Planning March 2018

The Geography of Loss

GIS and planning have joined the fight against the opioid epidemic.

By Brian Barth

On September 13, 2007, J.T. Lindemann died of a drug overdose in his apartment in Laramie, Wyoming, after a long struggle with opiates. The 22-year-old musician had been in and out of substance abuse treatment for years, but never fully recovered. His older brother, Jeremiah Lindemann, a geographer and GIS specialist, didn't want J.T. to remain another anonymous data point.

"There is such a stigma," he says. "People tend to think it's really awful people using drugs, that they make their choice and deserve the consequences."

Lindemann wanted others to understand that drug addiction can happen to anyone, regardless of their personal character or socioeconomic background. For years, though, he felt uncomfortable sharing his brother's story with friends and coworkers, much less publicly — until the so-called opioid epidemic became a staple on the nightly news.

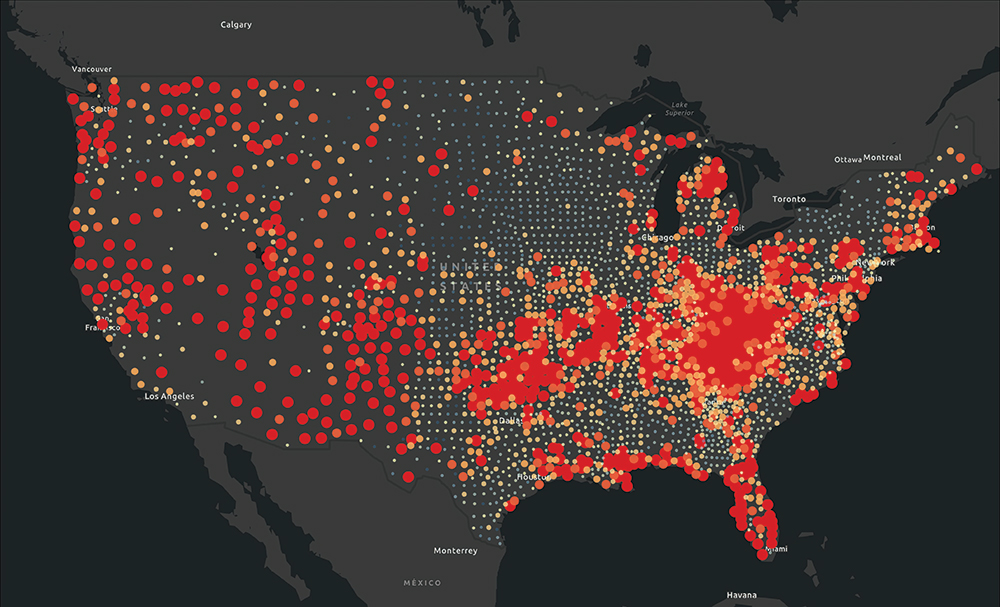

In the past five years, overdose deaths involving opioids have skyrocketed exponentially in the U.S.: In 2013, around 25,000 were reported; in 2016, more than 60,000. Today, opioids are the leading cause of death for Americans under 50.

Propelled by grief, Lindemann sought action. A solutions engineer at Esri by day, at night Lindemann began developing Celebrating Lost Loved Ones, a mapping application that allows those affected by opioid addiction to share their stories. J.T.'s photo was the first on the map when the site went live in 2015 (crowdsourcing began in 2016).

Lindemann's project grew to include more than 1,300 stories that paint a personalized picture of the problem in a way that jaw-dropping statistics cannot. It's also led to more maps: In 2017, Esri published a series of GIS templates that allow communities to track and communicate data related to opiate use, and Lindemann is even working on a crowdsourced map of employers open to hiring people in recovery. Local governments, including in Oakland County, Michigan, and several in the Denver area, are also beginning to use maps to educate residents about the severity of the problem and connect people with nearby substance abuse services.

"Mapping has become my way of advocacy," says Lindemann.

It's also helped spark a nationwide conversation about the role of land-use policy and community design in addressing the opioid crisis. In the haste to deal with the short-term impacts of the opioid crisis, Lindemann says, there is rarely a single entity in each city, town, or county taking a holistic, evidence-based, long-term view — but planners could be the ones to connect those big-picture dots.

Opioid Deaths in the U.S.: Red dots represent areas where the drug overdose death rate is very high — more than 20 deaths per 100,000 population. The national average of 12–14 deaths per 100,000 is in yellow and the areas with the lowest number of deaths, (0–2) are shown in blue. Source: Esri.

