Planning May 2016

Planning for the Car-Free Generation

Millennials are blazing new trails when it comes to transportation. Are you ready?

By Jonathan Sigall

By 2025, Helsinki, Finland, hopes to accomplish a revolution in the way its people get around. The goal: to make it unnecessary for city residents to have their own cars. City leaders propose a holistic transportation network offering a range of modes available on demand and that adjust in real time to current conditions and consumer demand.

Considering Americans' long-standing affinity for their cars, setting a similar goal for U.S. cities is not realistic, certainly not within the next decade. Still, travel behavior is shifting toward other modes, especially within the millennial demographic (aka Generation Y). Millennials, born between 1981 and 1997 — the exact span of years is not set in stone — are less car-oriented than older generations and more open to using multiple and alternative means of travel. As a result, they are making lifestyle and living choices that support their mobility preferences.

These changing dynamics are forcing major metropolitan areas to play catch-up, a daunting task given the price tag and lack of adequate funding. However, there is a flip side to this conundrum. The move toward reurbanization and away from the car offers planners an opportunity to build a less car-centric society.

Given the huge tax driving puts on the U.S., whether measured in productivity lost due to time stuck in traffic, increased emissions, or other factors, U.S. PIRG is correct when it stresses that "America should not just accommodate Millennials' desire to drive less, but actively encourage it."

Why plan around millennials?

So how much does all this matter? There are several reasons planners should get better acquainted with Generation Y.

MILLENNIALS ARE THE LARGEST POPULATION AND EMPLOYMENT BASE. A Pew Research Center report projected that the number of millennials would surpass that of baby boomers by 2015, with an expected population of 75.4 million last year. That number is only growing: it's expected to peak at 81.1 million in 2036. Millennials also account for the largest share of the workforce. As of the first quarter of 2015, there were 53.6 million millennials in the labor market, more than the 52.7 million Generation X workers and the 44.6 million baby boomers.

GENERATION Y IS LESS CAR-ORIENTED. Automobile use is down among all groups, according to a 2015 report from U.S. PIRG. In 2013, fewer Americans were licensed to drive than in 2008, and they drove 10 percent (or 330 billion) fewer miles than they would have had trends from the prior six decades held steady.

The drop is strongest among millennials. Nearly 30 percent said they were willing to give up their cars even if it meant paying more to get around, compared to only 11 percent of other groups, according to a 2015 survey by Deloitte. They are also less likely than other generations to buy a car or commute by car. Millennials are two to three times more likely to use transit, according to another study — this one by TransitCenter — and more likely to use more than one mode in a week.

MILLENNIALS ARE LEADING REURBANIZATION. Any number of studies point to an undeniable conclusion: Millennials prefer urban life more than older generations, even as a broader migration back to cities continues. In its report "America in 2015," the Urban Land Institute noted that millennials account for 42 percent of the nation's urban population. Baby boomers and Gen Xers represent only 25 and 23 percent, respectively.

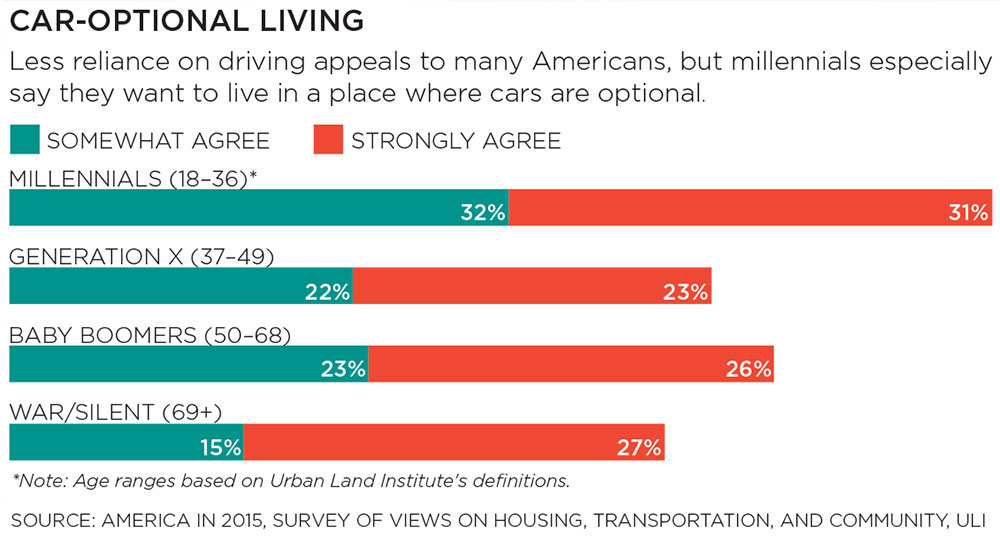

There are several underlying factors for Generation Y's preference for city living. Chief among them: Millennials don't want to live in a place where they're dependent on a car. They prize dense, walkable, and transit-rich communities with a diverse mix of uses and amenities.

