Standards for Outdoor Recreational Areas

PAS Report 194

Historic PAS Report Series

Welcome to the American Planning Association's historical archive of PAS Reports from the 1950s and 1960s, offering glimpses into planning issues of yesteryear. Use the search above to find current APA content on planning topics and trends of today.

More From APA

Interested in Parks and Recreation? You might also like:

Alternatives for Determining Parks and Recreation Level of Service

This issue of PAS Memo looks at determining appropriate level of service (LOS) standards for parks and recreation facilities within a community.

|

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLANNING OFFICIALS 1313 EAST 60TH STREET — CHICAGO 37 ILLINOIS |

|

| Information Report No. 194 | January 1965 |

Standards for Outdoor Recreational Areas

Download original report (pdf)

Prepared by John Moeller

Recreation and recreational standards have long been the subject of much discussion and controversy, extending so far as to question the value of standards as a measure of our recreational needs. This report hopefully will indicate that standards are necessary, not to the extent that they become hard and fast rules, but rather as a point from which one may begin.

It is not easy to define whether or not an area is "adequate," yet recreation specialists have come up with certain rough rules which are often used; one standard, for example, is that a city should have one acre of city park or playground per 100 population, plus another acre of large city or regional park on the outskirts of the city for more extensive types of recreational use. Even this amount of recreational space is not adequate unless the separate tracts are located according to need, and unless they are well planned, well developed, and well managed.

As far back as 1914 Charles Downing Lay, at that time landscape architect for the New York State Department of Parks, estimated the park needs of a city of 100,000 people to be:

| Recreational Uses | Area |

| Reservations | 700 acres |

| 1 large city park | 400 acres |

| 10 neighborhood parks | 250 acres |

| 50 playgrounds | 100 acres |

| Gardens and squares | 50 acres |

| Total | 1,500 acres |

He assumed that 12-1/2 per cent of the total area of the city should be devoted to parks. This meant that a city of 12,000 acres should have 1,500 acres of parks. For a city of 100,000 it meant an average population density of 8-1/3 persons per acre of city and an allowance of one acre of park space to 66-2/3 people.

In 1940, about one-quarter of all cities having park facilities met the standard of one acre per 100 population; some cities exceeded this standard considerably. Since 1940, the relationship between park and recreation area and total population has been a less happy one. Recreational area within the legal boundaries of the larger cities has expanded as population has grown, but, when the population of the surrounding suburbs has been added to that of the central city, the available park area has lagged seriously. The suburbs of a great many urban areas have failed to add park land to meet their own needs, and have tried to rely on the older parks of the central city. In 1956, the total area of the city and county parks was about three-quarter million acres; an adequate area by the above standards would have been two million acres.2

It has been suggested, however, that the general rule be modified, especially for densely populated cities. In many cases, it is economically impossible to attain such standards. It has been suggested in a report, Proposed Standards for Recreational Facilities, prepared by the Detroit Metropolitan Area Planning Commission (September 1959), that one acre per 200 population is a reasonable standard in cities with populations over 500,000, and perhaps one acre per 300 population for cities over a million inhabitants.

It should be pointed out that developing recreational facilities on the fringe of the city would help meet the recognized deficiency in the larger cities. This variation from the general standard has been adopted in Cleveland, for example, where the city planning commission has sought a standard of one acre per 200 population.

While most cities have recognized the standard of one acre of recreation land per 100 population, there has been much diversity of opinion concerning total open space requirements. Attempts have been made to establish the percentage of recreation space needed in relation to the area of the city. It has been stated that at least one-tenth of the city's acreage should be used for recreation. This type of standard cannot be completely satisfactory, however, since it does not take into consideration the population density. No rigid formula can be prescribed; all specific standards and recommendations are subject to variations, conditions, and peculiarities of the area surrounding the recreational facility.

Recreational standards are affected by the cultural background, age, and socio-economic status of the population, and these factors should be carefully studied to determine whether modification of any set of recommended standards is desirable. Standards should never be blindly adopted without considering modifications since they are predicated on a theoretically typical city that does not exist. The standards in this report should be taken as a point of departure and, as such, they can offer a basis for the intelligent development of local plans. Standards also need to be appraised from time to time, with the idea of adjusting them whenever changing conditions make modifications necessary. The investment in recreation facilities can be, and has been, wasted because local customs and preferences were not given sufficient consideration.

To a limited extent, the type of recreation facilities to be provided will depend upon the degree to which community needs may be met by private facilities or within residences. For example, in many suburban areas, the size of residential lots and living areas is such that there is little need for a neighborhood playlot. On the other hand, in a low-income, high-population density neighborhood where living space is at a premium, playlots become extremely important.

There is general agreement among city planners and recreation authorities that 30 to 50 per cent of the total park and recreation land of a community should be set aside for active recreation.3 Based on the recommended standard of one acre per 100 population, it has also been stated that from 25 to 50 per cent of the total space should be developed for neighborhood use, with the remaining acreage in community, city-wide, or regional facilities.

In comparing recreation standards, it should be kept in mind that those suggested by the National Recreation Association are probably most applicable to smaller cities, rather than to the more densely populated urban centers. As shown in the samples given in Table 1, published standards for municipal recreation have ranged from four acres per 1,000 population to the 10 acres per 1,000 suggested by the NRA.

Table 1

Total Area for City Recreation — Comparative Chart

| Standards in Acres Per 1,000 Population | ||||

| Type of Recreation Area | N.R.A. | Seattle, Washington | Royal Oak, Michiganc | Detroit, Michiganf |

| (Active rec.) | ||||

| Playgrounds | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.57 | 0.5 |

| Playfields | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.31 | 1.0 |

| (Total active rec.) | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.88 | 1.5 |

| (Passive rec.) | ||||

| Minor parks | 2.50 | 1.25 | 1.54d | . . .g |

| Major parks | 5.00 | 2.50 | 5.74e | 2.6 |

| (Total passive rec.) | 7.50 | 3.75 | 7.28 | 2.7 |

| All types of municipal recreation | 10.00a | 6.25b | 10.16a | 4.1 |

Source — Report on Recreation Standards, 1954; Detroit Metropolitan Area Regional Planning Commission.

a. In addition to the 10 acres of recreation per 1,000 of the population of the municipality, there should be, for each 1,000 people in the region, 10 acres of park land in stream valley parks and parkways, large scenic parks and forest preserves under municipal, county, state, federal or other authorities.

b. In addition to the recreation acreage within the urban area there should be at least 10 acres of reservation or recreational area left in their natural state for each 1,000 persons.

c. This recreation study was completed in April of 1954 by the NRA. Figures based on the ultimate population of Royal Oak as being 85,000.

d. Parks of 20 acres or less in size.

e. Parks of over 20 acres in size.

f. The Detroit City Plan Commission in a master plan report published in 1947 gave the proposed recreation in the city of Detroit based on the population of 1,800,000.

g. Did not have figure for minor parks. Not included, however, is 0.1 acres per 1,000 population which includes greenbelt, park department nurseries, and yards, and barns for equipment located in parks.

In long-range developments, priority should be given to planning recreation areas for neighborhood use in connection with elementary schools. Special attention should be given to subdivisions at the time they are reviewed by the planning agency in order to guarantee that adequate space is set aside to serve the neighborhood park and recreation needs. If the opportunity is missed at this point it is probably lost forever.

The modern municipal park and recreation system is composed of properties that differ in function, size, location, service area, and development. Generally, these recreation areas are divided into three groups based on the areas that they serve: those that serve one neighborhood, which would include playlots, playgrounds, and neighborhood parks; those which serve several neighborhoods or the so-called "community" in the large city, which would take in playfields and community parks; and those that serve a very large section of the city, or even the entire metropolitan area. These latter include parkways, major parks, reservations, regional parks, and highly specialized facilities, rather than multiple use developments.

Because of the vast size of the subject, emphasis in this report is given to standards for recreational areas — minimum and maximum space requirements, location of recreational facilities and size of population served, the types of facilities required for various recreational areas, and what age groups can be expected to be served by these facilities. There has been no attempt to include standards of design for outdoor recreational facilities, though it is recognized that such standards are of the utmost importance. For this reason, sources for design standards have been included in the bibliography. Also, the scope of this report has not permitted consideration of sociological factors, such as the economic and cultural composition of the population to be served.

