Planning April 2016

Welcome to Black Rock City

What Burning Man’s temporary town teaches us about sustainable communities.

By Thomas Sullivan

"Wow!" I say through my aviation microphone to Major Tom, the pilot of an ultralight I somehow found myself strapped into."This is craaaazy!"

Seeing Black Rock City from 2,000 feet in the air on this September morning was scary, exhilarating, amazing, and really cold. Stretched out below us was the tan-colored Black Rock Desert, a 200-square-mile, silt-filled basin in northwest Nevada that's surrounded by brownish, rugged mountain ranges and hundreds of miles of desert.

In the spring, intermittent mountain streams fill the expansive playa with a thin film of water until it evaporates by summer, naturally forming a smooth tabletop finish, upon which a new city is built every year for the Burning Man Festival.

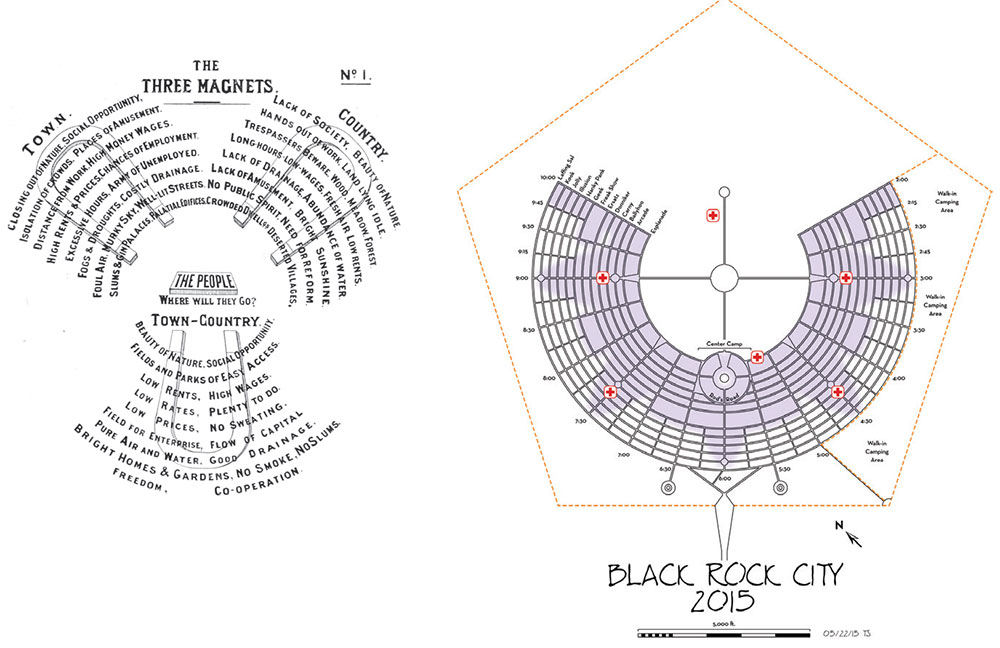

If urban planners shared my view on this beautiful Saturday they would surely recognize the resemblance to Ebenezer Howard's Garden City. It's as if a huge clock showing the hours from two to 10 was stamped onto the playa, where at the intersection of imaginary hands sits "The Man." He stands there patiently, waiting for dusk when he will be set on fire.

While this city resembles many of our own communities in the Mountain West — a mix of gated communities, suburbs, commercial-type districts, mixed use neighborhoods, and plazas — it is obvious that what is missing is the fast-paced car culture that dominates our "default-world" existence. Instead, from my vantage point, I spy Mutant Vehicles and Art Cars (for Burning Man definitions, see burningman.org/culture/glossary), flocks of pedestrians, and bicyclists by the thousands.

This is my fourth consecutive "Burn." While I am getting more comfortable at being uncomfortable (i.e., ultralight flying), I still remain in awe of the resourcefulness, innovation, and selflessness of nearly everyone I meet here. As an educator in sustainable planning and transportation, I find this an ideal place to study and learn how BRC is a living laboratory that, among a number of things, shows us ways to transition into more sustainable places.

Thousands watch as the Man is burned during Burning Man 2015 in the Black Rock Desert of Nevada on September 5. Approximately 70,000 people attended the sold-out festival. Photo by Reuters/Jim Urquhart.

