Planning July 2018

Retail Realities

Rebuilding economic resiliency as brick and mortar goes to pieces.

By Jeffrey Spivak

For years the Oakland, California, suburb of Pittsburg followed a traditional playbook in its efforts to revitalize its downtown: It tried to lure retailers. First, it focused on trying to replace the JCPenney and Montgomery Ward department stores that closed. That didn't work out.

Later, the city of 70,000 turned its attention to filling the smaller retail spaces along its main drag. Despite that effort, the downtown strip remains pockmarked with vacancies.

Now, with a major retail disruption sweeping the country and record numbers of store closings, Pittsburg's planning commission and staff decided to try something different. Earlier this year, the city approved revisions to its retail-only zoning classifications to allow a variety of new uses in downtown's ground-floor, street-fronting spaces. The new uses range from offices to fitness facilities. The idea is to liven up the street with some pedestrian activity without relying on retail. One formerly vacant retail space has been replaced by a karate studio.

"We're trying to open downtown up to other types of businesses that will get feet on the ground and turn it into a vibrant environment in a different way," says Kristin Pollot, AICP, Pittsburg's planning manager. "Of course, we always want retail. But we've come to the realization that we're not going to get a lot of it anymore."

Cities large and small across the U.S. are beginning to come to that same realization.

2017 Retail Store Closings

1,470: Radio Shack

700: Payless ShoeSource

358: Sears and Kmart

190: GameStop

Source: FGRT

The goods-based consumer retail industry is undergoing a seismic shift and transformation. Bigname retailers are declaring bankruptcy and closing hundreds of stores, as online purchases grow and American buying habits change. Last year even set a record for announced store closings. This is having a trickle-down effect on communities, as some see their brick-and-mortar retail bases slowly eroding, with impacts felt in shopping centers and along traditional Main Streets.

Planners in some cities and counties are taking proactive approaches to the shifting retail landscape. They're commissioning studies of the marketplace and developing new strategies to maintain and foster better retail environments.

"There's a lot of upheaval going on in the retail industry, so we want to get ahead of that," says Rick Liu, AICP, an economic and development specialist with the Montgomery Country, Maryland, planning department outside Washington, D.C.

Liu's department is working to adjust zoning regulations to allow different nonretail uses in traditionally retail-oriented ground-floor storefront spaces. The Denver suburb of Aurora has tax incentives for sales-producing businesses in new retail development projects. And the town of Lake Park, Florida, outside West Palm Beach, is working with a developer to expand a shopping center into a live-work- shop mixed use center.

With just 3,000 square feet, Nordstrom Local in West Hollywood, California, has no inventory; instead, it's billed as a service-focused concept store, where customers can meet with personal stylists, pick up items ordered online, and have their clothing purchases altered. Photo courtesy Nordstrom.

Then there's Madison, Wisconsin, which has embarked on a menu of strategies.

Madison's most well-known retail corridor is State Street downtown, which spans several blocks between the University of Wisconsin campus and the state capitol. But in the last few years, prominent proprietors of bicycles, shoes, and healing arts establishments closed up shop. This prompted the city's planning and economic development department to embark on a retail assessment in 2016.

The study found the proportion of retail- and service-oriented shops among State Street storefronts had dropped in the last couple of decades from more than 70 percent in 1989 to 51 percent in 2014. This year, it's believed that proportion has dropped below 50 percent, as restaurants and bars continue making inroads.

"We're at a tipping point," says Rebecca Cnare, an urban design planner with the city who performed some of the research. "We're not interested in becoming a nighttime-only district."

During the past year, a partnership of the planning division and other city agencies has employed several tactics to support downtown's retail marketplace.

These include allowing more signage outside storefronts; adding new bike racks, benches, and other street furniture; holding special retail-oriented events like extended nighttime hours; and even creating a new business incubator to foster small businesses, including retail.

"I'm hopeful we can keep the retail balance we have now and maybe grow it where possible," Cnare says. "We need State Street to remain a retail destination."