The first part of this report deals with the various areas to be served; the second part includes standards for a few specialized facilities that might be located in various recreational areas.

Neighborhood Facilities

A neighborhood is normally considered to be an area served by one elementary school. Its population varies from 2,000 to 10,000, averaging 6,000. Just as standards for elementary school location call for the school to be within walking distance of the homes it serves, so should neighborhood parks and playgrounds be within walking distance of the families in the neighborhood. It is desirable to locate parks and playgrounds adjacent to elementary schools, to make possible the joint use of school, park, and playground areas for the pupils and the general community.

The following discussion of neighborhood recreational facilities, together with the accompanying tables describe and summarize standards that have been published by several different agencies. It is emphasized again that there are no absolutes in recreation criteria. Although these standards are usually declared to be the "minimum," it is certain that the "minimum" will never be reached by all cities. Furthermore, in some communities, the "minimum" will be much more than is actually needed, while in other cities, the recommended "minimum" will be pitifully inadequate. These observations on the standards apply not only to those suggested for neighborhood facilities, but to all other standards covered in this report.

Playlot

Playlots (Table 2) are small areas intended for children of pre-school age. They are essentially a substitute for the individual backyard and are normally provided in high population density areas or as a part of a large-scale housing development. Such facilities are provided by the municipality only occasionally in an underprivileged neighborhood where backyard play opportunities are not available. In most cities the separate playlot is not considered an essential part of the municipal recreation system, and provision for such areas is left to private agencies or housing authorities. It is quite common, however, to include a playlot area as part of a neighborhood playground. The facilities of a playlot should be simple and safe and include the following: swings (low, regular), slides (low), sand box, mountain climber (low), play sculptures, one or more play houses, open area for free play, a shelter with benches for mothers, space for baby carriages, small wading pool or spray pool, concrete walk and paved area for wheeled toys, and with a low fence around the entire area.

Table 2

Playlot

| Min. Area Necessary | Desired Size For Best Results | Age Group Served | Population Served | Service Radius | Average Space per Child | |

| National Recreation Association | 2,400 to 5,000 sq. ft. | 300 to 800 | 1 block or 1/8 mile | 50 to 60 sq. ft. | ||

| Local Planning Admin. | 2,000 to 5,000 sq. ft. | 300 to 700 | 1 block or less | |||

| American Public Health Association | Min: 1,500 sq. ft. Max: 5,000 sq. ft. |

3,750 sq. ft. | Pre-school | 75 children or less | 300 to 400' of every house and cross no streets | 50 sq. ft. 40 sq. ft. |

| Recreation & The Town Plan Conn. Develop. Comm'n.* | 1/8 acre or 2,000 sq. ft. | 1/8 to 1/4 acre or 5,000 to 10,000 sq. ft. | Pre-school, under 6 | 250 to 700 | 1/4 miles | |

| Rockland Co. N.Y. Recreation Study | Max: 5,000 sq. ft. | Pre-school | 1/8 mile | 50 sq. ft. |

*Also recommended is 0.3 acre as minimum per 1,000 population.

Playground

The neighborhood playground (Table 3) is an area which serves primarily the needs of the five–to 12-year age group, but may also afford limited facilities to the entire neighborhood. The playground is the chief center of outdoor play for children, with limited opportunities for recreation for youths and adults. As mentioned previously, a section of the playground may be developed as a playlot. Hopefully, it becomes a center where the people of the neighborhood can find recreation and relaxation with family, neighbors and friends.

Table 3

Playground

| Min. Acreage Per 1,000 Pop. | Min. Area | Area for Best Results | Age Group Served | Population Served | Service Radius | Location | |

| Local Planning Admin. | 1.25 | Min. 3 acres; Max. 7 acres | 5 acres | All ages but mostly 5-15 years | 3,000 to 5,000; ideal 4,000 to 5,000 | High density: 1/4 mile Low density: 1/2 mile |

Next to an elementary school and also be central in the neighborhood |

| Rockland Co., N.Y. Medium density High density |

5.0 5.3 |

10 acres 8 acres |

5-12 years 5-12 years |

Min. 2,000 Min. 1,500 |

3/4 mile 1/4 mile |

||

| Athletic Institute | 2 or more acres | 5 acres | 5-10 years | 1/4 to 1/2 mile | In the neighborhood. If connected to a school more area needed | ||

| American Public Health Association | 2.75 for 1,000 pop; 6.00 for 5,000 pop. | 2.75 acres | 1,000 to 5,000 |

A basic goal of the neighborhood playground is flexibility in design to meet varied short-term active and passive activities for children. The playground is the basic unit in a city's recreation system. Desirable features in the neighborhood playground will include (see Fig. 1 for playground layout): playlot for pre-school children; apparatus area for older children; open space for informal games and play activities; paved area for older children; open space for informal games and play activities; paved area for court games; field area for games; shade area for story telling; shelter house and drinking fountains; wading or spray pool; shaded passive area for older people; landscaping, with perhaps a small garden and picnic area.

The Rockland County Recreation Study has listed space requirements for a playground which can be found in the Appendix A.

Figure 1

Proposed design for typical neighborhood playground.

Source: Long Range Recreation Plan, City of Baltimore, Maryland. Prepared by The National Recreation Association, 1943.

Junior Playground

In some neighborhoods, because of unusual conditions, it will be practically impossible, short of a drastic redevelopment project, to provide a standard children's playground of the size suggested. If the maximum space which can be made available is less than two-thirds of the desired minimum standard areas suggested in Table 3, it has been suggested that a "junior" playground be provided.4 A junior playground will include many, but not all, of the same types of areas as the normal playground. Because of the size of these areas, a smaller number of people of various ages will be served. Under such conditions the available space may best be planned for children up to 11 years of age who require much less space than older children.

Figure 2

Study for development of junior playground.

Source: Long Range Recreation Plan, Town of Kearny, New Jersey. Prepared by The National Recreation Association, June 1942.

A wading pool would normally be omitted from this type of playground, but a spray pool or shower device is desirable. The landscaped area for adults may be omitted. If it is decided that the playground should be restricted to children under 11, definite plans must be made to care for the play needs of the older children within a reasonable walking distance. The NRA has stated that a playground of one acre restricted to children under the age of 11 may serve the needs of a neighborhood containing 300 children between the ages of five and 11.5

The Athletic Institute proposed a minimum site of one acre for a junior playground,6 but suggested that two or more acres be acquired where possible to provide a park-like setting. The Institute also states that a utility or shelter house is needed on the junior playground. Most park maintenance authorities believe, however, that a two-acre playground is the very minimum that can be economically maintained.

Neighborhood Park

The purpose of the neighborhood park is to provide an attractive neighborhood setting and a place for passive recreation for people of all ages. The area should have trees to give protection from the sun during the summer.

The type of neighborhood influences to a great extent the particular need for neighborhood park space in relation to playground acreage (Table 4). Population density is a significant factor in determining needed neighborhood park space. Several studies recommend that more space should be provided in multifamily, high population density neighborhoods and in areas with a large percentage of elderly adults than will be needed in single-family neighborhoods.

Table 4

Neighborhood Park

| Min. Acreage Per 1,000 Pop. | Min. Area | Area for Best Results | Age Group Served | Population Served | Service Radius | Min. Area Necessary | |

| A.P.H.A. One or two family Multifamily |

3.5 for 5,000 pop.; 1.5 for 1,000 6.0 for 5,000 pop.; 2 for 1,000 pop. |

1.5 to 3.5 2.0 to 6.0 |

1,000 to 5,000 |

1 1/2 to 2 acres |

|||

| National Recreation Assoc. | 1 acre | Not applicable 1/2 to 25 range | All | 4,000 to 6,000 | Central | Easy walking distance (1/2 mile) | |

| Local Planning Admin. | 1 acre | 1/2 to 2 when part of playground; 7 if by itself | All | 4,000 to 7,000 | Central; in connection with playground | Easy walking distance (1/2 mile) | |

| Athletic Institute | 10 | All | Central; small if connected to a school | Walking distance | |||

| Recreation & the Town Plan (Conn.) | 1 acre | Varies with population density | All | Central; small if connected to a school | Walking distance | 7 acres if not adjoining playground or field |

Desirable features for the neighborhood park include: open lawn area; trees and shrubbery; tables and benches for quiet games; walks and shade areas; ornamental pool, fountain, or sundial; play apparatus for children (optional); shelter building with game room, storage, and toilet facilities; multi-purpose, all weather court area; spray basin or wading pool.

