Planning November 2016

A Course in Small Town Revitalization

A regional planning organization in New York’s Hudson Valley helps a small class of stakeholders achieve community-building success.

By Jonathan Lerner

Unlike other small urban areas in its region, the city of Middletown, New York, has been gaining population and jobs. About 28,000 people live there, a nearly 10 percent increase since 2000. Among its centers of employment and vitality are a community college and a state university branch; a college of osteopathy, which opened in 2014 in a disused hospital; and a satellite campus of an English-Chinese bilingual college that is moving into part of a former state psychiatric institution.

Middletown grew up in the 19th century as a rail hub, and has an attractive, intimately scaled and largely intact historic downtown. But rail and manufacturing disappeared in the mid-20th century, and retail moved to the outskirts — the typical story. While not one but two craft breweries — those heralds of urban renaissance — have opened recently downtown, many commercial spaces remain vacant. Residential neighborhoods are deteriorated, with a high poverty rate.

"There is this notion of moving back to cities and walkable communities," says Jonathan Drapkin, president and CEO of Hudson Valley Pattern for Progress, a nonprofit regional planning organization. Drapkin and others want to see that trend happen in small towns with good, urbanistic street networks and underutilized building stock.

Pattern for Progress is one group that's helping to do that, working with communities in the nine-county Hudson Valley area. This year, Pattern initiated a program called Community Builders, "a six-month intensive commitment of resources" to build leadership capacity in eight individuals who are championing "anchor projects that can encourage growth and revitalization in existing urban places," Drapkin explains. Two of these projects are in Middletown.

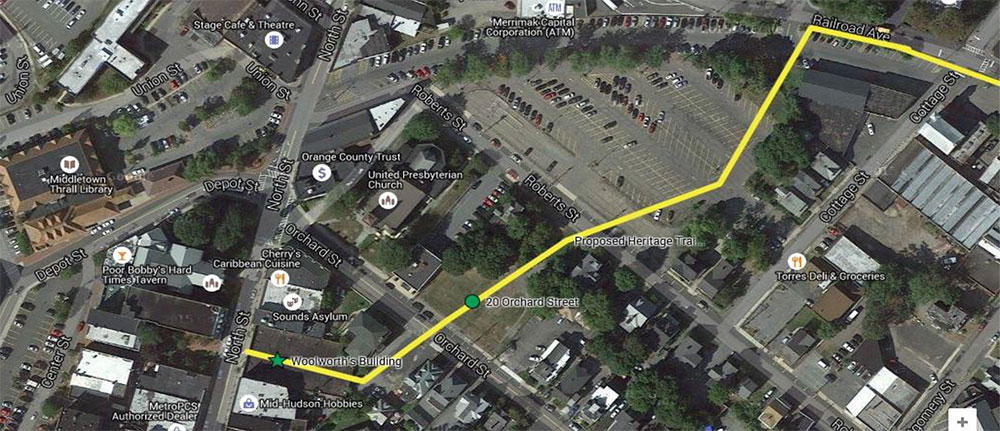

On the main commercial street, a 20,000-squarefoot former Woolworth store is to be transformed. An open-air pedestrian corridor will cut through its center, creating a connection to parking behind the building and functioning as the terminus of a spur off a rail trail under development that passes nearby. The remaining sections of the Woolworth building will be renovated into four turnkey retail spaces. "What's hampering us is the big empty stores," says Maria Bruni, Middletown's director of community development. "We have great retail starting, but we're running out of places for smaller shops." Besides enhancing connectivity, Rail Trail Commons, as the project is called, could be a model for adapting other problematically large buildings.

Post Office, City Hall, and Mitchell Inn, Middletown, New York, in 1935. Alamy image.

Downtown Middletown Capital Project Woolworth Building (Rail Trail Commons). The former Woolworth store has been vacant since 1994. Courtesy City of Middletown.

It will become Rail Trail Commons (retitled since rendering was created), which will offer four small retail spaces — a size in high demand — and connect to a nearby trail. The center of the building will be opened to create a pedestrian corridor, offering easy access to parking and the trail. Courtesy City of Middletown.

About a half-mile north, in a depressed neighborhood dominated by one- and two-family houses, many carved into smaller apartments, is the headquarters of the Regional Economic Community Action Program. Directly across the street sits an empty 41,000-square-foot former clothing factory. RECAP has developed more than 50 units of supportive housing in existing buildings in the neighborhood, and has additional plans for improving housing stock there.