Ultimately, the retail challenge is important for planners to monitor and counter, because a variety of signs point to the current retail shifts continuing and even accelerating in coming years.

Flexibility in Montgomery County

Montgomery County, Maryland, had zoning flexibility in mind last December when it approved the Grosvenor-Strathmore Metro Area Minor Master Plan. A 2017 study showed that retail works best in nodes or districts where existing shopping is clustered — meaning new buildings outside those districts shouldn't be required to have ground-floor retail.

The first project under this new plan, Strathmore Square, will be a transit-oriented development above the Grosvenor-Strathmore Metro station and between two retail hubs. Strathmore Square will include a mix of residential buildings and heights, small-scale retail, public art and performance space, greenspace, and bike paths.

Drawing courtesy Montgomery County.

Photo courtesy Montgomery County.

Last summer the developer, Fivesquares, repurposed old Metro rail cars as "stores" for small, local businesses in a popup vendor plaza. The initiative won the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority's 2018 Gold Sustainability Award for business practices.

Drawing courtesy Montgomery County.

Photo courtesy Montgomery County.

National retail upheaval

Recent headlines depict an industry on the brink of collapse. "The Great Retail Apocalypse," screamed The Atlantic. "America's 'Retail Apocalypse' Is Really Just Beginning," declared Bloomberg. "Is 2017 the death of retail as we know it?" asked USA Today. "Retailers on the 2018 Death Watch," proclaimed The Motley Fool. It's all related to a historic deluge of brand-name retail corporate bankruptcies and store closings.

It's all related to a historic deluge of brand-name retail corporate Bankruptcy filings just last year included Toys "R" Us, RadioShack, Payless ShoeSource, Goldman's department store, teen clothier Rue21, and several more. Meanwhile, since the start of 2017, more than two dozen retail companies have announced plans to close at least 100 stores each, from Walgreens (which now includes Rite Aid) and Sears to GameStop and Signet, the parent company of Zales and Kay Jewelers.

State Street in Madison, Wisconsin, has always been known for its retail offerings. Over the past few years, though, many retail and service businesses moved out and bars and restaurants took their place. The city is trying various approaches to keep the retail balance. Photo by Csfotoimages/iStock.

New York-based retail consultant Fung Global Retail & Technology, now known as Coresight Research, tracked 7,066 store closings announced last year in the U.S. Some publications put the figure above 8,000. Either way, 2017's tally was more than three times bigger than 2016's total and eclipsed Fung's previous high-water mark for store-closing announcements — 6,164 in 2008, at the onset of the last recession. And according to Coresight, 2018 through April was already surpassing 2017's pace of announced closings.

Curiously, this tidal wave of negative news has been occurring against a backdrop of several positive trends — the U.S. economy has been strengthening, consumer confidence is high, total retail sales continue to grow at two to three percent per year, and shopping mall occupancy rates remain steady and solid, according to the retail industry's National Retail Federation and the International Council of Shopping Centers.

Based on this view of the retail environment, Mark Mathews, the Retail Federation's vice president of research development and industry analysis, even claims: "Things are going reasonably well."

So what's going on?

"The U.S. retail sector is overstored and out of step in an era of e-commerce," Goldman Sachs analyst Matthew Fassler wrote in an industry brief last year. "But retail is not dead; it is changing."

A variety of factors are conspiring at once to change the face of American shopping. First and foremost, more people are making purchases online instead of inside stores, although e-commerce still makes up less than 10 percent of U.S. retail sales. In addition, consumers are increasingly gravitating to discount stores and prices, and spending habits are shifting from buying "things" to buying experiences: eating out, traveling. In 2016, for the first time ever, Americans spent more money at restaurants and bars than at grocery stores.

Meanwhile, the U.S. retail landscape is severely overbuilt. Financial services firm Cowen Inc. has noted the U.S. already has 40 percent more shopping space per capita than Canada and five times more than the UK. So some retail retrenchment is almost inevitable.