Community Facilities

Between the neighborhood facility and the major park which serves the entire city, there should be a large recreation area (20 to 25 acres) to serve several neighborhoods. This facility should be centrally located for the area it serves and, when possible, adjacent to a school. The two most common types of community facilities are the playfield and the community park, which in some cities have been combined to form a playfield-park.

Playfield

The playfield provides varied forms of recreational activity for young people and adults, although a section may be developed as a children's playground (Table 5). The playfield provides for popular forms of recreation that require more space than would be available in the playground, The playfield is a multi-purpose area to provide activities and facilities for all age groups and to serve as a recreation center for several neighborhoods. A portion of a playfield will be developed as an athletic field for highly organized team sports.

Table 5

Playfield

| Min. Acreage Per 1,000 Pop. | Desired Size for Best Results | Age Group Served | Population Served | Location | Service Radius | Parking | |

| National Recreation Association | 1.25 acres | 20 to 25 acres | Young people and adults | Not more than 20,000 | Central 3 to 5 neighborhoods preferred adjoining a school | 1 mile or less from every home (varies with pop. Density in some cases) | Parking area required |

| Local Planning Admin. | 1.25 acres | 18 to 32 acres | 15 years and over | 15,000 to 25,000 | Central adjoining a school convenient to local transportation | 1/2 to 1 mile travel distance or 20 minutes by car or trans. | 1 to 2 acres |

| Recreation & the Town Plan (Conn.) | 1.3 acres | 12 to 20 acres | 15 to 24 years and family groups | Central 4 to 5 neighborhoods adjacent to Jr. or Sr. high schools | 1/2 to 1 mile travel distance | ||

| Rockland Co. (N.Y.) | 20 acres super playground | Adults and children over 12 years | 9,000 min. | In connection with a school site when possible | 1 1/2 miles from playfield | Parking should be provided | |

| Detroit | 2 1/2 acres playfield parks | 20 acres adequate shape for major activities | Older children & adults | Central and when possible near or adjoining a school site | 1 to 1 1/2 miles in a low density area | Parking should be provided |

The playfield should provide most of the following features: area for game courts, including tennis, volleyball, handball, basketball, horse shoes, shuffleboard, and other games; separate sports fields for men and women for such games as softball, baseball, football, and soccer; open turfed lawn including picnic areas, landscaped park, and children's play areas. There may also be a fieldhouse, running tract, and space for field events; children's playground; outdoor swimming pool; and center for day camping. The area should be lighted for night use. There must be adequate off-street parking areas.

Minimum and maximum space requirements for a typical playfield can be found in Appendix B.

Community Park

While there is some variation in the standards recommended for the facilities described thus far, there is also a great deal of agreement. A community park, however, seems not to be a very clear concept. It apparently caters somewhat less to active sports than does the playfield. It seems that perhaps the term "community park" is actually no more than an answer to the question: "What would you call a parcel of municipally-owned land 20 to 25 acres in size?"

The community park (Table 6) is a park facility that is large enough to serve several neighborhoods. It is planned primarily to serve young people and adults. Because it does serve several neighborhoods, it should be accessible by public transportation, and it must have ample off-street parking facilities.

Table 6

Community Park

| Min. Acreage Per 1,000 Pop. | Desired Size for Best Results | Age Group Served | Population Served | Service Radius | Parking | |

| National Recreation Association | Few require such | 25 to 50 acres min. 25 acres | 20,000 to 40,000 | 1/2 to 2 miles 1 mile most frequent | ||

Guide for Planning Recreation Parks in California |

Adjoining School | |||||

| 1 acre or more | 20.06 acres | Young people and adults | 5,000 to 25,000 depending upon the region | 1 to 1 1/2 miles usually served by transportation | 1 acres | |

| Separate | ||||||

| 1 acre or more | 32.75 acres | Young people and adults | 5,000 to 25,000 depending upon the region | 1 to 1 1/2 miles usually served by transportation | 1 1/2 acres | |

| National Council on School House Construction | Add 1 acre per 100 pupils of predicted ultimate enrollment | Jr. high 20 acres Sr. high 30 acres |

Jr. high 1 mile Sr. high 3 miles |

|||

| Vancouver | 25 acres | All ages | 10,000 to 20,000 | 1 mile | ||

The California Committee on Planning has recommended facilities for the community park, which are given in Appendix C.

City-Wide Recreational Areas

In addition to facilities that serve the neighborhood and community, there are those that serve a still larger section of the city, or the whole city. Included are the large parks, golf courses, athletic fields, parkways, and camp sites. Standards are difficult to establish for these facilities. See Appendix D for a sample of suggested space standards covering all city-wide recreation facilities to service a population of 100,000.

Major Parks

Major parks (Table 7) are designed and developed for diversified use by large numbers of people. Because of their area, they will contain facilities that cannot be accommodated in the neighborhood or community park. They give the city dweller contact with nature and a pleasant environment in which he can engage in a variety of recreational activities.

Table 7

Major Parks

| Min. Acreage Per 1,000 Pop. | Desired Size for Best Results | Age Group Served | Population Served | Service Radius | Location | |

| National Recreation Association | 2.5 acres | 100 acres | All | 50,000 | 30 minute maximum | Readily accessible to the whole city |

| Local Planning Administration | 2.5 to 4 acres | 100 acres | All | 30 to 60 minutes travel distance accessible to public transit | One in every major section of the city | |

| Detroit | Minimum 3 acres | 200 to 300 acres | ||||

| Athletic Institute | 100 acres or more | All | 50,000 | Not more than 2 miles from any neighborhood | Central or fringe location | |

| Recreation and the Town Plan Conn. Development Commission | 3 acres | 75 acres, city 150 acres, regional |

All | 1/2 to 1 1/2 hours travel distance | Close to urban area for all day outings |

With the increase in the purchase and reservation of lands for "regional" parks outside the city limits, a greater proportion of the large in-city parks are being turned into active recreation areas.

Desirable features for the large city parks include: natural landscape and landscaping; large picnic areas; athletic fields; playground; numerous play areas; archery range; nature trails; bandstand; comfort stations; winter sports center; day camps; off-street parking. Additional specialized features include: golf course, bridle paths, boating and swimming facilities, zoo, botanical garden, museum, and outdoor theater.

Reservations

Reservations (Table 8) and regional parks serve as greenbelts within urban areas. "Reservation" is a term sometimes applied to large outlying areas. It is not easily distinguished from a regional park except perhaps that the reservation is less fully developed. The reservation should provide facilities only for those activities that are primarily incidental to the maximum enjoyment of nature and the natural scenery. Such activities would include: overnight and long-term camping facilities; picnic areas; swimming facilities; fishing; boating; winter sports.

Table 8

Reservations

| Desired Size Per 1,000 Pop. | Age Group | Location | Service Radius | Population Served | |

| National Recreation Association | 1,000 to 5,000 acres | All | Mostly located outside the city | 60 minutes away | |

| Local Planning Admin. | 500 to several thousand acres | All | Preferred outside urban area | Flexible | Entire urban area |

Play equipment and sports fields are not appropriate here except for minimum facilities near camping and picnic centers. Large sections of the reservation should be reserved for hiking and bridle trails. The location of buildings and refreshment facilities should be selective and only at widely spaced major activity centers.

The reservation is often owned by a county, state, or special district, but it may be owned by the city even though it is outside the corporate limits. The concept of large parks and open space to counteract urban pressure and to preserve scenic areas does not lend itself easily to standards. If there is any single standard for a regional park, it is that it must be large. Any tract smaller than one square mile could hardly qualify for the term "regional" — five to 10 square miles or more is not too large.

The National Recreation Association recommends a site anywhere from several hundred to 1,000 and up to 5,000 acres as a desirable size. These areas are normally located outside the city boundaries and should not be more than 60 driving minutes from the city.

