Planning August/September 2018

The Silver Lining of Sea-Level Rise

Norfolk, Virginia, has significant challenges ahead — but also interesting business opportunities.

By Brian Barth

It's hard to remain a climate change skeptic when your street floods at high tide. In Norfolk, Virginia, says George Homewood, FAICP, the city's interim director of development (and former planning director), this has become part of the routine for some residents, impacting how they get to work or school. It's particularly a concern in high-poverty areas. Because of a combination of melting ice caps and localized sinking in this low-lying region along Chesapeake Bay — much of the city was built on coastal marsh — Norfolk has experienced more than 14 inches of relative sea-level rise since 1930, the highest rate on the East Coast.

"When the moon is full, there are streets in Norfolk where a kayak is the vehicle of choice at high tide." That's when skies are clear, says Homewood. "Add to that a summer rain bomb that dumps two inches of water in an hour and you begin to see why an awful lot of our population is entirely too familiar with flooding."

With climate change impacts already making themselves known in Norfolk, the city is taking a unique approach: If the problem is not going away, they are going to try to capitalize on what they learn from adapting to it.

A child plays outside the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk after a heavy rain last summer. Sunny-day flooding, associated with tides, not rain, is a regular occurrence. Photo by Skyler Ballard/Chesapeake Bay Program.

North America's 100 Resilient Cities

2013

Berkeley, California

Boulder, Colorado

El Paso, Texas

Los Angeles

Mexico City

New Orleans

New York City

Norfolk, Virginia

Oakland, California

San Francisco

2014

Boston

Chicago

Dallas

Juárez, Mexico

Montreal

Pittsburgh

San Juan, Puerto Rico

St. Louis

Tulsa, Oklahoma

2016

Atlanta

Calgary, Canada

Colima, Mexico

Greater Guadalajara Metropolitan Area, Mexico

Greater Miami

Honolulu

Louisville, Kentucky

Minneapolis

Nashville, Tennessee

Seattle

Toronto

Vancouver, Canada

Washington, D.C.

Climate change — an economic driver?

Much has been said about the negative economic impacts of a warming climate. But what if a city were to approach as an economic opportunity? Redevelopment, after all, goes hand in hand with natural disaster recovery.

A growing cadre of planners, designers, and economic development professionals — Homewood among them — believes the most effective way to deal with the impacts of climate change is to build an industry around it, and perhaps more importantly, an identity.

Norfolk lies at the center of Virginia's Hampton Roads region, an economically stagnant area where in some neighborhoods three out of four households are below the poverty line. The region has long been dependent on U.S. military installations for employment (Naval Station Norfolk is the world's largest naval base) and has struggled to diversify economically.

Since adopting its Vision 2100 planning framework in November 2016, Norfolk has made resilience part of its brand, billing itself as "the coastal community of the future." Named plan of the year by the Virginia Chapter of APA in 2017, Vision 2100 is wholly centered on sea-level rise as an organizing principle. The words in its preface are almost shockingly radical: Climate change is "not ... a dilemma, [it's] an opportunity — an opportunity to reimagine the city for the 22nd century."

Given the price tag of retrofitting the region to withstand storm surges and mitigate monthly tidal flooding, reimagining the problem as a solution doesn't seem far-fetched. It's more like a practical necessity.

While all for curbing emissions to prevent climate change from worsening, Homewood says he prefers to embrace the changes that it necessitates — since it is already here. Public safety, urban infrastructure, and economic prosperity are at risk otherwise. He hopes that by getting out ahead of the challenges, rather than putting off the inevitable, Norfolk will develop a valuable knowledge sector, one that can be exported, so to speak, as other places around the world are forced to confront environmental change.

Homewood envisions the region becoming the "Silicon Valley of sea-level rise." In other words, if you have an innovative idea about how cities can cope with climate change, he hopes you'll come to Norfolk to start your business.

"There is an entire innovation marketplace emerging around how to live with water and we think there needs to be a place with a focus on that," he says. "If you have an idea, come test it. We will help you push it out to other places. It's a win for the innovator and a win for the city of Norfolk."