"The Clock" from a few thousand feet. Black Rock City is best viewed from the open cockpit of an ultralight — if you're brave enough. Photo by Thomas Sullivan.

Utopian Resemblance: The city plan for Black Rock City (bottom) resembles another forward-thinking plan, that for Ebenezer Howard's Garden City (top). Howard's three magnets addressed the question, "Where will the people go?", the choices being "Town," "Country," or "Town-Country." Black Rock's map identifies community zones including art plazas, civic plazas, camping, and (of course) porta-potties. Source: Three Magnets, Wikimedia (CC-BY-2.5); Burningman.Org

Amsterdam on Mars

The busyness of bicycles reminds me of my first time at BRC in 2012. I was crouched down at the intersection of 9:00 and Dandelion taking a series of snapshots — one of hundreds — in hopes of capturing the "active" street life. Interrupting one of my photos, a burly, heavily bearded young man dressed in a toga placed himself into the frame, where he posed, flashed a smile, and jokingly mouthed something like — "Have a nice day, *%%#." So sets the mood of Burning Man, where, when a city's rhythm is slowed, interaction among its inhabitants is inevitable, and one's ease of being an active part of the community accelerates.

My bearded friend's intrusion only momentarily obscured my reason for being at this junction. When I first arrived on the playa, I was awestruck at the hordes of bicyclists and pedestrians that dominated the streets. I live a carless lifestyle in my hometown of Missoula, Montana, and I have always maintained a passionate interest in sustainable transportation, but this place far exceeded my expectations of what a city devoid of automobiles would be like.

Whether a Darkwad or Rave Chicken, a Sparkle Pony or Fluffer, everyone on the playa walks or rides a bicycle — with the exception of a few hundred Art Car and Mutant Vehicle drivers, Bureau of Land Management rangers, and Department of Public Works folks.

Stacked outside the hundreds of art exhibits and sculptures, rave parties and pubs, yoga sessions, and choir performances are literally hundreds of bicycles. No parking garages or traffic signs, traffic police, or pavement stripes are needed, as people rarely exceed the five mph speed limit and accidents are uncommon. And in fact, bicycles often become a reflection of the individual's personality while at the same time bringing people together.

Smart Growth, new urbanism, Slow Food, and Cittaslow (Slow Cities) are all organizations or movements that advocate, at least in some way, equality, community interaction, and a slowing down of culture. This actually happens in Black Rock City. And while the media often portrays it as a place where amazing art, hippies, and strange customs and costumes constitute a utopian-like metropolis, I look at the ways that sustainable forms of transport truly enhance connectedness, both physically and culturally, with the result of a greater opportunity for community living in ways that lessen the impact on our environment.

The 10 Principles of Burning Man

Burning Man cofounder Larry Harvey wrote the 10 Principles in 2004. They were crafted not to dictate how people should be and act, but as a reflection of the community's ethos and culture as it had organically developed since the event's inception.

- Radical Inclusion

- Decommodification

- Radical Self-Reliance

- Radical Self-Expression

- Gifting

- Communal Effort

- Civic Responsibility

- Leaving No Trace

- Participation

- Immediacy

Source: burningman.org

Ten simple principles and 'leave no trace'

Radical self-reliance and self-expression, immediacy, gifting — each comprising elements of personal fulfillment and responsibility — seem to effortlessly mingle with those community-oriented attributes of communal effort, decommodification, participation, civic responsibility, and radical inclusion. To me, Burning Man's "10 principles" (tinyurl.com/hqycvyt) are cemented through the overriding principle of leaving no trace. All are guidelines that evolved over decades of Burning Man festivals, eventually coalescing into loosely defined rules of urban living that are mostly enforced by its residents.

But a regulatory structure does exist in the city, especially since the festival occurs on federal land administered by the BLM. Years ago the agency, the Burning Man organization, and the Earth Guardians — a group of volunteers who promote and help to enforce environmental stewardship at the festival — reached out to and received sponsorship from the Leave No Trace organization, which trained a number of staff and volunteers at BRC. The result is an awareness and passing down of the LNT principles to all residents in a remarkable process where this city of 70,000-plus disappears almost as quickly as it appears.