As a result, retail bankruptcies and store closings are concentrated in certain sectors, notably big-box electronics stores, apparel-based department stores, and clothing and footwear specialty stores, among others. These have been hard hit by online shopping. Conversely, some other major retail sectors, like grocers, warehouse clubs, and sporting goods stores, are actually growing and adding physical locations. The Dollar General discount chain announced more than 1,000 store openings last year.

"What you're seeing today is the end of the department store era," says Nick Egelanian, president and founder of SiteWorks Retail Real Estate Services, a consulting firm in Maryland.

E-Commerce Is Driving National Retail Growth

40%

The amount of retail growth from retailers with no physical presence, 2014–2016.

$300 billion

The increase in online sales between 2006 and 2016.

25%

The percentage of books and gifts purchased online.

334%

Percent change in e-commerce retail jobs over the past 15 years.

Sources: San Francisco Retail Study, The New York Times.

How planners are responding

Whether what's happening is a retail shakeout or simply shifting tastes, the changing retail landscape is getting the attention of planners. Communities like New York City, San Francisco, Montgomery County, Maryland, and Madison, Wisconsin, have completed retail studies to identify their current gaps and possible vulnerabilities. These studies identified several tools and strategies for planners — and their communities — to address a potentially shrinking brick-and-mortar retail marketplace, including:

- New regulations requiring commercial property owners to register vacant or abandoned storefronts, so cities can more easily track and contend with them

- Financial incentive programs like tax breaks or low-interest loans, specifically targeted to attract certain types of retail in certain areas. Grocers, for example, in neighborhoods lacking supermarket access

- Zoning restrictions on chain stores and big-box retailers, or ordinances requiring a certain mix of locally based retailers, as ways to encourage a balance of homegrown shops and level the playing field for them

- Reducing or eliminating the mandates for ground-floor retail in new multistory developments, as such mandates may have a role in generating an over-supply of retail

- Prioritizing and supporting the redevelopment of aging and outdated retail spaces