The regional park will have large areas of forest reservation, with unusual scenic character if possible. It normally serves one or more cities, or part of a large metropolitan area.

The regional park has three functions: to preserve a portion of the natural landscape, to supplement the recreational facilities of the urban area, and to act as a greenbelt in separating cities in a large metropolitan region.

Both reservations and regional parks have extensive facilities for all-day and weekend outings for the entire family and should be within a reasonable driving distance. Facilities will include boating, fishing, and camping sites; natural wooded areas or wilderness; trails for horseback riding, hiking, and nature study; and large beaches. They should be accessible by highway, have facilities and space sufficient for large-scale development, and have an administrative agency operating them. Normally not included in such a park would be game or wild life areas, which should be separately established away from recreational areas; nor would these parks provide facilities for team or other organized sports. The reservation as well as the regional park will serve all ages and the entire urban area.

Parkways

The parkway is essentially an elongated park with a road extending its entire length. It is often located on a ridge, in the valley of a stream, on a palisade overlooking a stream, or along a lake or ocean frontage. A parkway may serve to connect large units in a park system or to provide a pleasant means of travel through the city and the outlying region. This type of facility is found principally in large metropolitan areas.

The parkway is basically a recreation facility, not a transportation facility. Although at times it may carry a fairly heavy traffic load, as on the first pleasant Sunday in spring, the parkway should be consciously designed to avoid its being a convenient and direct route between centers of urban activity. A parkway should not be allowed to become an expressway. Its principal attribute should be beauty, not efficiency.

The report, Regional Recreation Areas Plan (1960), prepared by the Regional Planning Commission and the Parks and Recreation Department of Los Angeles County states:

Even though Los Angeles County contains one of the most mobile populations in the world through the use of private automobiles, there are few adequate examples of existing parkways in the County. The scenic drives in Griffith and Elysian Parks are the only scenic drives in the non-mountainous portions of the County which can be classified as Parkways. The Arroyo Seco Parkway (renamed the Pasadena Freeway) has been frequently cited as a parkway example, but this Plan does not consider it a parkway because it carries high speed traffic and the park development is separated from the freeway by a right-of-way fence.

The National Recreation Association recommends the minimum width for a parkway as 200 feet,9 but suggests that it should be much wider if possible. The park area may be used for bicycling, hiking, horseback riding, or picnicking.

Specialized Recreational Areas

Certain areas and facilities are highly specialized. They may be developed separately and on special tracts of land, or they may be integrated into parks and other recreational areas. More and more, these facilities are providing for many of the major recreational activities, and provision for such activities cannot be neglected. In the past few years, there has been a tendency to acquire special sites for these facilities, rather than trying to combine them with the standard recreational area facilities. Standards have been developed for some of the specialized facilities, but for others no particular site size can be specified.

Athletic field or Stadium

This specialized type of facility (Table 9) is intended primarily for highly organized games and sports which attract less than 10,000 spectators.

Table 9

Athletic field or Stadium*

| Min. Area Required for an Athletic Field | Location | Service Radius | Min. Area Required for A Small Stadium | |

| National Recreation Association | 10 acres | At a high school site or as a portion of a playfield | Neighborhood or community level — convenient to transportation | 20 acres |

| Streator, Ill. | 10–20 acres | Usually located at a high school | 10–20 acres | |

| Baltimore, Md. | 5 acres or more | High school site or at neighborhood playfield | 5 acres or more |

*The small stadium, with a seating capacity of 3,000 to 10,000, is not for city-wide use except in small cities where the facility may serve the entire population.

Stadia are permanent outdoor seating structures with their areas intended for observing athletic and other activities sponsored by schools or municipalities. The small stadium — seating from approximately 3,000 to about 10,000 — usually consists of a single permanent seating structure that may extend down one side of a playing field or it may consist of two such stands. Two stands on opposite sides of the field, seating 3,000 each, will cost considerably more and provide fewer desirable seats than a single stadium on one side, which will seat twice the number.10 The stadium should be planned to meet the needs of the community and to lend itself to evolution into a horseshoe or a bowl if the demand arises. The Athletic Institute11 states that:

The functional planning of stadia has purposely been directed chiefly at the larger and more inclusive and involved structures.

However, the following basic considerations should guide plans for smaller structures:

All the principals of functional planning suggested for larger stadia are applicable to smaller structures; the specifics apply in number, to the degree and in a proportion dictated by the capacity, location, uses and future possibilities of the plant.

Planning for a small stadium should be exposed to the same reasoning and measurement of values as that to which the planning of a colossal structure is subjected.

The permanent seating stands can be much more than tiers of seats. Underneath is very valuable space. It should be utilized for storage, activities and accessory needs.

The smallness of a so-called stadium does not excuse planning which ignores efficient and economical maintenance and operation, wastes space, slights spectator convenience and enjoyment, defeats maximum participant performance, abuses public relations and disregards future growth and demands. Small stadia are the seeds of larger ones.

In planning and construction, due consideration should be given to the use of the stadium for various events of wide interest, such as athletic contests, patriotic observances, graduation ceremonies, parades, drills, band concerts, and special exhibitions.

Features that should be included in a stadium are: jumping and vaulting pit; track (one-quarter mile); football field; baseball field; soccer field; tennis courts; pressbox; toilet facilities; storage facilities (under grandstand); drinking fountains; locker and shower facilities; and flood lights. The entire area should be enclosed by a wall or fence.

A very large stadium for professional sports does not really come within the scope of this report. Many problems relating to the design and construction of such a stadium in a given locality are highly technical and require expert advice.

Water-Oriented Facilities

Swimming pools. The proper size for a swimming pool (Table 10) will be determined by the number of people using the pool, the approximate distribution of divers, swimmers, and waders within that number, and, finally, the amount of money available for construction.

Table 10

Swimming Pools

| % of Pop. At Any One Time | Sq. Ft. of Water Per Swimmer | Total Area | Deck Area | Parking Required | Service Radius | |

| Public Outdoor Recreation Plan (Cal.) Neighborhood pool Community pool |

2% 6% |

30 30 |

1,000 sq. ft. of water surface 4,500 sq. ft. of water surface |

20 cars 75 cars |

Walking distance 2 miles |

|

| Athletic Institute* | 10 ft. on side of pool; 20 ft. on end of pool | |||||

| National Recreation Association | 3% | 15 (in the water or not) | 1 acre for a neighborhood pool — several acres for large pool | 3 to 7 acres depending on location | Variable | |

| Streator, Illinois | 3–5% | 27 | Ratio of 2 sq. ft. of deck area for each sq. ft. of water area |

*Further recommendations by the Athletic Institute includes: minimum length, 75 feet; minimum width, 35 feet; minimum depth, 3 feet; and maximum depth, 10 to 12 feet.

Experience has shown that several moderate size pools, properly constructed, with adequate water treatment and strategically located, will serve the community better than a single, very large swimming pool. The trend is definitely toward smaller pools which meet official regulations and specifications.

Public pools are generally designed to accommodate the maximum attendance at one time on an average day. As in many other municipal facilities, it is not economical to design for the days of maximum attendance, since the cost of maintaining a pool adequate for peak loads would be prohibitive. Overcrowding on peak days is preferable to excessive space and high operating costs throughout the swimming season.

A swimming pool should be located near the people it is to serve. The general location for pools should be determined by the walking distances between the pool and the areas to be served, the adequacy of public transportation, the absence of soot, dirt, and smoke from heavy industry, and the availability of adequate areas for off-street parking.

The swimming pool is one facility for which the most expert and all-inclusive planning and design advice is needed. It is imperative that all work be continuously inspected as construction progresses to make certain that the pool is constructed according to specifications.

Swimming Beaches. Swimming, playing in or near water, sunbathing, surf-boarding, and scuba diving are all becoming increasingly popular. It is impossible to set up standards for swimming beaches since there are so many variables involved. However, the California Public Outdoor Recreation Plan12 suggested some standards. (See Appendix E.)

The standards are based on optimum rather than a peak-day attendance. For shoreline swimming, 10 effective feet of shoreline will provide space for 20 persons at any one time. One effective foot of shoreline is defined as one lineal foot of shore with the following: 100 foot wide band of water suitable for swimming; 200 foot wide strip of beach for sunbathing and play; 100 foot wide buffer zone for utilities and picnicking; and 265 foot wide strip for parking where attendance is dependent on automobiles.

