Planning April 2018

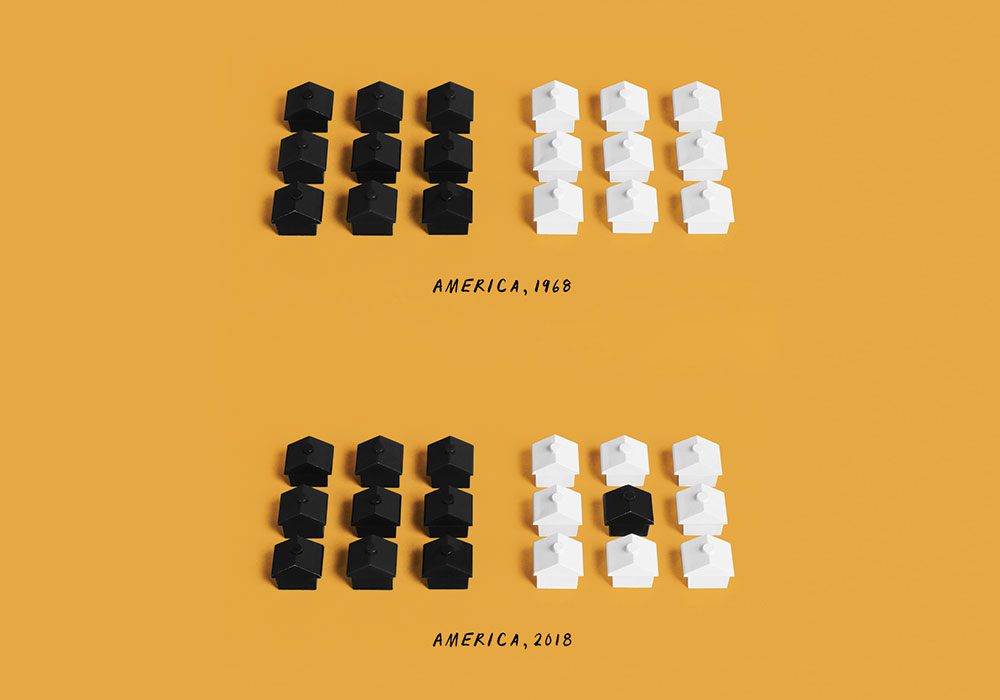

Fair Housing at 50

We’ve had a half-century to fulfill this promise. How have we done?

By Jake Blumgart

On April 11, 1968, President Lyndon Johnson signed the last of the great civil rights bills. He'd been trying to move Fair Housing through Congress for two years, but the racial animus that infused the issue of residential desegregation — which corroded both Northern states as well as the Deep South — proved too profound.

In the end, Johnson managed to wrestle the Fair Housing Act onto his desk only because of the assassination of Martin Luther King and the ensuing conflagrations that swept America's cities. In the midst of national tragedy, Johnson managed to briefly overcome the toxic politics of racial prejudice in housing policy.

In his speech that afternoon, President Johnson placed the Fair Housing Act in the larger context of the 100-year struggle for freedom after the Emancipation Proclamation, and the other two civil rights victories of his term in office.

"[This law] proclaims that fair housing for all — all human beings who live in this country — is now a part of the American way of life," Johnson concluded.

But 50 years later, Johnson's victory lap reads as exceedingly premature, because only part of the Fair Housing Act was ever enforced. The law tries to both tackle explicit discrimination, like segregation in public housing and racial discrimination among mortgage lenders, and requires local jurisdictions to adopt local public policies to affirmatively pursue integration and fair housing. The first goal has been largely accomplished, but the second part, which would require the federal government to withhold funds from jurisdictions that reinforce segregated housing patterns, lacked follow-up.

Then in 2015, after years of stubbornly persistent segregation rates, HUD issued a new regulation to strengthen the 1968 law.

The Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule didn't give the federal agency any additional teeth and it didn't give local jurisdictions any additional funding. But it did provide new resources to allow local jurisdictions to follow through on their old obligations under the law, and then required them to document not only barriers to fair housing — which they'd always been supposed to provide to HUD — but their plans to overcome them.

Economic Segregation

Neighborhoods in the regions below (identified as "commuting" regions) have the greatest economic imbalance in the U.S.

1. New York

2. Bridgeport, Connecticut

3. Charlotte, North Carolina

4. San Jose, California

5. Kansas City, Missouri

6. Indianapolis

7. Philadelphia

8. Louisville, Kentucky

9. San Francisco

10. Santa Barbara, California

Source: Urban Institute

Still, some skeptics, who are otherwise supportive of the rule's goals, have critiqued AFFH as merely another round of bureaucratic paper pushing. (Actual opposition to the regulation has come from the conservative movement.) How is a problem as entrenched as residential segregation going to be overcome with yet another report?

The answer, in part, is that AFFH is meant to be a rallying action. Massive public participation requirements are baked into the rule and the reports can give local advocates, and HUD itself, metrics by which to measure progress made on promises by local politicians. And it gives those local governments a reason to act, a reason to change their ways.

"Local advocacy groups are faced with a lot of inertia in the institutions that are charged with doing the planning," says Megan Haberle, director of housing policy for the Poverty & Race Research Action Council. "The siloing of local government agencies is intense. Having a strong federal rule is really important to overcoming that."

Another argument for AFFH's relevancy could be found in the vitriol stirred in those who opposed it. Ben Carson as a presidential candidate warned that the rule was akin to "failed socialist experiments in this country," like public school busing. "Attention American Suburbs: You Have Just Been Annexed," a headline in the conservative magazine National Review blared.

It took almost a year for Carson, now HUD secretary, to move against the AFFH rule. But then in December 2017, he ordered the implementation of the regulation to be put on hold. His office argued that it placed too great a burden on local jurisdictions, a statement that civil rights and affordable housing groups vigorously dispute.

But despite Carson's action, there are still dozens of jurisdictions that followed through on its requirements. Major cities like Philadelphia (http://bit.ly/2EEyMw9) and Seattle (http://bit.ly/2ohPW7I) produced fair housing assessments, as did smaller counties and municipalities that receive Community Development Block Grants and other federal aid. Still others could choose to follow through without federal oversight.

Community advocates and public officials from those areas that have already compiled their reports say that no matter what the federal government does, the fair housing assessments have successfully shifted the policy conversation.

AFFH in Kansas City

The largest city in the Kansas City metropolitan region — Kansas City, Missouri — was one of the first jurisdictions to be asked to participate in the AFFH process. But they didn't want to do it alone, so city representatives reached out to 10 of the surrounding suburban and even exurban jurisdictions to see about forming a regional fair housing plan.

Five jurisdictions across two states signed on for the program: Blue Springs, Independence, and Kansas City in Missouri, and the city of Leavenworth and the unified Wyandotte County/Kansas City government in Kansas.

Numerous elements of civil society were included in the planning as well, including church groups and the local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Twenty-five public meetings were held across the five communities that participated in the AFFH plan. The final report (http://bit.ly/2CTMS74) was submitted to HUD in November 2016 and approved shortly thereafter.

The fair housing assessment outlined a series of issues that contributed to segregation in the region, from hyperlocal school districts that isolated racial minorities to a public transit system that failed to keep poorer urban neighborhoods connected to suburban job centers. ("41 percent of the region's residents have access to public transit, but transit systems only serve 9 percent of area jobs," it reads.)

It also noted that affordable housing was concentrated in low-income communities, with the exception of white and Latino Section 8 voucher holders who were more likely to have found their way to higher income census tracts ("providing evidence that race is a factor").

The Mid-American Regional Council, a nonprofit planning association for the metropolitan area, was retained to help steer the communities through the process. The organization's director of community development, Marlene Nagel, says that the public meetings proved especially productive because they weren't pitting residents against officials in an emotionally loaded meeting over a particular policy.