Celebrating Lost Loved Ones

J.T. Lindemann, 1985–2007

The National Safety Council recently adopted the interactive map Jeremiah Lindemann started after his brother J.T. died of an opioid overdose. Since 2016, when the crowdsourced map launched, it has gathered more than 1,300 memorials from around the country: losttoopioids.nsc.org

First steps

Planners are starting to heed the call, albeit slowly, says Elizabeth Hartig, a former project coordinator for APA's Planning and Community Health Center. The center helped shepherd a national movement to integrate planning and public health in recent years, one that has largely focused on increasing opportunities for physical activity and access to healthy foods in urban areas. Today, Hartig says, the opioid crisis is becoming a top priority.

"We are moving beyond the healthy eating and active living space and trying to think about the planning skills that can address the substance abuse issue on a longer-term time horizon," says Hartig. "The epidemic is everywhere and all-consuming — people are in crisis mode — so it's unsurprising that we aren't yet focused on how it relates to the built environment."

She suggests reframing the problem as a mental health issue, in keeping with what substance abuse experts widely agree is at the root of any drug problem. Encouraging safe communities, affordable housing, and stable livelihoods are clearly supportive to psychological well-being. But drilling down beyond those basic policy goals to find the specific levers within the built environment that cause individuals, or entire communities, to become vulnerable to substance abuse is another story.

To that end, the Planning and Community Health Center offered "Introduction to the Opioid Epidemic" in January, the first of three webinars on the topic they will present in 2018.

In the meantime, staff work the phones, hosting regular conference calls with APA chapter representatives throughout the country. Together, they are hoping to hash out a planning framework to address substance abuse issues.

Justin Dula, AICP, the manager of community and regional planning for Delaware County, Pennsylvania, regularly participates in those calls. He says there is no shortage of interest. Dula recently sent a survey to the planning directors of every county in Pennsylvania. Among other questions, they were asked which public health issues they considered most pressing. Substance abuse was the number one response. They were also asked to rank which health issues they felt best equipped to change. In that category, substance abuse ranked near the bottom.

"This is a huge need that planners want to be involved with," says Dula, "but the discussion of what the right tools are is just beginning."

Until recently, Dula says the priority among Pennsylvania policy makers was making sure naloxone, an overdose antidote, was distributed to every police department, and that a system was in place to monitor opioid prescriptions. "Now we can start to think longer term," he says.

As a first step, he suggests planners establish partnerships with their local health care providers — not only to tackle this problem but also to become engaged with the public health system in general.

"A lot of times health professionals don't have connections with elected officials or municipal managers. So that's a way that we can start to be part of the conversation," he says.