For every 1,000 people in attendance, 25 effective feet of shoreline are needed. In warm climates one effective foot will furnish many more days of swimming than it will in a cold climate, but about the same percentage of the population will attend on the normal, heavy weekend (optimum) day in both climates.

In 1953 the National Recreation Association polled a number of beach authorities in the Middle West. The survey indicated that an ideal beach would have a minimum length of 600 feet and a minimum depth of usable land of 150 feet. They also thought that a beach more than 3,600 feet long was undesirable because of difficulties in administration.

Westchester County standards call for 150 square feet of beach for each person using a beach. The County recommends that a minimum of 10 acres be reserved for a city beach and 50 acres for a county beach.13

Desirable features for the swimming beach are concession facilities at major centers of activity, walkways, bathhouses, space for out-of-water recreational activities, and a landscaped park to provide a pleasant setting and a buffer for nearby residences. The NRA has proposed minimum space requirements for beaches and related areas at 400 square feet per person.

Boating. There has been an explosion from 15,000 pleasure boats in 1904 to a phenomenal eight million pleasure boats of all kinds in 1960. It is estimated now that there will be more than 12 million pleasure boats by 1985.

The physical attributes of a site for boating facilities are of the utmost importance, for in the final analysis it is the placement of the facility and its form of development that determine its success. Physical considerations are the first and last steps in the planning of recreational boating facilities.

Of the various facilities for recreational boating discussed in this report, all have the common purpose of providing the boatman a point of transition from land to water. At the extreme is the marina, a comparatively elaborate facility that caters to the needs of the boating enthusiast as well as to interested non-boaters. In contrast, however, a simple launching ramp is often of great value by providing nothing more than access to the water.

The sizes of boating harbors or marinas vary greatly. The size and location are determined by the estimated number and size of the present and future permanent and transient boats to be accommodated and by the amount and characteristics of water and land areas available. The ideal location is a partially landlocked cove or lagoon protected from swiftly flowing water. Accessibility by car, a location in or near a park, and access to cruising water are all important factors in the placement of a boating facility.

A complete marina provides most of the following facilities: boat slips; boat handling equipment; repair and maintenance shops; marine and hardware supply store; boat and gear storage; launching facilities; fuel station; lockers and sanitary facilities; restaurant; clubhouse; motel or boatel; commercial stores; recreational facilities, park, and picnic grounds; spectator area; pedestrian area; and automobile parking.

As noted in PAS Report No. 147, Recreational Boating Facilities, June 1961, many marina operators believe that there should be a minimum of 250 slips and a land area of 25 acres for financial success. With fewer slips, berthing fee receipts will be so minimal that the cost of construction and maintenance cannot be justified. Twenty-five acres is considered to be the minimum area that will accommodate the operations of a marina of 250 slips and ensure adequate vehicle parking.

A small boat dock is designed to accommodate craft 12 to 20 feet in length at fixed or floating docks. To fix berths for 100 craft up to 20 feet in length would take a minimum of five acres of water. In addition to berthing equipment, more complete facilities may include some of the elements of a marina.

Mooring sites accommodate boats in protective coves or lagoons. Piles or buoys are used for mooring and a dinghy is needed for taxi to and from each craft. The amount of space required depends largely on the size and number of boats moored. It is recommended, though, that there be one automobile parking space for each mooring spot.

An access unit or launching ramp site is a facility for the launching and beaching of water craft carried on a trailer. Areas for the parking of automobiles and trailers are a necessity at this type of facility. Sometimes one or more docks are constructed at a launching site to expedite the operation.

The California Public Outdoor Recreation Plan states that

. . . the standard yardstick for measuring boating opportunity is the access unit. One access unit is defined as a facility capable of launching one boat at a time and serving 125 trailer boats or storage facilities, berthing, mooring and the like, for 100 non-trailer boats. In either case, adequate access, parking, and service facilities should be provided and about 160 surface acres of water suitable for boating should be immediately available. It is anticipated that 75 boats will operate from one access unit on the season's peak day and 50 boats on an optimum day.

Each self-launch area must be given individual consideration. Initial layout depends on the character of lake frontage, fluctuation of the water level, overall size of the area, topography, protection from prevailing winds, and the type of soil, not only in the parking or turnaround area, but also at the lake bottom directly adjacent to the proposed launching site. The turning radius of the average car and 14 foot trailer is about 45 feet. This radius increases to about 80 feet with larger rigs. The average car and trailer require a parking area of eight by 40 feet; however, 10 by 45 feet is desirable for unloading gear and opening doors. The turnaround area should be located as close to the ramp as possible so that all back-up operations will be confined to the launch area itself. The entire parking and loading area should be finished off with a one per cent slope for drainage.

A launching area should extend gradually into the water. The ideal slope is about 10 per cent (one foot in 10 feet) and should not exceed 15 per cent, unless the immediate water is deep at all times during the season.14 If this situation exists, the ramp should be planned so that only the trailer will be on the slope. The car should remain on the level or on a broken slope area having less than a 10 per cent pitch to the level ground of the turnabout area.

The ramp or launching area itself may be developed in many ways. A minimum width of 14 feet should be allowed for the ramp with the length depending on the depth and fluctuation of the water. A ramp 20 to 25 feet wide is ideal and affords space for maneuvering the trailer down the ramp without disconnecting the trailer from the car.

Winter facilities

Winter recreation as used here refers to sports and activities that are dependent upon snow or below freezing temperatures, particularly snowplay, skiing, ice skating, and tobogganing, and in some measure sightseeing.

Adequate parking space and its snow clearance are the two biggest problems for those who provide wintertime activities. The requirements for snow play areas, as stated in the California Public Outdoor Recreation Plan, are snow-covered surfaces, flat to a grade of 20 per cent, with a large, nearly level area for parking.

Skiing. Skiing has attained widespread popularity in the last few years. Wherever possible, opportunity for skiing should be provided in public recreation areas. Skiing requires the most extensive and specialized facilities of any outdoor winter sport.

Ski slopes should be long and various enough to interest the skier. The report Recreation-Vacation-Tourism in Northern Berkshire, Massachusetts, recommends that the vertical drop of a ski slope should be at least 600 feet or more. Major ski runs in northern New England have vertical drops up to 2,000 feet or more for the experts and for racing.

A ski area should be located where it will be protected from prevailing winter winds, both for the customers' comfort and to prevent excessive wind action on the snow.

Slopes should have gradients mostly ranging from 20 to 35 per cent. Novice skiers require anywhere from 10 to 25 per cent slope, while intermediate skiers generally prefer from 20 to 35 per cent. Gradients in excess of 35 per cent are found on trails or slopes for the most advanced and expert skiers.

Slopes must be smooth enough to allow skiing with a minimum of snow cover. In the California Public Outdoor Recreation Plan, requirements for skiing include snow-covered slopes facing north that have a minimum grade of 20 per cent, and ranging as high as 40 to 50 per cent slope. The report also recommends that there be one acre of slope for every 30 skiers, with one acre of parking for every 10 acres of skiing slope. It is also commonly thought that the best snow conditions are usually found at high altitudes, preferably above 2,000 feet.

For artificial snow-making, below freezing temperature is necessary. It is also generally accepted that open slopes facing south should be avoided. Thawing followed by freezing will make for an icy crust. To avoid both wind and sun, the best exposure is toward the northeast.

A ski jump for expert competition must be built with accurately determined proportions between height, slope, inrun, dimensions and location of the take-off, and the slope and position of the landing hill. A slope of 25 degrees is usually satisfactory for the inrun with a gradual leveling off near the take-off point. The landing slope, however, requires a 30 degree slope or greater, free from obstruction, and at least 30 feet wide. The landing slope becomes less steep near the foot of the hill and gradually levels out in the outrun.

Ice Skating. Slow moving streams and ponds make the most satisfactory skating areas; but where they are lacking, rinks may be formed by either flooding or spraying. Flooding has proved successful on large areas such as baseball and football fields and on general play areas with a concave surface, when soil conditions are such as to prevent the water from seeping away. Building an ice surface on the ground by spraying is often more satisfactory on small, unpaved areas. Several cities have experimented with a white plastic or vinyl film as lining material for an ice rink. This retains water and retards melting of ice but is hard to apply and easily cut by skates.