"It is new because it requires us to not only partner with regional entities but to do what we can to create affordable housing opportunities in some areas we had historically not thought of, quite frankly," said Stewart Bullington, deputy director of housing for Kansas City, Missouri, in an early 2017 interview. "It was a motivator. We never had anything written down like we do now, not only from the needs perspective but how we reach out on the communication and engagement side."

But in a critique of the AFFH process across the country, those who participated in the Kansas City planning process felt frustrated in any reform efforts by the ever-diminishing funding levels from the federal government. Even as local politicians and policy makers seemed more willing to address segregation, at least in participating communities, their ability to follow through seemed more limited than ever.

"I would say most [participants] felt like it was helpful to go through the process and that they learned some things about their communities," says Nagle of MARC. "But everyone says we don't have the resources to address the challenges [described] in the plan. I think that attitude hasn't changed, because they are all feeling like we are doing as much as we can do with the resources we have."

But Nagle and other stakeholders say that the AFFH process did help focus attention on an array of issues that hadn't received enough notice before — possibly preparing the way for future action.

Low-income people face challenges finding new housing because of a lack of availability of units in their price range, but poor people with disabilities can have additional problems, because of physical design issues like doorways that aren't broad enough to accommodate wheelchairs or entryways without ramps. Disability rights groups raised this issue during the region's AFFH process, and in 2018 dimensional standards beyond those specified in the American With Disabilities Act were recommended to the state housing agencies that distribute Low-Income Housing Tax Credits.

The fair housing rule set longer term efforts in motion as well. A new regional plan for the public transit system is under way, and many of the points highlighted by the AFFH process have been included, principally the focus on better connecting lower- income neighborhoods and suburban job hubs (like Amazon warehouses).

Right now, only five percent of jobs are transit accessible in the morning, dropping to three percent at night, for average workers within a 60-minute commute of their home.

Now neighboring Johnson County, where many of these suburban job centers exist, is considering pumping $300,000 into new bus routes to better connect inner-city neighborhoods with further-flung working-class jobs.

Another AFFH priority outlined in the Kansas City regional plan is mobility for Section 8 voucher holders, especially African-American families who face the most bias and live in the most highly segregated neighborhoods.

When Section 8 vouchers were first created in the 1970s, the hope was that they would give subsidized low-income households a chance to live in areas with better schools, better jobs, and less crime. But research has shown that, without outside assistance, it can be hard for people to find housing out-side of their own social networks and the neighborhood contexts that they know.

The Kansas City AFFH plan provides the framework for a proposal, based on a program in Baltimore, that would enable suburban and urban housing authorities to work together to encourage voucher holders to live in safer, better-served areas. A "regional housing locator" is also planned, to better pair interested families with neighborhoods.

Affordable Housing Mismatch

Data from Greater Kansas City, Missouri, shows that there is an imbalance between the availability of affordable housing and the number of low-income households that need it.

Source: Greater Kansas City, Missouri, Plan for Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing, Disproportionate Housing Needs Section.

Can fair housing succeed at the local level?

Like many of the dozens of other jurisdictions that completed the AFFH process before the current HUD leadership froze the rule, the municipalities in the Kansas City area say they plan to see their report through even without federal oversight.

"I don't think [the Trump administration's hold] will have any effect on the five cities that have decided to do the regional AFFH here," says Jennifer Tidwell, division manager for Kansas City's Department of Neighborhoods and Housing Services and former HUD administrator for the region. "We are moving forward on all our goals, so it won't affect our region at all."

But that's only true when it comes to the jurisdictions that self-selected into the AFFH process. They are likely those who need the most assistance with these issues, just as the public meetings predominantly attracted those who are already invested in questions of affordable housing and segregation.

So many of the goals in the report focus on attracting investment and affordable housing in low-income neighborhoods, rather than more opportunities in wealthier, and usually whiter, areas.