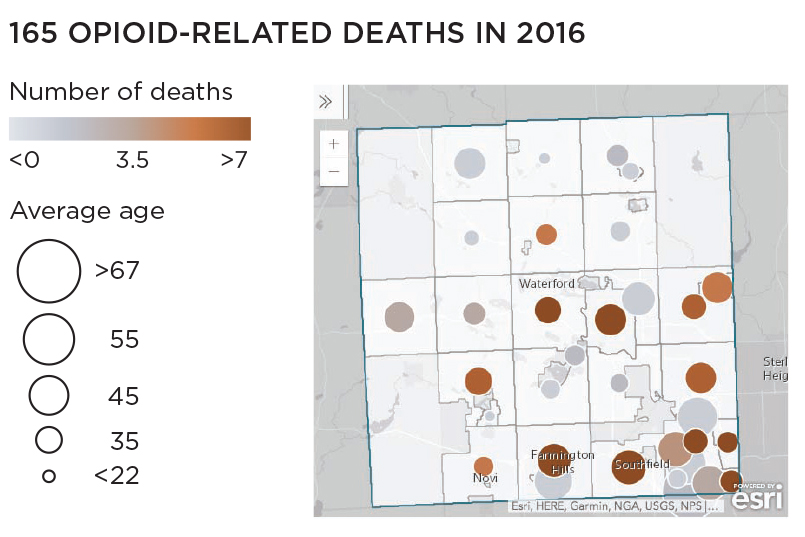

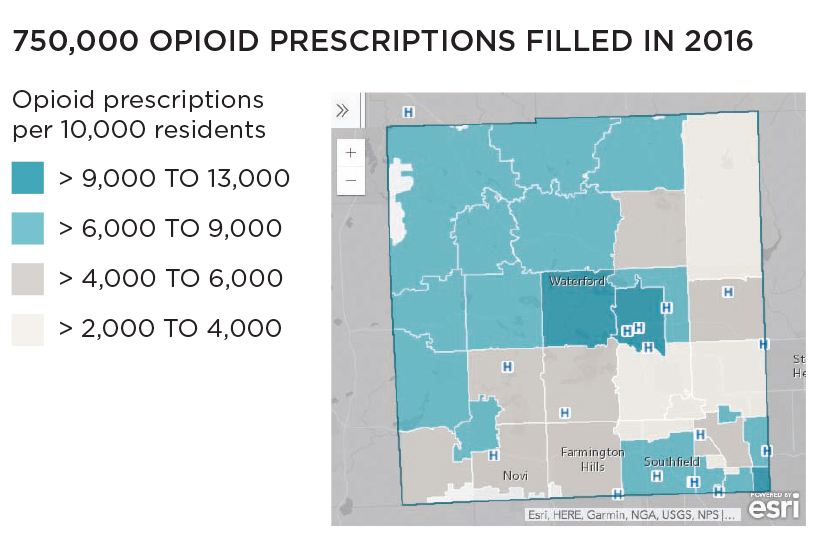

Fighting Back in Michigan

Oakland County, Michigan (pop. 1.2 million), northwest of Detroit, filed a lawsuit in October 2017 with Wayne County against drug manufacturers and distributors, alleging deceptive marketing and sales of opioids leading to excessive prescriptions, addiction, and overdose deaths. Some stats:

Source: Esri.

Source: Esri.

Where zoning comes in

Public health organizations are looking to join forces with planners to influence zoning policies for methadone clinics (where drug users' addictions are treated) and needle exchanges (which are intended to curb the transmission of contagious disease). Both types of facilities produce a steady stream of traffic from drug users, something most businesses and home owners do not want to see in their backyard. On the other hand, they save lives.

"There is a huge lack of treatment facilities in most of the U.S.," says Brandon Marshall, an epidemiologist at Brown University and the scientific director of Prevent Overdose RI, a new Rhode Island initiative that tracks overdose data and evaluates government efforts to thwart the epidemic. "But you face a huge amount of stigma when you try to open them, so I'm interested in understanding how planning can help mitigate some of that."

Jeremiah Lindemann says that planning can help in the development of better substance abuse infrastructure. "GIS can have a role in showcasing that, but also in making sure we are doing it in the right areas."

In addition to his work at Esri, Lindemann is now a public interest technology fellow at the D.C. think tank New America, where he launched the Opioid Mapping Initiative in 2017, which consists of getting government agencies set up with effective mapping tools.

As part of the effort, Lindemann convenes a monthly conference call with a dozen local governments using geospatial analysis to better understand the dynamics of opiate abuse in their communities — and to devise more effective interventions.

He's now looking beyond mere data collection to tackle the thorny policy questions that arise at the intersection of land-use planning and substance abuse. Plotting out where to locate drop-off boxes for residents to dispose of unneeded painkillers (thus keeping them out of the hands of drug abusers) is among the low-hanging fruit.

Jane Calabrese, a counselor in the reentry program of the John Brooks Treatment Center, poses near a mobile clinic in Atlantic City, New Jersey, where she administers daily doses of methadone to inmates at the Atlantic County Justice Facility. The inmates are the first in the state to get methadone, a medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction, from a mobile service while behind bars. Photo by Edward Lea/The Press of Atlantic City Via AP.

"I spend a lot of time talking with police chiefs, public health officials, school superintendents, social service providers, and people like me who have been impacted," he adds. "I think planners need to have a seat at that table, too, because of the sort of decisions we're talking about."

Even more contentious than methadone clinics and needle exchanges are supervised injection facilities, which have yet to be established in a single U.S. city. These are places where addicts can use drugs under the supervision of trained staff, with access to clean needles and naloxone in the event of an overdose.

Critics say such places would increase drug use, while others say they could keep users alive so they can enter treatment and recover. Reducing drug use in parks and other public places is another potential benefit.

Before coming to Rhode Island, Marshall was part of a scientific team evaluating Insite, a supervised injection facility in Vancouver — the first and, until recently, only one in Canada — which has been in operation since 2003. He says an overlooked aspect of SIFs is that they create a safe space where drug users feel comfortable interacting with health care providers — and therefore are more likely to enter treatment.