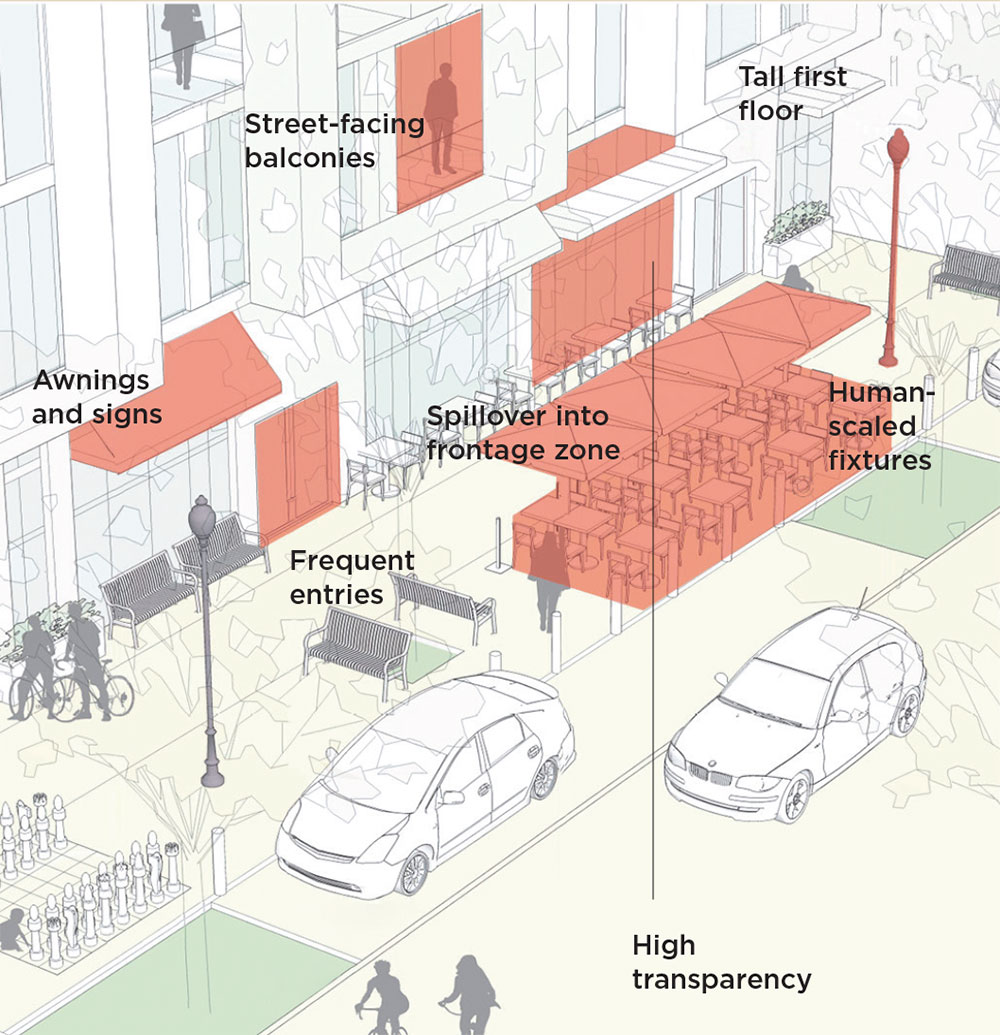

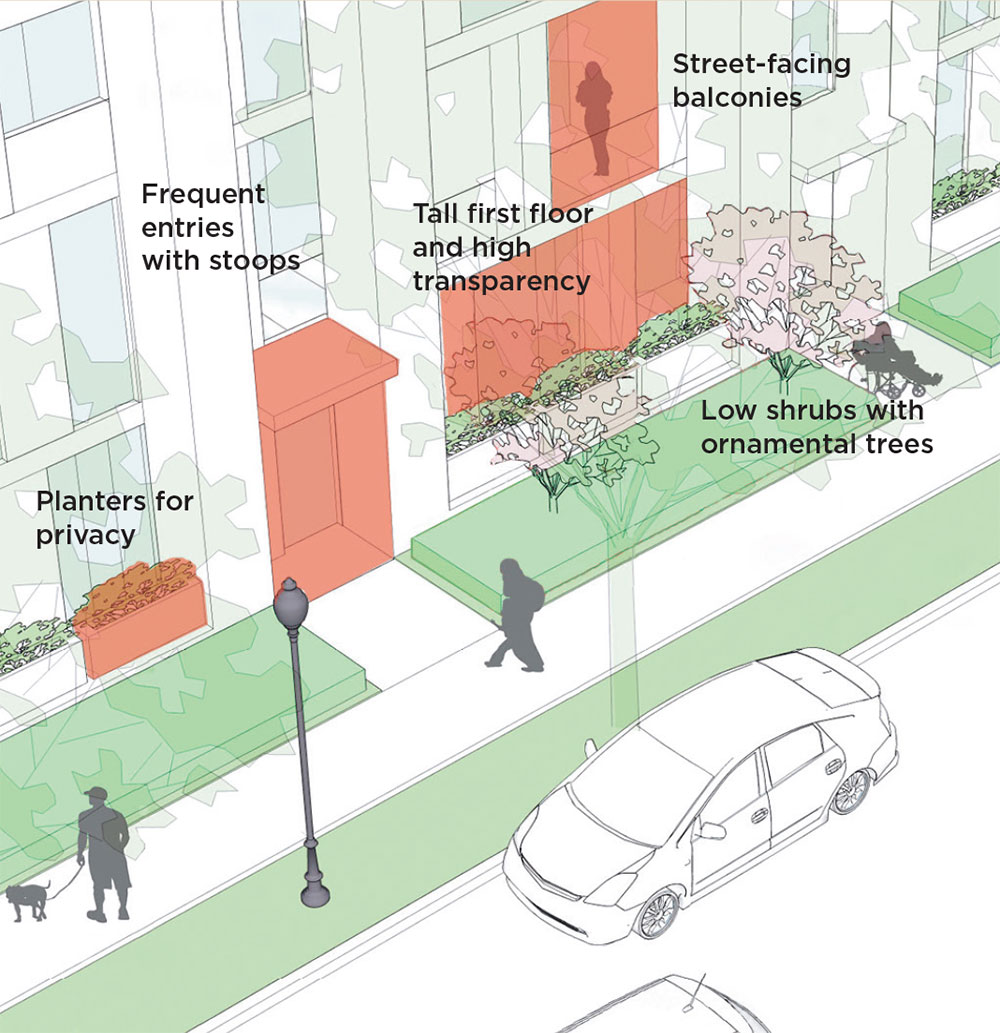

Overall, one theme in particular has emerged as a guiding principle for planners as they contemplate their communities' retail futures. That theme is flexibility. It means opening up retail-type spaces or districts to different uses: restaurants, service-oriented businesses, even storefront offices.

In San Francisco, a city known for complicated and detailed property restrictions, a study of the retail environment earlier this year prompted planning commission discussions and a planning department recommendation to explore ways to allow more flexible or alternative business uses in some neighborhoods facing vacancy concerns. One example would be combining multiple uses within one storefront, like a coworking space added to a retail shop.

"Our role is to constantly evaluate zoning code and use limitations to make sure we're adapting the code to the changing times," says Audrey Butkus, a senior planner in San Francisco's department.

Montgomery County is a little further along in allowing flexibility. Its 2017 county retail study determined that retail worked best in nodes or districts where existing shopping options are clustered. For county planners, that means new buildings outside such districts should not necessarily be required to have ground-floor retail.

So last fall the county reviewed a massive development plan with new residential towers located in an area between two retail hubs. Before the plan was eventually approved, planners worked with the developer on ways to activate the towers' street-level spaces, but with limited retail. One idea they settled on was providing classroom spaces affiliated with a nearby arts and music center. The development, called Strathmore Square, is scheduled to begin construction next year.

"The watchword is flexibility," says Gwen Wright, director of the county's planning department. "That is, flexible in terms of where we encourage retail and where existing retail can be augmented by adding new uses that can support that retail. The goal is to still activate the pedestrian realm without putting retail everywhere."