In Recreation Areas, George D. Butler recommends that the ideal size for a municipal ice skating rink is 85 by 185 feet. The ice hockey rules of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, which govern most amateur play in this country, specify the following: the rink or playing surface is a clear field of ice at least 60 feet by 160 feet and not greater than 110 feet by 250 feet. A rink 85 feet by 200 feet is recommended; this rink should have rounded corners with a 15 foot radius, and should be surrounded by a wooden barrier three to four feet high, preferably cream in color.15 The goal cage should be placed at each end of the rink at least 10 feet from the end boards and equally distant from the side boards.

A rink 85 feet by 185 feet has a capacity for 800 persons, although all skaters cannot be on the rink at one time.16 Another basis for determining a rink's capacity is to allow 30 square feet per skater; 20 square feet is considered the minimum and makes for a congested rink.

Features that are desirable for a skating rink are: night lighting; warming shed or a shelter house; music (when possible); runways (so skaters can reach the ice without walking over concrete or earth surfaces); pleasant landscaped setting.

Toboggan Slides. Tobogganing can be one of the most thrilling of all winter sports. Tobogganing, however, requires a considerable amount of space and fairly steep slopes. Natural slopes are sometimes used, but because of the difficulty of steering and controlling the sled, specially constructed slides are more desirable. The slide should be on a hill facing north or northeast. If the slope is wooded, trees can protect the slide from the sun's rays, and the direction is therefore less important.

On a wooded slide it is important that the slide be wide enough, but not so wide that the toboggan has a chance of jumping the track. If a slide is fast or is built on a steep slope at the start, a hinged tilting frame to facilitate safe operation is recommended.

Trees provide an attractive setting for the slide, and give the riders a sense of traveling at a greater speed. It is advisable that the slide be designed so that its entire length can be seen from the starting platform.

A toboggan slide need not be completely permanent. The slide can be constructed so it can be disassembled except for the platform and top part of the slide. This allows use of the area for other purposes during the summer months. The toboggan slide is more suitable for the playfield than the playground.

The earthen slide is perhaps the easiest to build. All that is needed is a trough dug one foot below the ground level and approximately 30 inches wide. The dirt taken from the trough is then packed along the sides of the slide and the area completely sodded.

The outrun of the wooden or earthen slide must be level to prevent the toboggan from upsetting. Lighting is an essential element for night use, and it is recommended that lights be spaced 100 feet apart, 25 feet above the ground, and as far as 30 feet away from the slide.

Golf Courses

The best golf courses will be on land specially selected for the purpose. Uneven, but not rugged, topography, some woodland, a good soil such as sandy loam, and good drainage are desirable characteristics of a site. Courses are made interesting through variations in the length of the holes and the width of the fairways, introduction of hazards, and the utilization of topography and natural tree growth.

As noted in Table 11, a nine-hole golf course requires 50 acres or more; an 18-hole course should have a minimum of 100 acres but usually is 120 acres or more. Authorities agree 17 that the "ideal" nine-hole course should measure over 3,000 yards, preferably around 3,200 yards, with a par of 35 to 37.

Table 11

Golf

| Min. Acreage Required | Population Served | Max. Acreage Required | Service Radius | |

| Local Planning Administration | 9 hole, 50 acres; 18 hole, 100 acres | 1 hole per 3,000 persons served; 27,000 pop. for 9 holes | 9 hole, 90 acres; 18 hole, 180 acres | Easy driving distance and access to public transit |

| National Golf Foundation | 9 hole, 50 acres; 18 hole, 110 acres | 18 holes for 20,000 population | 9 hole, 60 acres; 18 hole, 120 acres (Gently Rolling) 9 hole, 70 acres; 18 hole, 140 acres (Rough Terrain) |

|

| National Recreation Association | 9 hole, 50 acres; 18 hole, 100 acres | 1 hole per 3,000 persons served; 50,000 to 60,000 pop. for 18 holes | 9 hole, 75 acres; 18 hole, 160 acres | |

| Guide for Planning Recreation Parks in California | 18 hole, 160 acres | 18 holes for 20,000 pop. plus 1 18-hole course for every 30,000 thereafter |

In Planning and Building the Golf Course, the National Golf Foundation gives the following tips on course layout and planning:

The distance between the green of one hole and the tee of the next should never be more than 75 yards, and a distance of 20 to 30 yards is recommended. Trees should not be closer than 20 yards to a green because of the danger of being hit by an approaching golf ball.

The first tee in the ninth green of the course should be located immediately adjacent to the clubhouse. If it is practical without sacrificing other factors, bring the green of the sixth hole also near to the clubhouse. This is a feature appreciated by the golfer with only an hour to devote to his game, as six holes can be comfortably played in that time.

As far as is practical, no holes should be laid out in an east to west direction. The reason for this is that a maximum volume of play on any golf course is in the afternoon, and a player finds it disagreeable to follow the ball's flight into the setting sun.

The first hole of the course should be a relatively easy par-4 hole of approximately 380 to 400 yards in length. It should be comparatively free of hazards or heavy rough where a ball might be lost and should have no features that will delay the player. This gets the golfers started off on their game as expediently as possible.

Generally speaking, the holes should grow increasingly difficult to play as the round proceeds. It takes a golfer about three holes to get warmed up, and asking him to execute difficult shots while he is still "cold" is not a demand that he will appreciate.

Whenever practical, greens should be plainly visible, and location of sand traps and other hazards obviously apparent from the approach area.

Generally speaking, fairways sloping directly up or down a hill are bad for several reasons: (a) steep sloping fairways make the playing of the shot by the majority of players a matter of luck rather than skill; (b) the up and down climb is fatiguing to the golfer; (c) turf is difficult to maintain on such an area.

The par-3 holes should be arranged so that the first of the two is not earlier in the round than the third hole and the other one is not later than the eighth hole. Par-3 holes should not be consecutive.

Robert Trent Jones, golf architect, set forth points18 that are generally agreed on by members of the American Society of Golf Course Architects:

On level or flat land a 9-hole course of 3,100–3,400 yards can be laid out in approximately 50 acres but it will be cramped. An 18-hole course of 6,200–6,500 yards or more would require at least 110 acres. This is a minimum, making the routing of the course extremely tight. Gently rolling land requires approximately 60 acres for 9 holes and 120 acres for 18 holes. Hilly or rugged land will require considerably more because of the waste land where the contours are severe. At least 70 acres will be needed for 9 holes and 140–180 acres for 18 holes.

The backbone holes of the modern golf course are the 2-shotters, of 400 yards or over. The length of the 2-shot hole offers plenty of opportunity to develop good strategy. The short hole should be kept under 200 yards so that every golfer has an opportunity to reach the green with a good shot and thereby obtain his par or birdie.

The minimum length for a standard 18-hole golf course is 6,200 yards. A good average is 6,500 yards, and championship length is 6,700–6,900 yards. The short hole should range from 130–200 yards (par-3) and there are generally four of these holes, but there may be five. Par-4 holes should range from 350 to 450 yards and there are generally 10 of these. Par-5 holes should range from 450 to 550 yards, and there are generally four of these.

Fairway width generally is about 60 yards, but will vary depending on the type of players expected to play the course, and the strategy of the play of the hole. A yardstick of fairway width is as follows: 75–120 yards from the tee the fairway will be 40 yards wide; 120–180 yards from the tee the width will be 50 yards; 180–220 yards from the tee the width will be 60–70 yards.

The green sizes will vary from 5,000 to 8,000 square feet, depending on the length of the hole and the length of the shot called for.

Additional standards as developed in the California Public Outdoor Recreation Plan, Part II, include:

| Type | 18-hole course |

| Development | Minimum size for a layout and effective operation is 120 acres including necessary auxiliary facilities such as clubhouse, restaurant, and parking. |

| Parking | Space for 200 automobiles. |

| Type | 9-hole course |

| Development | Minimum size for layout and efficient operation is 60 acres including necessary auxiliary buildings. |

| Parking | Space for 100 automobiles. |

Note: Additional desirable facilities at the golf course are putting greens and driving ranges, These facilities require additional parking space.