I stopped by the Earth Guardians camp on a busy, research-driven Wednesday morning and visited with Lorax, one of the original camp organizers. She spoke of their newly developed program, where teams of Earth Guardians and BLM rangers go out and monitor camps. Those who do not adhere to LNT principles are cited for nonconformance. Armed with GPS units, these teams cover the entire city over the one-week period, mapping burn marks, gas spills, and MOOP (Matter Out of Place) while also educating city residents on the benefits of sustainable practices.

Leaving impressed by the diligent efforts of the Earth Guardians, I next visited Recycle Camp, where I met Mister Blue, the head of waste collection and recycling for the Burning Man organization since 2002. Since that time, Mister Blue estimates, they've doubled their can recycling efforts to roughly 175,000 cans, and his dream, much like the goals for a number of cities in the region, is to achieve "zero waste" at the event in the upcoming years. Ultimately, "it would be best if I was out of a job," he says, alluding to the notion that if all products and packaging brought to the event were compostable then no recycling would be needed at all.

A Mutant Vehicle made up like a polar bear drives through the dust during Burning Man 2015. Photo by Reuters/Jim Urquhart.

Exhausted and back home at Wonder Camp, I take a seat next to my friend I Don't Know under the awning of her small trailer. She is a retired train engineer, artist, and novice tobacco enthusiast. I watch as she lights up a roll-your-own cigarette. Taking a drag or two, she fumbles around for her Altoids tin — the ashtray of choice on the playa — frantically hoping to avoid a Sixteen Candles moment, finally finding it hidden on a small coffee table underneath a copy of BRC Weekly. She opens the lid of the small metal container and taps in the ash.

This most subtle of acts is rather ordinary behavior at BRC, and it helps me see the more individualized, bottom-up approach to LNT. Burners, most whom I found follow the 10 principles, are acculturated into a behavior based on the ideals of individual responsibility and environmental stewardship. So while there is a regulatory structure and organizations that practice a top-down approach to sustainable practices, the embedded notion that the individual is responsible for his or her actions is certainly evident.

Bikes are the main mode of transportation on the playa during Burning Man, and the "Man" himself — his legs are visible here — dominates the scene.

Festival-goers stay in tightly packed, dusty camps where personal hygiene takes a back seat to the principle of leaving no trace. Photos by Reuters/Jim Urquhart.

'It's not any worse than one day at NASCAR'

The next day, I returned to the Earth Guardians and asked Lorax if there were any themed camps that were more sustainable than most. "You mean like not taking showers?" she asks. Denizens of Pandora's Lounge — a nearby bike shop and bar — abstain from showers all week in order to reduce their graywater production. I reluctantly venture over toward their camp expecting to not need directions.

Camp organizer Allen Wrench explains how Pandora is a do-it-yourself bicycle maintenance shop, strictly adhering to the principle of self-reliance. From changing flats to oiling chains, their mechanics teach people life skills that Allen sees as one way for Burners to improve their and others' lives upon their return to the default world.

And while this camp advertises itself as a bike shop, some of the less conspicuous activities include recycling bicycle tubes (another camp uses them to make floggers — I didn't ask!) And chains (sent to the Chainspirations jewelry company), their use of solar panels to power lights and charge appliances — including the bar fridge, and of course the shower.

An activity that is gaining popularity among established camps is stowing camp materials in a storage unit in a nearby town to substantially reduce the amount of fuel required each year to set up. So while the festival is often criticized for being anything but carbon neutral, Allen says: "There are 70,000 people living in the middle of the desert for one week. You know, it's not any worse than one day at NASCAR."

Only a few streets over, I venture into Cartoon Commune/Green Reflections Camp, where I run into Lewis, the camp director, who shows me a number of smallish inventions that helped them to substantially reduce their footprint. In the kitchen, a milk crate full of papier-mâché fuel balls — a concoction of shredded paper, vegetable oil, and dryer lint — supply all the power needed for their Folgers coffee can "rocket" stove.

Strolling further behind the scenes, Lewis shows me his 10-foot-square cardboard house, complete with pop-bottle light and ceiling fan, natural air conditioning, a small solar array that powers their two dance parties and open-mic nights, a recycled T-shirt-walled community center/night club, and a wind-powered evaporator that eliminates nearly all their graywater.

My tour finished, I asked him what he thought about sustainable practices here on the playa. Was it possible for BRC to become carbon neutral (whatever that means)? "You can't preach to people," he says. "In fact, it is more about education, as you would be surprised how many people don't know about the little things you can do in living more sustainably."