THERE ARE LIFE STAGE DIFFERENCES. Millennials are marrying and starting families later in life. Others are forgoing marriage altogether — although marriage rates among all groups are significantly lower compared to the 1960s. Raising a family in the city and without a car poses challenges that suburban life with a car doesn't: Living quarters are more cramped, and toting young kids on transit is a daunting endeavor.

However, the choices of Generation Y may simply reflect the normal tendencies of young people, points out David King, an assistant professor of urban planning at Columbia University. Millennials may mimic their parents' life decisions once they marry and have children. They may find it desirable or even necessary to move to the suburbs, which offer more living space and more open space, and to own a car. The lean economic times are a factor as well, says King, who adds that the erosion of the middle class is contributing to the shifts.

Millennials say that they want to live in a place where owning a car is optional.

Implications for planners

Although millennials ultimately may be no different than their parents, there are numerous patterns that suggest otherwise. Adam Duininck, the chair of the Metropolitan Council in the Twin Cities, is a millennial with young children. He sometimes commutes to work by bike, dropping his children off at day care and school along the way. "I like to show up for work having gone for a bike ride," he explains, adding that it's more enjoyable and healthier than "being a frustrated commuter" stuck on other modes.

Duininck's experience is anecdotal, of course. But other data shows that he's not unique among his peers. Overall trips by transit, walking, and biking were up among 16 to 34 year olds in 2009 compared to 2001, cites U.S. PIRG (respectively, by 4, 15, and 27 percent per capita).

Floyd Lapp, FAICP, the former director of transportation for the NYC Department of City Planning and a professor of urban planning at Columbia University, believes the trends could be lasting, too. He notes that housing starts in urban areas are on the rise.

But even if trends eventually reverse, urban and transportation planners play a vital role in what the future looks like. We can reinforce and encourage lasting changes in behavior and demand through the land-use and transportation decisions we make.

New Jersey Transit's Midtown Direct service is illustrative. When it opened in 1996, it gave passengers on the Morris & Essex line a one-seat ride to midtown Manhattan, shaving 40 minutes (and a transfer) off the trip. Ridership surged 20 percent in the first year, to nine million. The connection spurred a housing boom, while the Regional Plan Association estimated that median home values rose by $90,000 for houses within walking distance of the Morris & Essex line. Granted, this example is from a densely populated area with a rich history of mass transit use. In the vast majority of places, the car is still king. But there are still steps we can take in communities of all sizes.

Constraints

However, to achieve a more sustainable future, planners must first overcome fiscal and organizational hurdles.

FISCAL CONSTRAINTS. In many urban centers, the money for transit improvements simply isn't there. Subway ridership is at record levels in New York City, but the system is literally a victim of its own success. Trains are often crowded beyond crush-load capacity, causing both unbearable conditions and self-propagating delays. Despite the MTA's need for renewed and expanded infrastructure, government support for its recent capital programs has been hard to come by.

Similarly, it took Congress until December 2015 to replace the MAP-21 transportation funding bill with a long-term measure, 18 months after it expired. Reluctance to adequately fund government services is at the root of the problem.

FRAGMENTED PLANNING. David King contrasts the New York metropolitan region to London. Where London Transport is responsible for all planning decisions and for transit operations, New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut lack such a cohesive framework. This fragmentation inhibits planning from a regional perspective.

ENTRENCHED COMMUNITY OPPOSITION. Various projects to improve the rail network in the Los Angeles metro area are stalled, including plans dating to the early 1990s that would extend the Metro Green Line in Norwalk by 2.8 miles and connect it with the Metrolink Norwalk-Santa Fe Springs commuter rail station. Partially because of community opposition, this link remains on the drawing board. Local opposition has likewise prompted the Los Angeles County MTA to place on hold and revaluate plans to expand capacity on a freight and commuter rail line in Northridge.

These obstacles don't mean there aren't answers or success stories. Solutions are both programmatic and structural in nature.

Programmatic solutions

NEW TRANSIT CAPACITY. Minneapolis-Saint Paul has expanded its transit system in recent years, notes Adam Duininck. It has added to its light-rail network and established rapid bus corridors, including the A bus line. The Metropolitan Council leveraged the renovation of an existing trunk road to get the A line built. Connecting the area's two Metro lightrail lines, the route is expected to be a big success, Duininck says.

BICYCLING. Biking is growing in popularity, led by millennials. Cities across the country are adapting to this trend by building hundreds of miles of bike lanes and offering bike-share programs. Portland, Oregon, is among the most bike-friendly cities in the U.S., with 350 miles of dedicated bike lanes, another 50 miles funded, and a reintroduction of bike share this year. The Twin Cities also rank among the country's best biking cities, boasting 129 miles of on-street bikeways and 97 miles off-street. Just last year, the region updated its long-term master bicycle plan.

ALTERNATIVES TO CAR OWNERSHIP. On demand car-share services (like Zipcar) and ride sourcing (Lyft and Uber) offer options. Ride sharing or carpooling is a tougher sell, says King. Commenting that pairing commuters together can be difficult and sharing rides with strangers can be uncomfortable and risky, he notes that decades of policies aimed at increasing carpooling haven't worked.