Adapting in the future

Even with the accelerating shifts, brick-and-mortar retail is not going away. It still accounts for some 90 percent of total retail sales. So retailers are attempting to adapt and modernize. A number are experimenting with different formats and concepts to draw in customers in new ways.

Some companies are trying smaller footprints. Urban Outfitters opened a showroom-type shop in Los Angeles that displayed apartment furniture shoppers could order online at kiosks. Former big-box retailer Circuit City intends to come back from bankruptcy with small-scale versions of its former stores, also kiosks. And Dollar General's expansion plan includes a small-format concept called DGX for urban settings.

Other merchants are embracing so-called "experiential retailing," in which store visits offer a distinctive experience. Nordstrom opened a "concept store" in an LA suburb that is stocked not with inventory, but stylists who can help customers put together ensembles using tablets. Sporting goods stores feature golf-stroke simulators. Cookware stores teach cooking classes. Upscale grocers serve beer and wine at in-store bars.

"Those are the retail environments we see with staying power," says Jaclyn Tidwell, policy director for SPUR, a Bay Area planning association that conducted a forum in San Jose earlier this year on the future of retail.

While physical stores may not be going away, there will likely be fewer of them, which could have some real consequences for planners and their communities in the future.

A report last year from the CoStar Group, a commercial real estate information company, estimated that one billion square feet of retail space would need to be demolished or repurposed to move the U. S. retail market into a balanced amount of supply and demand. Older, less-vibrant Class B and C shopping centers are considered the most vulnerable, along with retail sectors most impacted by online shopping, such as apparel and department stores.