"While [community opposition] is an important contributing factor in inhibiting affordable housing in opportunity areas public input has indicated that the highest priorities should be given to improving neighborhoods where protected classes are concentrated, thus it has been given a medium priority," the report reads.

Land-use and zoning policy are given a medium priority as well, because "implementation of more inclusionary zoning and land use practices is mainly out of the hands of the communities participating in this regional AFFH" due to current state laws.

But even in a policy area that the plan marks as a priority, like the regional voucher system, the participants hesitate to devote their scant resources to a new and more expensive proposal that could limit the number of vouchers they can issue. Their waiting lists, after all, are already tens of thousands of people long — and pursuing a more integration-minded Section 8 strategy can be more expensive, meaning fewer people get help from vouchers overall.

"The challenge is that their resources are going in the wrong direction in terms of funding from HUD," says Nagle. "But they'd like to have the structure in place and an agreement between the housing authorities, so if the resources permit they could then implement it. But it's not quite as possible as they hope the future will allow it to be."

Is there a higher authority?

Part of the promise of the Fair Housing Act was that these kind of regional disparities could be overcome with the assistance of the federal government. If local jurisdictions resisted integration by, say, refusing to help Section 8 voucher holders relocate to whiter, wealthier locales, the feds could withhold infrastructure funding until they relented.

These threats were never followed through on after the early 1970s, but the Obama-era rule revived some of those promises. In theory, if jurisdictions didn't follow through on the promises outlined in the AFFH plans, HUD could withhold funds.

But few believed that HUD funds would get pulled, no matter who won the White House in 2016. In an environment where resources are limited, would a Democratic administration really be willing to withhold affordable housing resources to its constituent groups?

"We saw that when we first started, but it's quite a stick," said Bullington in an early 2017 interview. "We can't afford to not have our Community Development Block Grants and HOME funds flow. So it really didn't come up hardly at all over the production of this thing. It didn't hang over the plan's development as a kind of a threat or anything like that."

This is one of the essential dilemmas of fair housing advocacy and it is not limited to any region or state. As available resources shrink, the jurisdictions where low-income people live genuinely need affordable housing resources so they can satisfy some degree of need. But to meaningfully pursue desegregation, affordable housing dollars and efforts need to be expended in higher opportunity areas, too. It's a Catch-22, and HUD has largely avoided it by not focusing its shrinking resources on integration.

"I never thought that HUD would enforce anything anyway, because they never did," says John Logan, a professor at Brown University, who has studied segration. "Even under the Obama administration or if it had continued with the same people and the same progressive rhetoric, I had doubts they were actually going to do anything. They always had to be taken to court to push them into enforcing something."

The courts have paved the way. In Philadelphia in the 1970s, a judge forced a famously reactionary mayor to build public housing in a white neighborhood. In Yonkers, during the case dramatized in the HBO miniseries, Show Me a Hero, affordable housing units were built in white neighborhoods for a similar reason. Most recently, Dallas-based Inclusive Communities successfully sued the state over its propensity for building LIHTC units almost entirely in segregated, impoverished communities.

The courts have provided fair housing advocates succor under the Trump administration as well. Before freezing the AFFH rule, Carson ordered a halt to the Small Area Fair Market Rent program, which makes it easier for voucher holders to afford units in higher income areas. Antisegregation advocacy groups sued HUD over the delay and won.

Even an AFFH skeptic like Logan thinks it makes sense to try a similar tactic with AFFH.

"If I were active in an advocacy group, I would be loudly complaining about this change," says Logan. "Primarily for symbolic reasons. We've been pushing for things in the right direction and this is moving in the wrong direction."

Fair housing groups have considered suing HUD again over the delayed rule. But no matter what happens, the holdup on AFFH says a lot about the state of the Fair Housing Act.

Fifty years after President Johnson signed it, the last of the great civil rights laws requires a lawsuit if even the most liberal jurisdiction wants to fulfill its promise.