Nonetheless, Uber and Lyft are slowly testing the market for ride-sharing markets. That could be important: Carpooling can help take cars off the street by using otherwise wasted seats, notes Sarah Kaufman of New York University's Rudin Center for Transportation. The barriers King cites can potentially be mitigated, thanks to social media and smartphone technology, which connect people in real time and link them to someone they know. Other inducements include designated carpooling nodes and tax-benefit programs.

TECHNOLOGY. Smartphones and other technology allow for more flexible and ad hoc trip planning and payment, provide real-time updates on transit and traffic conditions, and facilitate alternatives to owning a car. Several transit properties either offer or are deploying mobile ticketing apps for riders. Agencies such as New York's MTA already provide real-time bus and subway information via smartphones. And increasingly, agencies are providing open-source data to app developers, which expands the range of mobile tools.

TELECOMMUTING. With advances in mobile, cloud-based, and wireless computing, workers are no longer tied to fixed locations and offices. Since telecommuting relieves pressure on traditional modes of commuting, urban areas should actively embrace it, as New York City is indirectly doing with its plans to blanket the city in Wi-Fi coverage.

Structural solutions

Unfortunately, fundamental changes in planning structures and financing are needed in many regions to achieve these gains. The New York MTA has many ambitious network improvement plans in the proposed 2015–2019 Capital Program, including advanced signal technology that will speed trips and enhance capacity along the Queens Boulevard subway corridor. But financing came together over a year after the program was slated to begin — so late in the game that MTA faced the prospect of running out of cash by June 30. The wrangling highlights the precarious and patchwork array of funding the agency and transit authorities rely on.

Floyd Lapp says there's a need for innovative financing, including public-private partnerships, in urban areas. In New York, Gov. Andrew Cuomo is proposing a PPP to build a rail link to LaGuardia Airport, while Indiana privatized the 156-mile Indiana Toll Road in 2006. It received a windfall of $3.8 billion by selling the rights to the road for 75 years. In exchange for collecting the toll revenue, the buyer assumed the burden of upgrading, operating, and maintaining the highway. Indiana is using the proceeds for such critical road investments as an extension of I-69 in the southwestern corner of the state.

Traffic pricing is critical, in King's view. If drivers don't bear the hidden societal costs of driving, they have little incentive to give up their cars. Establishing rational pricing for driving, as London has, can both reduce auto use and generate much-needed revenue for investments in other modes.

Move NY, a pricing scheme that would toll the now-free East River bridges in New York City while lowering the fees on the MTA crossings, would spin off billions of dollars in funding for transit and roadways. On March 24, it took a step toward reality when a coalition of 15 state assembly members introduced it as legislation, but the proposal faces a steep uphill climb. It wasn't part of the 2016 budget agreement and faces stiff opposition from motorists, businesses, and politicians. This despite economic forecasts that show it to be a win-win for almost everyone.

Regional coordination of efforts is another structural solution. In New York, a regional body that oversees transportation planning, funding, and pricing across all modes would facilitate improved and more holistic decision making, says King. London Transport and the Metropolitan Council in Minneapolis-St. Paul offer workable models.

The Twin Cities further benefit from a state land-use law — the only one of its kind in the U.S. — that requires local government bodies to coordinate land-use planning with regional plans for transportation and other major services. Sources there add that a strong and complementary relationship between the council and state DOT smoothed implementation of the A rapid bus line.

Going forward

Trying to plan around current generations can be like a dog trying to catch its tail. While some solutions can be implemented relatively quickly, many remedies take years, sometimes a decade or more to implement. In the meantime, millennials could eventually age out of their current preferences and lifestyles.

So is dramatic, or even incremental, decline in auto use achievable over the next 10 or 20 years? Maybe not. But one thing is for certain: Unless urban officials are responsive and adaptable enough to accommodate today's trends, we won't be able to allow for, or encourage, a less car-dependent future for future generations.

Jonathan Sigall is a transit financing and planning professional with 20 years of experience in the downstate New York metropolitan region. He currently works for MTA Long Island Rail Road. A version of this article originally appeared in the Winter 2016 edition of TPD News, a publication of the Transportation Planning Division of the American Planning Association.

Resources

"Are Millennials Really the 'Go-Nowhere' Generation?" JAPA, Volume 81, Issue 2, 2015: tinyurl.com/hcu5pkw.

Millennials in Motion, U.S. PIRG October 2014: tinyurl.com/ztwcrnw

Millennials in the workforce, Pew Research Center: tinyurl.com/mblretz

Smart Mobility, Deloitte University Press: tinyurl.com/jnr9jdf

2014 Global Automotive Consumer Study, Deloitte: tinyurl.com/gmxjj3u

Filling Up Seats in Cars: The Future of Driving: Every day we ignore a surplus of transportation capacity: the empty seats in the vast majority of cars on the road. But as driving attitudes, data, and technology change, it's becoming easier for people to share rides — taking cars off the road and easing congestion. Watch: tinyurl.com/h6abvku