The author's home at Wonder Camp, where sustainable practices such as water conservation, recycling, and leave no trace are passed down through the generations of Burners who live and work here. Photo by Thomas Sullivan.

No 'Sparkle Ponies,' just Wonder Horses

That Sunday morning in Wonder Camp — named after the plastic Wonder Horses that lead the camp's famous Stagecoach Art Car — I sit with my good friends Rosy and Driver on this final day of the festival. We reminisce about our first meeting in 2012 when they rescued me at the front gate in the midst of an epic brown-out. I'd ridden my bicycle eight days to BRC from Montana, and on my way in they nearly ran me off the road in their vintage Nevada Hotshot bus just outside of Cedarville, California. They felt sorry for me and I was invited inside. I've been with them ever since. Wonder Camp itself is a sort of strip mall that includes a Bike and Art Car Repair Shop, the Siren Salon, and a silkscreen shop — Splinter the Printers.

The 20-odd hardworking souls that live and work in and around the camp have a fundamental understanding that everyone adheres to the 10 principles. And for each new member, lessons in sustainable living are passed down. It is in this place where I learned how to live more sustainably.

I believe BRC is truly a model for how a change in our behavior is plausible. Calling Black Rock City the "greenest metropolis in the American West" is perhaps a bit of a stretch, especially when looking at it from a holistic perspective.

But what I see as most important is the impact that this place has on the individuals, who, like me, return to their communities in the default world and pass along elements of living sustainability to their friends and neighbors. In this sense, BRC, an incubator of sorts, is unlike any other place on Earth.

Thomas Sullivan is a visiting assistant professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Montana. His research and teaching emphasize the social and cultural aspects of active transportation, transportation infrastructure, and sustainable urban planning. Sullivan's playa name is Tutu (or 2-Squared), a name given to him by the Wonder Campers. (Yes, he has a tutu, also a gift.) Catch his session on sustainable practices in the Mountain West at the National Planning Conference: tinyurl.com/zokt6kx.

Burning Man Glossary (Abridged)

ART CARS: See Mutant Vehicle.

BURNER: One who pursues a way of life based on the values reflected in the 10 Principles of Burning Man.

DARKWAD: Anyone who walks or rides on the playa at night without adequate lighting on the front and back of his/her person or vehicle.

DEEP PLAYA: In Black Rock City, the area of open playa behind the Man, particularly the outer realms near the perimeter trash fence.

DEFAULT WORLD: The rest of the world that is not Black Rock City during the Burning Man event.

EARTH GUARDIANS: A subgroup of Burning Man participants who work with the BLM to care for the Black Rock Desert. Earth Guardians are trained in Leave No Trace techniques.

FLUFFER: A volunteer who supports other volunteer teams in the field, such as by replenishing their drinking water.

GREY WATER: "Used" water that has been contaminated by soap, toothpaste, playa dust, food residue, or similar pollutants. Though not as nasty as the "black water" of human waste, it needs to be carefully collected and removed from Black Rock City, never left on the playa.

MOOP: Matter Out Of Place. Litter, debris, rubbish.

MUTANT VEHICLE: A motorized conveyance that is radically, stunningly, (usually) permanently, and safely modified. Larry Harvey likens Mutant Vehicles to "sublimely beautiful works of art floating across the playa like a Miro painting." Licensed by the DMV, these vehicles are an important part of the Burning Man experience.

PLAYA: The Spanish word for beach, also used to describe dry lake beds in the American West such as the Black Rock Desert.

PLAYA NAME: Originally spawned by the need for unique names on the staff's two-way radios, playa names have become almost ubiquitous, and are sometimes used to provide an individual with an "alternate" personality or persona. Playa names are traditionally given to a person, rather than taken on.

RAVE CHICKEN: Someone who attends the Burning Man Festival or a rave and decorates himself in copious amounts of feathers. Inevitably some of the feathers fall off and become MOOP. Related to the Sparkle Pony.

SPARKLE PONY: Derogatory term for a participant who fails to embrace the principle of radical self-reliance, and is overly reliant on the resources of friends, campmates, and the community at large to enable their Burning Man experience. Often fashionably attired, since they pack nothing but costumes.

Source: burningman/culture/glossary/