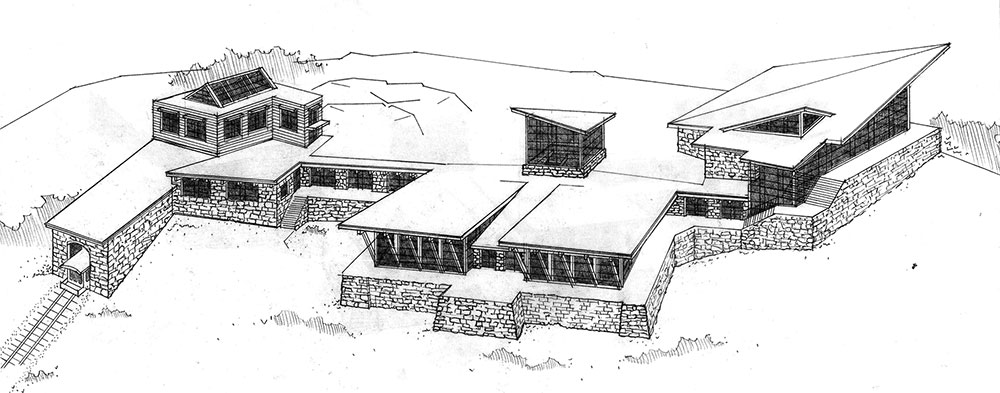

As a centerpiece of this renewal effort, they also propose to renovate the factory. In concept, the building could contain a Head Start program, a food pantry, a program for job training in solar energy services, and office and conference spaces for other nonprofits and start-up businesses. But RECAP COO Michele McKeon says, "I'm a social worker, I know how to fix human problems. Object problems that benefit humans are a leap for me." She didn't know "the technical process of starting from a shell and moving a building though the concept phase, the grant writing phase, the planning stage," or the process of preserving the historic building.

McKeon, Bruni, and the six other Community Builders participants met biweekly from January through June with Joe Czajka, Pattern for Progress's executive director and senior vice president for research, development, and community planning, and other technical staff . They did classwork to develop practical skills like using Gantt Charts, budgeting and leveraging resources, and understanding environmental reports and comprehensive plans. Even more important, the participants say, was the sharing of their projects' progress and challenges — and the mentoring they received both from staff and each other.

"Our projects are similar in some ways and dissimilar in other ways, but there's always something you can gain from somebody else's experience," says participant Lisa Silverstone. She is executive director of Safe Harbors, in Newburgh, a nonprofit promoting both affordable housing and the arts. Her project is the renovation of a former hotel and movie palace into a complex of performance, coworking, artists' studio, gallery, and retail spaces. Safe Harbors had already created 128 units of supportive housing in the building. In Community Builders, "there are connections to be made, in an environment that's nonjudgmental. Basically we're all placemakers. That's the thrust."

Downtown Middletown Capital Project Woolworth Building (Rail Trail Commons): Work will begin in late 2016 on the 12-mile, $12 million extension of the Heritage Trail from Goshen to East Main Street in Middletown, being developed by the Orange County Department of Parks, Recreation & Conservation. When it is completed at the end of 2018, a short spur will lead pedestrians to Rail Trail Commons. Courtesy City of Middletown.

The Lustberg & Nast Neighborhood Revitalization Plan, Middletown: Across the street from the office of the Regional Economic Community Action program is an empty 41,000-square-foot former clothing factory. RECAP wants to renovate the building to use for a Head Start program, a food pantry, job training, and office and conference spaces. It is near more than 50 units of supportive housing that RECAP developed. Photo by Jonathan Lerner.

50 years of Progress

Pattern for Progress was founded in 1965. Its membership comprises both individuals and organizations in government, business, academia, and the nonprofit sector. The small staff includes two people with master's degrees in regional planning, two others with degrees in economics, and Drapkin, who has degrees in both economics and law. Its general mission has always been to promote sustainable development and quality of life in the Hudson Valley.

It produces educational and networking programs for government leaders. It develops capacity and leadership through an annual fellows program for about 25 mid-career professionals, essentially "a course in regionalism," as Czajka describes it, and now through Community Builders. And it provides services, often on contract to municipalities, such as demographic and issues research, strategic planning, and grant writing.

Recently Pattern for Progress defined the priorities of educational improvement and urban revitalization. Both are aimed at keeping and attracting young people, while also aiming to preserve the valley's primarily rural character — a significant component of the economy, through tourism and agriculture — by encouraging growth in already built places.

But many of the villages, towns, and even cities in the region have no planning staffs at all. Most struggle with limited budgets and the legacies of disinvestment; unlike Middletown, the majority have lost population and employment opportunities, and continue to do so. Community Builders was conceived as a way to address those obstacles, by encouraging projects that will stimulate infill and economic growth. Pattern is one of a very few regional nonprofits to support small urban places that lack planning infrastructure; others include Handmade in America's Small Town Revitalization Program, in Western North Carolina; the Pennsylvania Downtown Center; and the Orton Foundation's Community Heart & Soul program, which works with towns across the country.

David Church, AICP, the planning commissioner for Orange County, New York, where Middletown and Newburgh are located, is a Pattern for Progress member. "Focusing on leadership and skills training, they fill a void," he says. His office, with a staff of 24, does take on projects in the municipalities. In Middletown, the county planning department is leading the redevelopment of a regional bus hub and, with the county parks department, creating the rail trail. But it also is responsible for grant writing for all units of the county government, and runs the county water authority, too.

"We have our own initiatives," he says. "But we have capacity issues. So Pattern's participation is valuable. There's some confusion sometimes when NGOs become essentially contractors, but we're comfortable with them stepping in."