In 2016, Insite served 8,040 people in its injection room, where the staff intervened in about 1,800 overdose interventions and provided 5,321 referrals to various social and health services. The project is widely considered a success — 65 percent of Vancouver residents support it — and several other SIF facilities have recently opened across Canada.

While dozens of SIFs already exist in Europe and other parts of the globe, none have managed to push through community opposition in the U.S. — or likely legal barriers — although a proposed SIF project in Seattle has been earmarked for funds in the 2018 municipal budget, making it likely to become the country's first.

Where to put SIFs and other facilities is still a huge problem, says Marshall. "Epidemiologically they should be where people are using drugs, where the highest burden of overdose is. But you still see a lot of opposition." Overdose hotspots are increasingly known.

But Marshall stresses that the data available that can help communities "understand the relationships between the built environment and overdose risk" is still the tip of the iceberg.

"It is surprising how little research has been done in this area given where we are at with the opioid epidemic," Marshall says.

Mapping the Availability of Naloxone

New America, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, has started creating national maps showing the locations (in red) of pharmacies and clinics providing Naloxone to the public. More than 25,000 locations are already on the map; Walgreens, CVS, Walmart, and several local governments have contributed data.

Naloxone (known commonly by the brand name Narcan) counters the effects of opioid overdoses by rapidly reversing the depression of the central nervous and respiratory systems, allowing overdose victims to resume breathing. It is available without prescription in 41 states. First responders, caregivers, and family members have it on hand in case of an emergency.

Source: Esri

A regional approach

Source: Addiction Treatment Forum.

That's why the Greater Portland Council of Governments, comprised of 26 municipalities in southern Maine, hired substance abuse prevention specialist Liz Blackwell-Moore in 2017 to engage with local government agencies and NGOs in the region. Blackwell-Moore sent a "community scan" to about 50 organizations to better understand how, and where, local residents were becoming vulnerable to substance abuse. She then organized a presentation at the annual gathering on the physiology and psychology of substance use disorder (a term she prefers over addiction), an Opioids 101 of sorts to help people see the problem as a disease.

"Learning about the root causes helps to break down the stigma, and then municipal leaders are more likely to want to invest in prevention, treatment, and recovery," she says. "They begin to understand it as a problem that can be solved, not just a moral failing."

The opioid epidemic is hardly confined to inner cities and other urban areas. It has advanced rapidly in rural America, starting with an increase in prescription opioid-related deaths in 1999. Per capita, the overdose rate is higher in rural counties, and it's increasing more than three times as fast as in urban areas. Zoe Miller, a public health specialist at the Greater Portland Council of Governments, says opioid addiction is particularly difficult to address in rural areas because the holes in the social safety net are larger, and attitudes surrounding drug use are more conservative.

Rural drug users often lack access to professional treatment: Public transportation is scarce, and treatment facilities are often far away. Miller, whose jurisdiction includes a large rural area outside of Portland, sees this as a regional infrastructure problem.

Source: Alcohol and Drug Abuse Treatment Programs.

"We have people here who spend their whole day getting methadone, because the methadone clinic is not close to where they live, and we have a limited public transit system," she says. "One of my initiatives right now is to get public health and social service professionals to become champions for good public transit."