Jake Blumgart is a reporter with WHYY's PlanPhilly.

Resources

Show Me a Hero, a 2015 HBO miniseries about the true story of a mayor attempting to fulfill a court order to build low-income housing in white neighborhoods: http://itsh.bo/2okzRxX.

The New York Times revisits the Kerner Commission's 1968 assessment of inequality in the U.S.: http://nyti.ms/2oRqVAB

Chicago's Metropolitan Planning Council looks at the toll segregation takes on income, education, and lives: http://bit.ly/2tiqlRN

California Housing Crisis Jolts Legislature Into Action

By Josh Stephens

The Golden State is the country's most populous by far — and it has outsized affordable housing issues to match. Median monthly rates for two-bedroom rentals in many coastal cities are topping $2,000. Statewide, homes are selling for a median of $524,000 — with averages far higher near the coast. The Legislative Analyst's Office estimates that California must produce 100,000 more units — above its average of about 120,000 — annually to achieve affordability.

But cities have made that difficult. Wary of increased density, traffic, and demands on public services, residents of many California cities have advocated for restrictions on the type of development that could alleviate the crisis.

So the state legislature finally stepped in.

After years of relative inactivity, 130 housing-related bills were recently introduced. A package of 15 eventually passed in 2017, addressing both affordable (subsidized) housing and market-rate production, several of which require cities to facilitate housing production through reform of plans and zoning codes. The new laws fall into a few main categories:

FINANCING

Senate Bill No. 2 raises funds through a $75 transaction fee, while SB 3 places a measure on the 2018 statewide ballot to raise $4 billion.

ZONING AND STREAMLINING

The bill that got the most attention from planners, SB 35, requires cities to streamline the approvals process if it does not already meet certain housing goals. SB 540 creates "opportunity zones" for workforce housing, and SB 73 enables cities to conduct environmental reviews on entire districts so developers can develop conforming projects by right.

PRODUCTION GOALS

Every city in California must undergo a "Regional Housing Needs Assessment" and is required to absorb its fair share of the state's projected housing growth, accounting for these housing numbers in their planning documents.

AFFORDABLE HOUSING

Three bills further streamline local review processes to accommodate affordable housing development and give eligible developments more opportunity to challenge rejections.

"Each of the bills tackles a different piece of the housing process at the local level," says Sande George, a planning consultant and legislative advocate for the California Chapter of the American Planning Association.

Planners do not yet know how these new laws will relate to each other in practice. George says it's too soon to tell "whether or not we have the ability to actually put all of these bills together in some comprehensive, reasonable package at the local level that will work on the ground."

All told, these bills are the most significant attempt by the state to support subsidizing housing and lower regulatory bars impeding production of market-rate housing. But because legislation is an annual — and messy — process, and housing development a generational one, the results of these new laws are far from certain. Even the most optimistic proponents don't think they'll be enough.

Legislators are already trying to build on last year's momentum by introducing new legislation for consideration in 2018. State Senator Scott Weiner, architect of several of last year's bills, including SB 35, has doubled down. His SB 827 could be the most dramatic and, critics say, invasive housing law in recent memory. It would essentially require all cities with mass transit stops to permit high-density housing within a certain radius of those stops. Many housing advocates are cheering SB 827, but many city officials are wary of the loss of local control over approvals.

"To me they've gone past 'let's tinker with existing laws' to really get into eliminating the abilities of cities and counties to do planning and zoning as they have in the past," says George. "That's a big step."

Other topics legislators are expected to address include accessory dwelling units, further enforcement of RHNA, and tenant protections. Not on the table: funding. Governor Jerry Brown has indicated he prefers local streamlining over state expenditures.

By 2050, California's population is expected to rise another 10 million, to 50 million. If this new wave of legislation doesn't successfully produce more housing, we can only imagine where they're all going to live.

Josh Stephens is a contributing editor to the California Planning & Development Report.