David Waggonner, cofounder of the New Orleans architecture and planning firm Waggonner & Ball, which has consulted with cities around the world on their efforts to adapt to climate change, says Norfolk stands above the rest because its elected officials embrace the challenge.

"A lot of places don't want to deal with facts. But when you have the biggest navy base in the world, you don't have time for [denial]," Waggonner says. "Norfolk has become the leader because there is no debate there about sea-level rise. It's a matter of how fast, how much, and what are we going to do about it?"

Sea-Level Rise Threatens Norfolk's Defense Facilities

Norfolk is facing the fact that repeat flooding around the Hampton Roads area puts critical government and transportation infrastructure at risk. Not least is Naval Base Norfolk, the world's biggest naval base.

Map courtesy Waggonner & Ball.

Three-pronged approach

In 2013, Norfolk was one of 11 U.S. cities chosen in the first cohort of the 100 Resilient Cities network, a Rockefeller Foundation initiative that fosters innovation in resilience planning. One benefit of being included in this elite group is that the Foundation provides funding for a chief resilience officer.

Christine Morris, who was appointed Norfolk's CRO in 2014, breaks down climate resilience strategies into three arenas:

- Built environment: levees, berms, floodwalls, and other physical infrastructure designed to mitigate climate impact and protect urban development

- Government: initiatives such as buyouts of property deemed too costly to protect

- Social: interventions that improve a community's ability to withstand and recover from shocks

The built environment category received a major boost in 2016 when the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development awarded nearly $1 billion to 40 states, counties, and cities through its National Disaster Resilience Competition. Virginia received $120.5 million, most of which is earmarked for improvements in Norfolk's Chesterfield Heights and Grandy Village neighborhoods. This low-lying, low-income area along the Elizabeth River is accessible by only two roads. One is subject to storm surge flooding from the coast, and the other is subject to tidal, or "sunny-day," flooding.

Construction drawings are under way for a series of floodgates, seawalls, and berms designed to provide an additional three feet of flood protection along two miles of shoreline. All work must be completed by September 2022, per HUD guidelines.

Water that falls on land during massive storms complicates things.

"Creating a levee reduces the chance of the water coming onto the land during a tidal push, but then the problem is that you've created a bathtub, so the water can't drain out like it used to," explains Christine Morris.

To deal with water coming from every direction at once the city is looking to increase the landscape's storage capacity in any way they can, on both public and private property. These interventions include installing porous paving in parking areas, cisterns beneath roads, stormwater gardens in parks, bioswales along front yards, and rain barrels at every downspout.

"As the water moves toward the river, we want to slow it down so it doesn't go there all at once. That's what causes flooding," Morris says.