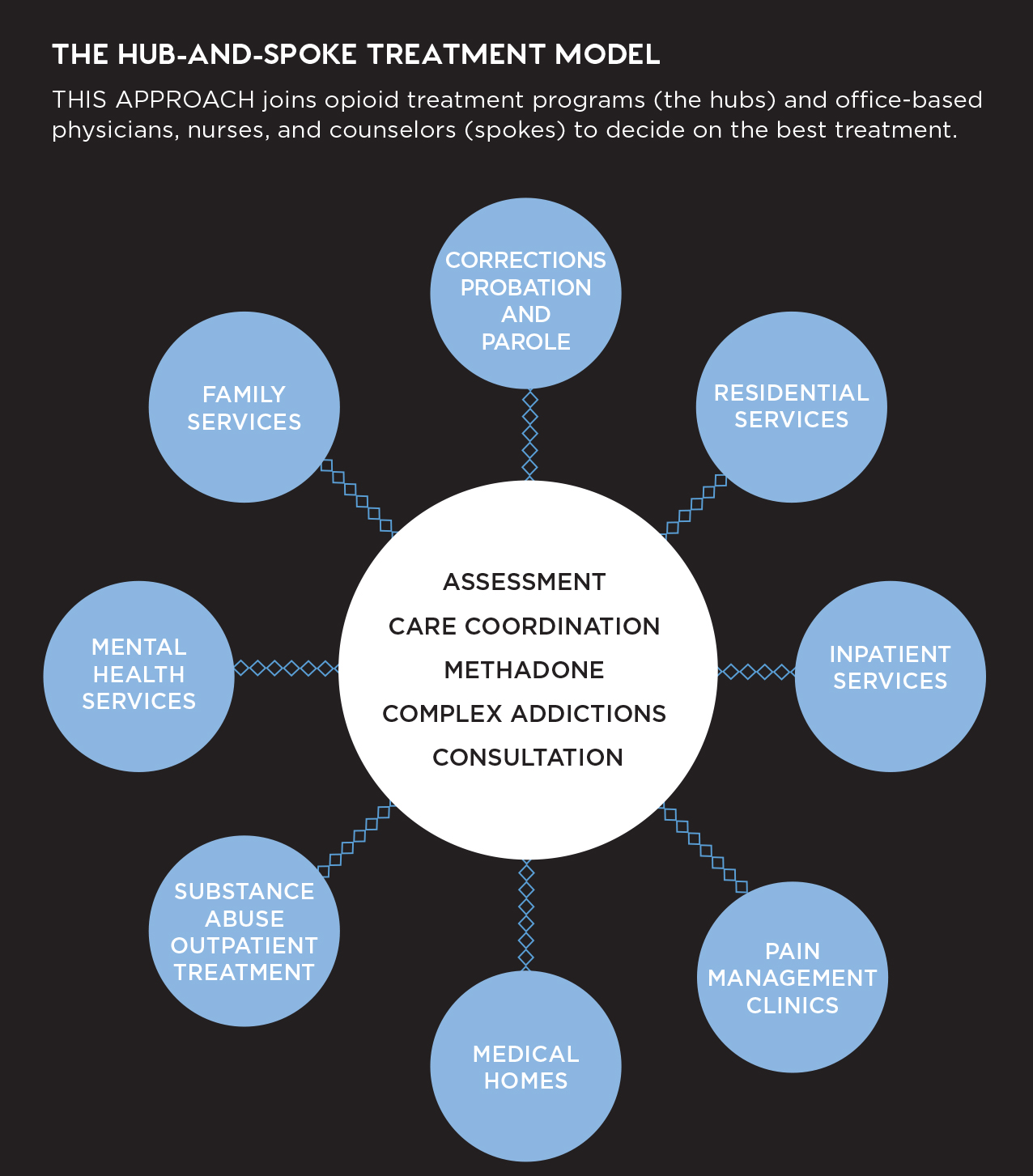

John Gale, a health policy expert studying substance use disorder in rural communities at the University of Southern Maine, recommends the "hub and spokes" model for addressing the crisis: opioid treatment centers located in larger cities and towns (hubs) linked via referral with a network of doctor's offices, counselors, social services organizations, and law enforcement agencies spread throughout smaller communities (spokes). The hubs provide expertise and substance abuse treatment, which is often lacking in rural communities, and coordinate the efforts of the many spokes needed to carry out effective, individual treatment by creating an integrated database to shepherd patients through each aspect of the recovery process.

"Local communities often do not have the specialized hard-core treatment services that [substance abusers] need," says Gale. "So the idea is to develop linkages with bigger health care systems that support local providers through consultations and the provision of certain services that they can't afford."