The par-3 course, which is becoming increasingly popular, is a short golf course, with the fairways and greens smaller than those of a regulation course but paralleling the larger course in every other way (Table 12).

While most short courses are properly called par-3 courses, designed so that no hole exceeds the maximum yardage of 250 yards set by the United States Golf Association for par-3 holes, a number of short courses feature a few par-4 holes and even an occasional par-5 hole. The par-3 plan, however, is most significant as an innovation, and it is the par-3 golf course that this report will discuss.

The par-3 course is definitely not a substitute for the longer regulation golf course, although in areas where there are no regulation courses, or where courses are crowded, it will absorb the overflow of play. While the short course owes much of its rapid growth in popularity to the great demand for golf facilities and the inability of an accelerating golf course development program to catch up with this demand, the par-3 course is carving out a place of its own by virtue of its special appeal.

The average par-3 course of nine holes will require from 45 minutes to one hour to play a full round.19 This fact attracts many working golfers, particularly during the week when they cannot spare the three to four hours required to play a regulation nine-hole course.

A par-3 nine-hole course can be built on as little as five acres. However, some of the larger installations will have 18 holes distributed over as much as 60 acres. While five acres is adequate for a very short nine-hole course, it is wise to buy additional land to provide for expansion.20 In estimating the area required, space for adequate parking, clubhouse facilities if desired, and shelter for maintenance equipment and tools should be provided.

Figure 3

Nine-hole, par-3 course designed for maximum land use at minimum cost. Grassy bunkers and hollows can be substituted for sand traps indicated on plan to further cut cost of construction and maintenance as well as to speed up play for greater traffic capacity. Designed for 15 acre area.

Source: Golf Operators Handbook. Edited by Ben Chlevin. National Golf Foundation, Inc., 1956, p. 86.

Table 12 shows some possible yardage combinations for nine-hole par-3 courses with total yardages of 450, 900, and 1,350 yards. (The National Golf Foundation is the clearing house for information on golf activities and facilities. Several of the National Golf Foundation publications, listed in the bibliography, have been extremely useful in putting this section of the report together.)

Table 12

Nine-Hole, Par-3 Yardage Plans

| Hole No. | Yards | Yards | Yards |

| 1 | 140 | 125 | 70 |

| 2 | 165 | 105 | 45 |

| 3 | 155 | 75 | 55 |

| 4 | 90 | 100 | 30 |

| 5 | 200 | 140 | 80 |

| 6 | 160 | 65 | 40 |

| 7 | 120 | 90 | 60 |

| 8 | 175 | 115 | 25 |

| 9 | 145 | 85 | 45 |

| Total | 1,350 | 900 | 450 |

| Average | 150 | 100 | 50 |

Source: Golf Operators Handbook. Edited by Ben Chlevin. National Golf Foundation, Inc., 1956, p. 78.

Camp Sites

Standards for four types of camping activities have been suggested in California's Recreation Plan, Part II:

| Type | en-route |

| Development | 10 units per acre |

| Parking | one car space and space for trailer per unit |

| Type | organizational |

| Development | five acres developed with permanent facilities and structures for eating and sleeping to accommodate 100 persons |

| Parking | minimum 50 spaces |

| Type | group |

| Development | five acres with sanitary and basic cooking facilities and open space for bedding or tents sufficient to accommodate not more than 50 persons for short periods of time |

| Parking | minimum of 25 cars |

| Type | family with tent or trailer |

| Development | four units per acre (unit consists of table, cooking facilities, space for tent or bedding and screening) |

| Parking | one car space for every unit |

Some site development standards for camping were suggested at the American Society of Planning Officials Annual Conference in Minneapolis, Minnesota.21 Camping and picnicking units should be at least 100 feet apart to preserve the forest cover and to provide privacy. A camping unit should consist of a platform or area for pitching a tent; tables and benches; and nearby water supply, cooking, and sanitary facilities. Areas should be easily accessible to roads or trails. The terrain in site areas preferably should have a 10 per cent slope, but should not exceed 20 per cent. Recommended also is the adoption of four persons per unit as the average capacity for all types of facilities. Minimum, maximum, and optimum density standards can be applied to camp and picnic units. At a capacity of four persons per unit, these units should be spaced no closer than 100 feet apart of five per acre in staggered arrangements in the forest areas, and in more intensive areas no closer than 50 feet apart, or 10 units per acre.

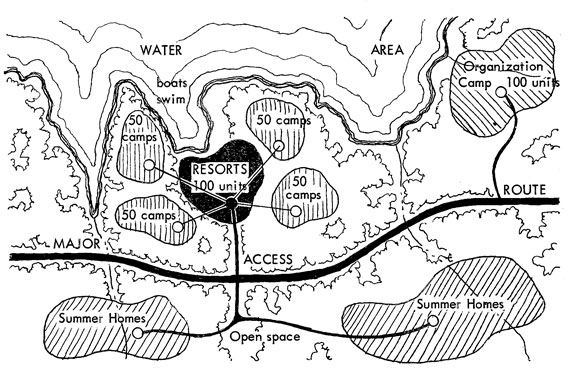

Scattered camp development is undesirable from the standpoint of aesthetics, economics in construction, and maintenance and administration. Scattered development hampers good forest and land management practices. Consequently, cluster standards have been devised to cover each camping recreation facility, based on construction economics and administration, and on the necessity for protecting the recreation resources by providing for large open areas between clusters. The camp and picnic clusters should be planned for a minimum of 25 and a maximum of 50 units per cluster (see Figure 4 for cluster recreational facility for year 2050.) The area of the site should be at least five and no more than 10 acres for each cluster. Design considerations, of course, must be related to topography and cover and standards may have to be modified in certain instances.

Figure 4

Maximum and Minimum Recreation Unit Standards (Clusters) by Type of Recreation Facility at Ultimate Development, Year 2050.

| Units per Cluster | Site Area (acres) per Cluster | |||

| Recreation Use | Minimum | Maximum | Minimum | Maximum |

| Camp and Picnic | 25 | 50 | 5 | 10 |

| Organization Camp | 25 | 100 | 20 | 125 |

| Resort, hotel, motel | 6 | 100 | 2.4 | 40 |

| Summer Home | 1 | * | 1 | * |

*Summer home clusters should be large enough to justify the provision of services, and number and size of areas permitted should be based on the ability of the land to support them and maintain the "outdoor" character.

Figure 4

Source: Recreation Planning in Natural Resource Areas. By Samuel E. Wood. Presented at the Conference of the American Society of Planning Officials, Minneapolis, May 10–14, 1959.

Picnic Sites

Picnicking facilities should be developed so that there is a proper balance among the three major types of facilities: those within communities, those outside the communities (beyond the metropolitan fringe), and those along highways. The family picnic unit should consist of a table and benches with nearby water supply, cooking, and sanitary facilities. Auto parking space and proper access are additional requirements.

Within the city, people will travel an average distance of five miles from home to a picnic area. Picnic areas located within the community should have no more than 16 picnic units per acre, with each unit accommodating not more than eight persons.

For large groups, the same type of facilities are needed, but less space is allotted to each picnicker. For an organized group picnic area within the city, 200 persons per acre is desirable. It is also recommended that an additional one-third acre for each group area be provided to accommodate 50 cars.

In picnic areas located on the fringe of the city somewhat different standards have been suggested. Here, eight units per acre is the recommended standard with one parking space provided for each unit.

For wayside rests, along major highways, units should be planned at a maximum density of 16 units to the acre, with no fewer than four units at a single location.22

Riding and Hiking Areas

General guidelines for riding and hiking trails have been suggested in the California report:23

| Type | hikes of one day or less |

| Development | well defined and maintained trail, up to ten feet in width, grades not to exceed five percent average with a maximum of 15 per cent. |

| Parking | minimum parking for 25 cars at any one access point. On short scenic, well known trails, the parking area might be expanded to 100 automobile parking spaces. |

| Type | overnight hikes |

| Development | well defined trail with average grades of five per cent and none to exceed 15 per cent. Three to five acre overnight trail camping areas should be provided at intervals of about five hours hiking time. |

| Parking | minimum for 10 automobiles at any access point. |

Additional hiking standards prepared by the Los Angeles Regional Planning Commission24 recommend that trail stops be located six to 15 miles apart, that pathways be a minimum of six feet in width, and that trails be a minimum length of six to 12 miles.