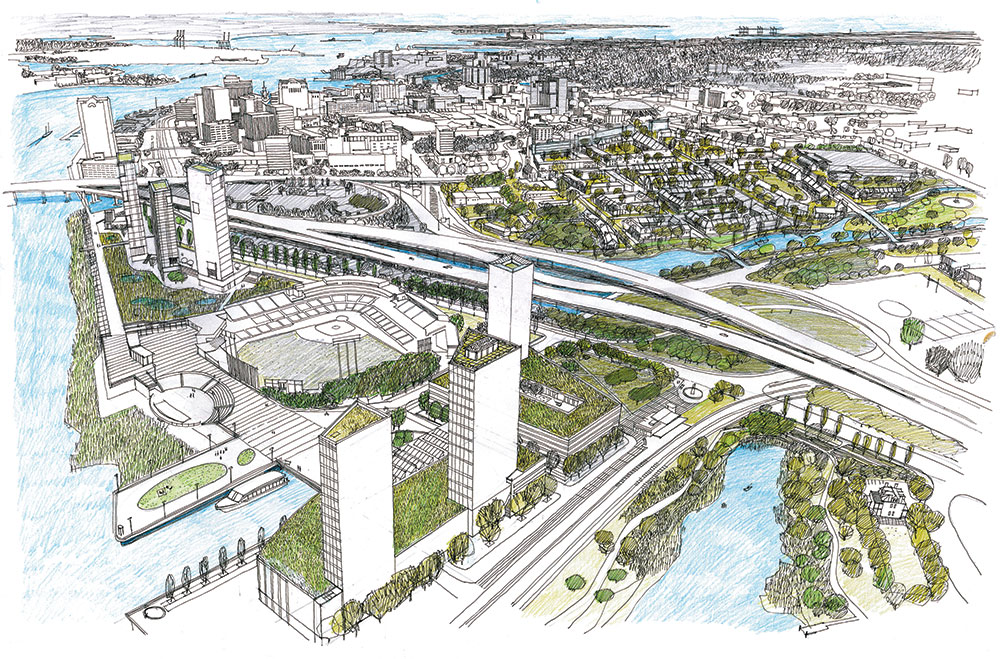

During a series of Dutch Dialogues Virginia charrettes, Waggonner & Ball created a visionfor Harbor Park and St. Paul's neighborhood illustrating potential waterfront development integrated with multifunctional, coastal flood defense. The plan calls for public housing redevelopment around green infrastructure streets and the reestablishment of Newton's Creek beyond. Rendering courtesy Waggonner & Bell.

ROI on resiliency

Norfolk's economic development angle in planning for sea-level rise is wise. As it turns out, preparing for climate change has become a big business.

According to the Climate Change Business Journal, the global climate change industry — encompassing everything from renewable energy and electric cars to green building and climate-related insurance — is already worth $1.5 trillion. A subset of that is the $2 billion market for what the publication terms "Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience," which includes the engineering of "preventive" structures, along with "risk science, modeling, and planning work."

Louisiana provides a prime example of how climate change is already shaping local economies. According to a 2016 report by the Restore the Mississippi River Delta Coalition, the water management industry (building levees, reconstructing wetlands to deter storm surge and the like) has eclipsed the oil and gas industry as the biggest economic driver in the region around New Orleans.

Like Hampton Roads, Cajun country, which suffers the highest rate of relative sea-level rise on the planet, has much to lose from inaction: Already an estimated 2,800 square miles of coast is expected to be lost over the next 40 years and about 27,000 buildings will need to be flood-proofed or abandoned.

David Waggonner notes that Homewood wasn't the first person to come up with the idea of exporting expertise to deal with sea-level rise. Dutch planners and designers descended on Louisiana soon after Katrina's waters receded. With much of the Netherlands sitting at or below sea level, they long ago found themselves in the position New Orleans and Norfolk are in today.

In cooperation with the Dutch Embassy and APA, Waggonner helped to organize a series of conferences called Dutch Dialogues in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. They were dedicated to changing how the city fabric related to water, namely to integrate it and celebrate it as an amenity rather than rely solely on levees, floodwalls, and massive pumps to keep it at bay. Now Dutch Dialogues Virginia is taking place in Hampton Roads.

"In order to keep disinvestment from being widespread ... we have to find a way to make it safer and more attractive so that people won't leave," says Waggonner, who envisions beautiful stormwater canals, such as those found in Amsterdam, as the skeleton around which future development in New Orleans and other low-lying cities could be clustered. And, like any attractive landscape features built with public funds, something that will lure real estate investment.

"It's a question of making something good come from something bad," he says.

Waggonner suggests tax increment financing as a mechanism to fund resilience infrastructure and to capture the value it creates — waterfront properties demand higher prices.

Norfolk's New Resilience-Quotient Zoning

The unanimously approved zoning changes include a points-based matrix that allows developers to choose from a menu of features to reach project approval. Points are assessed for nonresidential and residential development in three categories (see a selection below).

| Category | Resilient Development Activity | Points Earned |

|---|---|---|

| Risk Reduction | Construct building to withstand 110-mile wind load. | 2.00 |

| Elevate the ground story and electrical and mechanical equipment three feet above grade. | 1.00, plus 0.50 per foot above 3 feet | |

| Install a generator for power generation for critical operations in the event of power failure. | 0.50 | |

| Stormwater management | Install a green roof on at least 50 percent of the total roof area. | 2.00 |

| Preserve large, non-exotic trees on site. | 0.10 per tree preserved | |

| Energy resilience | Generate at least 75 percent of the electricity from solar and/or wind energy sources. | 3.00 |

| Install a cool roof on at least 50 percent of the total roof area of the development. | 1.50 | |

| Provide electric vehicle level 2 charging stations for users of the project. | 0.25 for every two stations | |

| Use vegetation or vegetated structures to shade each dwelling's HVAC unit. | 0.25 |

To view the entire document go to https://bit.ly/2KvEIK0.