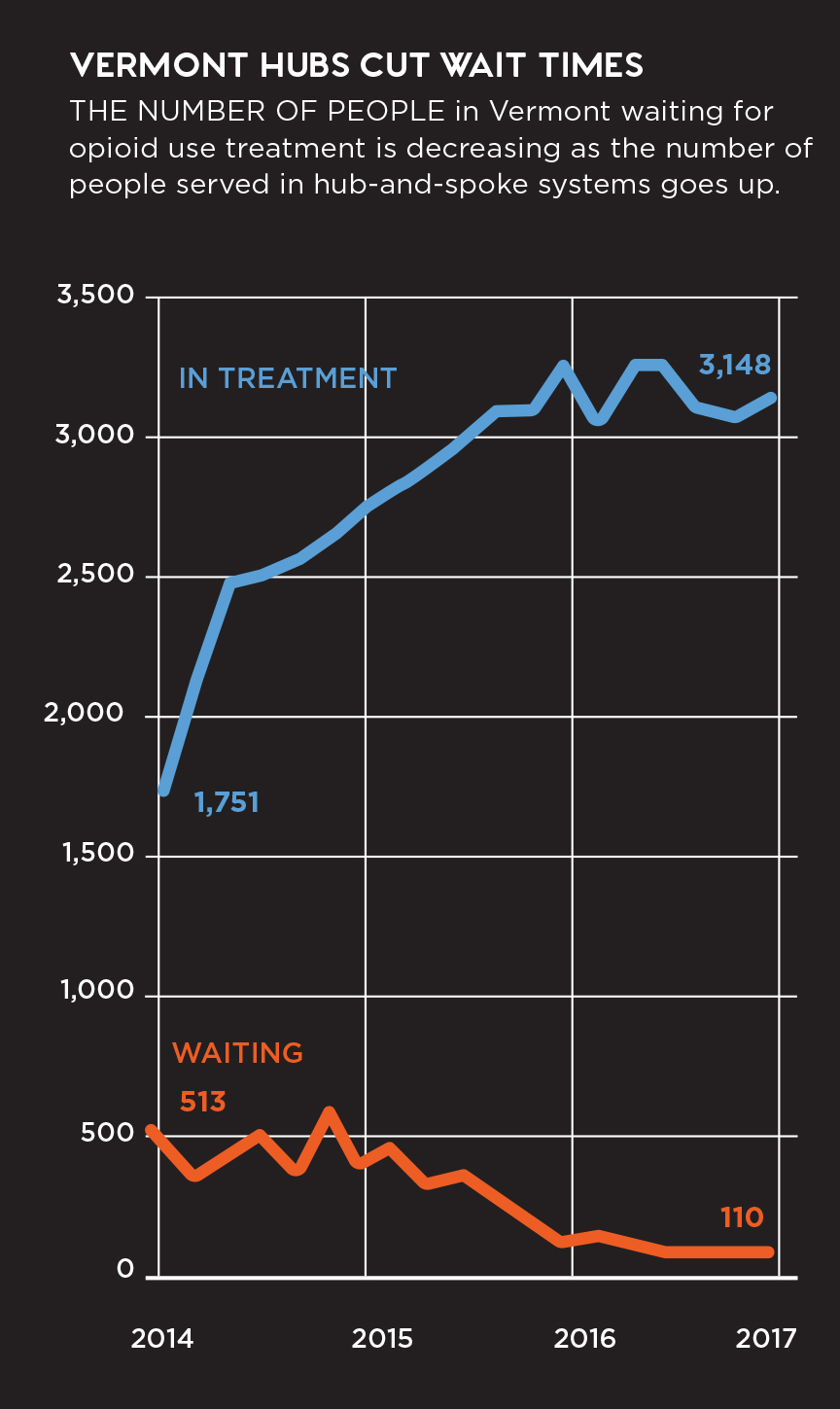

The hub-and-spokes model was pioneered in Vermont under the leadership of former Gov. Peter Shumlin, who in 2014 devoted his entire state of the state address to the opioid epidemic. Vermont established the Care Alliance for Opioid Addiction, which currently counts eight geographically distributed hubs and dozens of spokes in its network. The program is often pointed to as one of the only "success stories," because it has made treatment more accessible to more people: In January 2015, the Vermont Department of Health reported that there were over 600 individuals on the waiting list for treatment services; in April 2016, that number had dropped to 105. Nonetheless, overdose deaths have risen steadily over the last five years, jumping 41 percent in 2016 alone.

Gale also reports that public awareness of the problem — and acceptance of the sort of infrastructure needed to address it — is growing in this highly rural state. But he warns that quick fixes are unlikely, citing studies showing that opioid users typically relapse four to five times during their treatment phase before achieving long-term recovery.

"In rural places where the population and the economy are in decline, we are never going to have enough resources, so the question is how do we begin to work with the community to fix the underlying drivers and develop systems to help people get beyond their substance use problem in a way that conserves those scarce resources?" Gale asks.

"The community really has to be the solution, which means engaging community members in solving the problem — I think that's a role planners can play in this."

Brian Barth is a freelance journalist with a background in urban planning.

Resources

An Esri project offers interactive maps of prescriptions, overdoses, providers, government response, communities taking action, and other aspects of the crisis. http://bit.ly/2agsQoQ