Beacon, New York: The Mount Beacon Incline Railway Restoration Society wants to recreate a historic funicular that was destroyed by fire in 1983. The ambitious $40-million plan would include park infrastructure, a visitors center, and a restaurant at the top of the 1,600-foot peak, allowing visitors to connect with hundreds of miles of trails. It is complicated by cost and coordination with an adjacent town, a conservancy, and the state. Courtesy Mount Beacon Incline Railway Restoration Society.

Tangible steps

Community Builders, while designed to build technical and leadership skills, is strongly project-focused. For this first iteration of the program, one goal was that by the end of the six months, each participant's project should be ready to take a tangible step forward, for example, by having identified a funding source and being ready to apply. The program, which formally concluded in June, included a basic curriculum, but the content also was "built on the fly. We learned from the expertise and the desires of the participants," says Czajka. Based both "on their individual needs and commonalities, it was free-form learning, a swapping of ideas."

Most of the projects did meet that "tangible step forward" goal. Safe Harbors, for example, has applied for a Main Street Stabilization Grant from New York State Homes and Community Renewal to repair the roof of the old theater and to address architectural and engineering issues of further renovation.

Another project was moved forward by being scaled back. Beacon is a city of about 15,000 in Dutchess County, nestled between the Hudson River and a 1,600-foot peak. The Mount Beacon Incline Railway Restoration Society has been trying to recreate a historic funicular that was destroyed by fire in 1983, and enhance park infrastructure that is now rudimentary to nonexistent at the top.

From the summit, "you can access hundreds of miles of trails," that are now only reachable by vigorous hikers, says Jeff McHugh, the group's volunteer president. "It would be a one-of-a-kind destination in the valley, for experiential tourism," with universal accessibility. Beacon is only 90 minutes via commuter rail from Manhattan, which presents an enormous market of potential day-trippers.

The society's ambitious concept envisions not only a new funicular, but also station facilities at either end, and a mountaintop visitor center and restaurant. The project is simple in concept, but complicated because it requires coordination with the adjacent town of Fishkill, the state parks department, a conservation nonprofit which owns some of the property — plus it has a big price tag. "Jeff [McHugh] wasn't getting traction with a $40 million project that he's raised no money for," says Drapkin.

But as a result of the mentoring process in the group, McHugh says, he realized that breaking it into smaller chunks could help, by creating incremental successes and smaller steps that eventually could be folded into the larger plan.

As a result of the mentoring process in the group, Jeff McHugh, the society's volunteer president, says he realized that breaking it into smaller chunks could help, by creating incremental successes and smaller steps that eventually could be folded into the larger plan. He plans to start with the goal of producing a study for a road that would need to be rebuilt before anything else can happen. Courtesy Mount Beacon Incline Railway Restoration Society.

Peer mentoring

One of the benefits of the program is working through issues as a group. In Beacon, a crumbling emergency service road up the mountain is "one big storm away from being washed out," McHugh notes, and would need to be rebuilt anyway before other construction could go forward. "So what I'm proposing is to go back to the city and say, 'How about we find out exactly how much that would cost,'" McHugh said at a Community Builders class in April. Czajka suggested they might also talk to Dutchess County and Fishkill, and with Beacon, seek a shared-services grant specifically for the planning of that road. The exchange, which included others, helped McHugh realize that getting enough money for a study is a good start to the ambitious project. The brainstorm session was "the perfect example of how helpful it is to talk this stuff out with people who actually know," McHugh adds.

Not every one of the eight projects made such identifiable progress. "A lot of things are hard to move in six months, if you have a political issue, or grants to write," Drapkin says. But he says that although most participants can't realistically achieve their whole project in six months, they can conceptualize it. Drapkin asks them, "'Okay, what are the first two things you're going to get done? And by when?' [We get] them from day one of our program to say, 'Here's where I want to be at the end' — subject to change of course, then integrate some milestones."

To the surprise of Drapkin and Czajka — and the eight Community Builders themselves — at their final meeting they all insisted on staying together for a second six-month "semester" in 2017. Perhaps each "sophomore" will be paired with a member of the incoming group, or the two groups will alternate meeting separately and together. What else will differ remains to be seen. The first group's members are all professionals in local government or social service organizations, except McHugh, who is a business consultant. All already knew the Pattern staff.

"There was a strong willingness to say, 'Help us.' That may not be true in future years," Drapkin notes. "We're very interested in the not-for-profit world, and the community organizing world. That's a group with less of a skill set," he adds. "We want to make it known that you don't have to be a professional. But you have to come as a person with an idea, and explain it in a one-page application."

Appropriately, being nonprofit rather than governmental, Pattern has the ability to be nimble and reshape Community Builders to suit each new group of participants. As Joe Czajka observes, "Community development is fluid in nature."

Jonathan Lerner writes on architecture, environment, and planning and is a contributing editor to Landscape Architecture Magazine. He is also a communications consultant to professionals in those fields.