Zoning for sea-level rise

Norfolk lacks funding to implement flood protection infrastructure across all 144 miles of the city's coastline all at once, so they're building it in high-priority areas first while complementing it with a variety of low-cost interventions elsewhere. For example, the Neighbors Helping Neighbors program, aimed at residents of Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority apartments, gathers community members together to learn about disaster readiness, neighborhood safety, and first aid.

A far more complex initiative (though still much cheaper than armoring the coastline) is the revised zoning code that was adopted unanimously by the city council in January. The goal, says Homewood, was to create "the most resilient zoning ordinance in America ... in a city that is 97 percent developed with a middling construction market."

The new zoning code requires a three-foot "free-board" (elevation of the ground floor above grade) and pervious parking surfaces in the most floodprone areas. It also incentivizes high-density development in flood-safe upland areas by streamlining the approvals process.

The zoning code also introduces a concept called the "resilience quotient," a points-based matrix that allows developers to choose from a menu of building features — ranging from green roofs to backup power systems — to reach a threshold required for project approval.

The climate-equity question

While many cities have resiliency officers and climate change task forces, Norfolk is a rare example where the urgency of planning for large-scale disruption seems to be stitched into almost every aspect of municipal management. This is plainly evident in Vision 2100, the city's effort to integrate resilience thinking in a new comprehensive plan, which considered an 80-plus-year planning horizon rather than the conventional 20 to 30 years.

Morris says it's important to note that resilience is not just about stormwater, seawalls, and emergency management plans. It's about the ability to recover from any shock — natural, social, or economic — which in the end largely boils down to the overall health and prosperity of the community. Because vulnerability to shocks is highly correlated with impoverished neighborhoods, Vision 2100 includes a focus on deconcentrating poverty in Norfolk by encouraging mixed income development.

With a Retain Your Rain grant from the Norfolk Office of Resilience, Eggleston, a nonprofit that provides opportunities to people with disabilities, built a water catchment system that collects and stores water for community gardening. Photo courtesy Andrew Cooper, City of Norfolk.

But inevitably, wherever redevelopment occurs, the forces of gentrification are in play. That's an issue in New Orleans, and in Norfolk, too. There, subsidized housing in the Tidewater Gardens neighborhood is slated to be torn down, in part because it is one of the most flood-prone parts of the city and in part because of its state of disrepair.

The plan is to replace it with a mixed use, mixed-income community with flood mitigation infrastructure built in.

The plan has been met with some skepticism from low-income residents wary of being priced out, a worry that Homewood has worked to assuage. The St. Paul's Area People First Transformation Plan, which governs redevelopment in this part of town, is all about "working toward inclusive economic growth so that the economy of the city works for everyone," he says.

The city is approaching this equity problem from other angles, such as Bank On Norfolk, a partnership with local financial institutions in which residents take free classes on money management, debt reduction, and improving credit scores.

Much of the city's resilience strategy is comprised of simple, low-cost efforts like this, which are not uncommon in other places in the U.S., but not necessarily integrated within a resilience lens.

Morris cites another example of the city's resilience strategy that would seem to have little to do with climate change: Norfolk is putting some of its resilience funding toward off-street pedestrian pathways.

"Connectivity, whether to neighbors so that you can make plans together to get out of harm's way, or to the amenities of the community," is a significant resilience indicator, says Morris. "Resilience is about having the ability to work with each other so that you can reduce the risk of any potential shock."

Jared Genova, a former 100 Resilient Cities fellow who until recently served as the resilience planning and strategy manager for New Orleans, sums it up best: "It turns out resilience is actually just good planning."

Brian Barth is a freelance journalist with a background in environmental planning.

Resources

The Union of Concerned Scientists identifies threats to U.S. coastal communities and offers a wealth of maps and analysis. https://bit.ly/2ubkUCZ

PBS News Hour's Student Reporting Labs talks to kids in Newport News about the environmental forces changing their hometown. https://vimeo.com/264665600