborhoods Healthy Families.

Neighborhood Design Center. 2018. One Linden Community Plan.

Prince George's County, Maryland. 2015. Right of First Refusal Regulations.

Purple Line Corridor Coalition. n.d. Housing Accelerator Action Team.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2013. Improving the Health of All Americans by Focusing on Communities.

Taylor, Lauren. 2018. "Housing and Health: An Overview of the Literature." Health Affairs Policy Brief, June 7.

Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh. 2020. Housing Opportunity Fund Small Landlord Fund.

Zuckerman, David, and Parker, Katie. 2017. Place-Based Investing: Creating Sustainable Returns and Strong Communities. Democracy Collaborative.

PAS Memo is a bimonthly online publication of APA's Planning Advisory Service. Joel Albizo, FASAE, CAE, Chief Executive Officer; Petra Hurtado, PhD, Research Director; Ann F. Dillemuth, AICP, PAS Editor. Learn more at planning.org/pas.

©2021 American Planning Association and Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without permission in writing from APA. PAS Memo (ISSN 2169-1908) is published by the American Planning Association, 205 N. Michigan Ave., Suite 1200, Chicago, IL 60601-5927; planning.org.