Similarly, planners with the Urban Mobility Research Center at the Ohio State University in Columbus developed a model that predicts future retail disruption from such factors as the current overbuilt marketplace, the rise of autonomous vehicles, and the growth of home delivery. The model shows that suburban strip malls and big-box stores will be impacted the most; some are likely to become vacant wastelands. Others will find alternative uses, such as big-box buildings converted to warehouses.

The lesson for planners is to prepare for these continued shifts.

"We can see where a lot of this is going, and planners can help guide it," says Rick Stein, AICP, founding member of the urban research center and owner of a Columbus-based planning consultancy, the Urban Decision Group.

But there is no silver bullet or one-size-fits-all approach to supporting and sustaining retail development. Different communities can — and have — taken different planning approaches.

When a development company proposed expanding a grocery-anchored strip center in the south Florida town of Lake Park, city leaders and planners convinced the company to consider alternatives in today's retail environment. A new site plan this year envisions a mixed use center with retail complemented by second-story apartments and other uses in additional buildings like offices, restaurants, and services like a gym.

"We need to complement the retail so it can thrive in a more energized environment," says Lake Park Town Manager John D'Agostino.

Meanwhile, Aurora has created its own planning staff position devoted to retail development. In a city where retail-related taxes provide more than half its revenue, this manager-level position helps developers identify sites and navigate the permitting process, among other things. The current retail manager, Tim Gonerka, has also worked with developers to ensure their projects incorporate plenty of sales-producing retailers rather than settle for service businesses.

"We've moved from a passive city to a proactive city on this issue," Gonerka says.

Jeffrey Spivak, a market research director in suburban Kansas City, Missouri, is an award-winning writer specializing in real estate planning, development and demographic trends.

Resources

Montgomery County, Maryland, Retail Market Strategy Study: http://bit.ly/2rYxP9J.

International Council of Shopping Centers' research on the importance of physical stores: http://bit.ly/2wZYt6G.

Empty Stores Leave Big Budget Holes

Retail industry upheaval isn't only creating challenges for planners.

"The closings of retail stores have a definite negative impact on state and local governments," says Lucy Dadayan, who tracks tax revenues as a senior policy analyst at the Rockefeller Institute of Government, the public policy research arm of the State University of New York.

Lower sales in physical stores are causing some retailers to pursue property reassessments and lower taxes. Big-box retailers like Menards, Walgreen's, and Walmart are increasingly challenging property appraisals, arguing their buildings shouldn't be valued based on construction costs or commercial activities but as empty buildings available for a future buyer.

This argument is known as "dark store theory," and successful challenges have cut some big-box property assessments — and taxes — by more than half.

Meanwhile, record numbers of store closings and the escalating shift to online retail are taking bites out of state and local sales tax revenues. Sales tax generally accounts for around 30 percent of state government revenue and 10 percent of city government revenue, according to the Rockefeller Institute. But in recent years, sales tax collection has weakened: The year-over-year growth rate averaged 2.5 percent in 2016–17, half the five percent rate in 2014–15.

The Better Government Association, a nonprofit watchdog group, estimated that Macy's and Kmart closings in the small town of Alton, Illinois, last year would leave a $240,000 budget hole — the size of the town's capital budget in 2016. Nationwide, the Government Accountability Office estimated that state and local governments lost $8 to $13 billion in sales taxes last year because of limited laws on online sales tax collections.

But relief could be on the horizon. The U.S. Supreme Court is considering a case involving South Dakota's attempts to collect sales taxes on purchases made by out-of-state sellers. South Dakota v. Wayfair will essentially review the court's 1992 decision in Quill v. North Dakota that ruled a state or locality could not collect sales taxes from a vendor unless that vendor had a "physical presence" in the state. In agreeing to take the South Dakota case, the court indicated it was open to reversing or altering the Quill decision (the decision was expected in late June).

"It will be a big deal for governments," Dadayan says. "We're going to face a long-term crisis if nothing is done."