The California report also suggests standards for horseback riding: 25

| Type | rides of one day or less |

| Development | well graded wide tracks with interconnecting loop trails and numerous access points. Average grade should be five per cent and not exceed 15 percent. |

| Parking | a minimum space for 10 cars and stock trailers and a loading ramp or platform. |

Heavily used trails may need up to 80 spaces for cars and trailers. Adequate holding stalls, hitching racks, and water are of utmost importance.

| Type | extended trips |

| Development | the same as the one day or less rides with the stationing of overnight trail areas 12 to 15 miles apart, with the minimum size for these areas being three to five acres. Ample space should be allowed around development to allow for a buffer zone. If possible, water should be available every six miles. |

| Parking | the assembly areas or jump off points should be large enough to park vehicles and stock trailers. If the assembly area is also the base camp facility, it should be a minimum of 20 acres with the necessary basic facilities such as water and toilets. |

Footnotes

1. Clawson, Marion. Land and Water for Recreation, Policy Background Series. Rand McNally and Co., 1963, p. 19.

2. Ibid. P. 67.

3. Butler, George D. Standards for Municipal Recreation Areas. National Recreation Association. Revised edition, 1962, p. 6.

4. Ibid. P. 19.

5. Space in New Neighborhoods. National Recreation Association, 1939, p. 15.

6. A Guide for Planning Facilities for Athletics, Recreation, Physical and Health Education. Prepared by the Athletic Institute, 1947, p. 23.

7. Butler, p. 31.

8. Municipal Auditoriums and the City Plan. American Society of Planning Officials, Planning Advisory Service Information Report No.7, October 1949.

9. Butler, p. 30.

10. A Guide for Planning Facilities for Athletics, Recreation, Physical and Health Education. Athletic Institute, p. 101.

11. Ibid. P. 101.

12. California Public Outdoor Recreation Plan. Conducted by the California Public Outdoor Recreation Committee, 1960. Part I, pp. 46-48; Part II, pp. 48 and 84.

13. Butler, p. 32.

14. "Boats — In and Out of Water." In Boating Facilities, Outboard Boating Club of America, February 1964, p. 16.

15. Standards of Recreational Facilities. Bureau of Governmental Research, University of Washington, 1946.

16. Butler, George D. Recreation Areas. National Recreation Association, 1958, p. 166.

17. Planning and Building the Golf Course. National Golf Association, p. 20.

18. Ibid. P. 22.

19. Golf Operators Handbook. National Golf Foundation, p. 70.

20. Ibid. P. 69.

21. Wood, Samuel E. "Recreation Planning in Natural Resource Areas." Presented at the Conference of the American Society of Planning Officials, Minneapolis, 1959.

22. All statistics for picnicking were presented in the California Public Outdoor Recreation Plan.

23. California Public Outdoor Recreation Plan. Part II, p. 85.

24. ASPO Newsletter, September 1956, p. 67.

25. California Outdoor Recreation Plan, Part II, p. 85.

Appendix A

Rockland County Recreation Study Space Requirements for a Playground

| Required Space, Square Feet | ||||

| Area | Minimum | Maximum | ||

| Tot lot | 5,000 | 10,000 | ||

| Apparatus area | 4,000 | 8,000 | ||

| Wading pool | 5,000 | 10,000 | ||

| Free play area | 10,000 | 25,000 | ||

| Multi-use paved area | 20,000 | 30,000 | ||

| Field games | 120,000 | 180,000 | ||

| Court games | 40,000 | 80,000 | ||

| Quiet activities | 6,000 | 10,000 | ||

| Older adult areas | 3,000 | 5,000 | ||

| Shelter house | 4,000 | 8,000 | ||

| Landscaping | 10,000 | 20,000 | ||

| TOTAL | 227,000 (5.24 acres) |

386,000 (8.29 acres) |

||

Source: Recreation Study and Facility Plan, Rockland County (N.Y.) Planning Board, September 1960, p. 34.

Appendix B

Space Requirements for Typical Playfield

| Area | Acres | |

| Minimum | Maximum | |

| Fields for baseball, softball, football, and track | 8 | 12 |

| Tennis courts, horseshoes, basketball, volleyball, and shuffleboard | 1 | 2 |

| Tot lot and children's playground | 2 | 3 |

| Area for lawn games | 1 | 2 |

| Passive recreation area, including picnic benches and tables | 1 | 3 |

| Shelter with toilets and drinking water | 1/2 | 1 |

| Landscaped buffer areas | 1 | 2 |

| Swimming pool with a bath house | 1/2 | 1 |

| Off-street parking area | 1 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 16 | 28 |

Source: Recreation Study and Facility Plan. Rockland County (N.Y.) Planning Board, September 1960, p. 35.

Appendix C

Facilities Recommended for the Community Park

| Area in Acres | ||

| Facilities | Park & School | Park Separate |

| Playlot and mothers' area | .25 | .25 |

| Play area — elementary school children | .35 | .35 |

| Field for sports | 1.00 | 7.00 |

| Paved area for court games | 1.35 | 2.00 |

| Concrete slab for skating and dancing | .15 | .15 |

| Family and group picnic | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| Park area for free play | 2.00 | 4.00 |

| Area for special events | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Community center building | .75 | 1.00 |

| Regulation swimming pool | .50 | 1.00 |

| Natural area | 2.50 | 2.50 |

| Older people's center | ||

| Turfed area | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Paved area | .10 | .10 |

| Building space | .10 | .10 |

| Off-street parking | 1.00 | 1.5 |

| Landscaping (25 per cent of site is transitional areas and perimeter buffer) | 4.01 | 6.55 |

| Night lighting | .25 | |

| TOTAL | 20.06 | 32.75 |

Source: Guide for Planning Recreation Parks in California. California Committee on Planning for Recreation, Park Areas and Facilities, 1956, p. 58.

Appendix D

City-Wide Recreation Facilities Suggested Space Standards — Service Population of 100,000

| Facilities | Total Acreage, Including Parking | Parking Provideda | |

| Number of Automobiles | Acreage Required | ||

| Cultural Center (adjoining a major educational institution when practical) | |||

| (A) *Drama and music center (auditorium seating 1,000; intimate hall for chamber music) | 10 | 300 | 2.1 |

| (B) *Outdoor theater | 20 | 600 | 4.2 |

| (C) *Junior museum (science, crafts, art center) | 15 | 30 | .2 |

| (D) * Museum; art center with art gallery and studios for painting, sculpture, and crafts; floral display hall | 15 | 300 | 2.1 |

| (E) Landscaping: 25 per cent of total acreage of items starred | 15 | . . . | . . . |

| 75 | 1,250 | 8.6 | |

| Recreation Park | |||

| (F) Open meadow area | 30 | . . . | . . . |

| (G) Natural areas, trails, lake or water course | 45 | 150 | 1.0 |

| (H) Picnic and barbecue areas (family and group) | 30 | 300 | 2.1 |

| (I) Day and weekend camping | 30 | 300 | 2.1 |

| (J) Golf courses (one 18-hole course — 160 acres) Four courses provided on following basis: One 18-hole course for 20,000 population, plus one 18-hole course for each 30,000 thereafter |

640 | 1,600 | 11.2 |

| (K) *Children's wonderland (combined with children's zoo) | 5 | 10 | .7 |

| (L) *Play area for preschool children and apparatus section (four of each, widely separated) | 3 | . . . | . . . |

| (M) *Adaptable space for circus, carnivals, outdoor conventions | 20 | 600 | 4.2 |

| (N) Corporation yard | 10 | . . . | . . . |

| (E) Landscaping: 25 per cent of total acreage of items starred | 70 | . . . | . . . |

| 883 | 3,050 | 21.3 | |

a The parking standard proposed assumes joint use of parking areas. Allowance of 300 square feet per automobile.

| Facilities | Total Acreage, Including Parking | Parking Provided | |

| Number of Automobiles | Acreage Required | ||