Planning October 2018

People Over Parking

Planners are reevaluating parking requirements for affordable housing.

By Jeffrey Spivak

Like a lot of cities, Minneapolis has experienced the dual trends of rising multifamily rents and dwindling housing affordability. For years it offered the usual carrots of tax incentives and development subsidies for residential projects with affordable units. But three years ago, it tried a different strategy: The city slashed its multifamily parking requirements in certain parts of town.

The usual ratio of one parking space for every one unit was cut in half for larger apartment projects and was eliminated entirely for projects with 50 or fewer units located near high-frequency transit. Lo and behold, the market mostly responded in the exact ways planners had predicted.

Apartment developers proposed projects with fewer parking spaces. That lowered the cost of construction. So, such projects began offering rents below the market's established levels. New studio apartments, which typically went for $1,200 per month, were being offered for less than $1,000 per month.

"There's definitely a new type of residential unit in the market that we haven't seen much before," says Nick Magrino, a Minneapolis planning commissioner who has researched apartment development trends since the parking code change. "Outside of downtown, there's been a lot of infill development with cheaper, more affordable units."

Tinkering with minimum parking requirements is not new. Cities have been fiddling with regulations for decades, sometimes raising them, sometimes lowering them, and sometimes giving variances for specific projects. What's different now is an evolving understanding that urban lifestyles are changing, traditional parking ratios are outdated, and too much supply can be as harmful as too little.

So there's a burgeoning movement of municipalities across the U.S. reducing or eliminating parking requirements for certain locales or certain types of development or even citywide.

"This would have seemed inconceivable just a few years ago," says Donald Shoup, FAICP, a Distinguished Research Professor in UCLA's Department of Urban Planning who has studied and written about parking policies for years and is considered the godfather of the current reform movement.

Over the past three years, a Minnesota-based smart-growth advocacy organization called Strong Towns has compiled, through crowdsourcing, more than 130 examples of communities across the country addressing or discussing parking minimum reforms. And that list hasn't captured all the cities taking actions.

Communities are reforming these regulations in a variety of ways.

Some have ditched parking minimums entirely. Buffalo, New York, in early 2017 became the first U.S. city to completely remove minimum parking requirements citywide, applied to developments of less than 5,000 square feet. Late last year Hartford, Connecticut, went a step further and eliminated parking minimums citywide for all residential developments.

Some have targeted their reforms to certain areas or development districts. Lexington, Kentucky, earlier this year scrapped parking requirements in a shopping center corridor to allow the development of new multifamily housing. Spokane, Washington, this past summer eliminated parking requirements for four-plus-unit housing projects in denser parts of the city.

Some have tied new policies specifically to spur affordable housing. Seattle this past spring eliminated parking requirements for all nonprofit affordable housing developments in the city, among other provisions. A couple of years ago, Portland, Oregon, waived parking requirements for new developments containing affordable housing near transit. Also in 2016, New York eliminated parking requirements for subsidized and senior housing in large swathes of the city well served by the subway.

Even some suburbs are doing it. Santa Monica, California, removed parking requirements entirely last year for new downtown developments as part of a new Downtown Community Plan. And this year, the Washington, D.C., suburban county Prince George's, Maryland, revised its zoning code to significantly reduce parking minimums.

"We're trying to create a new model of mobility and not emphasize the car as much as we've done in the past," says David Martin, Santa Monica's director of planning and community development.

Building Parking Raises Rent

Parking costs a lot to build, and that cost usually ends up raising tenant rents.

$5,000: Cost per surface space

$25,000: Cost per above-ground garage space

$35,000: Cost per below-ground garage space

$142: The typical cost renters pay per month for parking

+17%: Additional cost of a unit's rent attributed to parking

Source: Housing Policy Debate, 2016

Carless in Seattle: Plymouth on First Hill's apartments are now home to some of the city's formerly homeless disabled population. Photo courtesy SMR Architects and Plymouth Housing Group.

Catalysts for change

Three primary factors are driving this new reform:

1. Cities Already Have More Than Enough Parking.

The Research Institute for Housing America, part of the Washington, D.C.-based Mortgage Bankers Association, used satellite imagery and tax records this year to tally parking space totals in different- sized U.S. cities, and determined that outside of New York City, the parking densities per acre far exceeded the population densities.

Meanwhile, two different groups — TransForm, which promotes walkable communities in California, and the Chicago-based Center for Neighborhood Technology, a nonprofit sustainable development advocacy group — have both conducted middle-of-the-night surveys of parking usage at apartment projects on the West Coast and in Chicago, respectively. They consistently found one-quarter to one-third of spaces sat empty. The Chicago center concluded "it is critical to 'right size' parking at a level below current public standards."

2. Transportation Preferences Are Shifting.

A variety of converging trends point to the possibility of fewer cars in the future. Fixed-rail transit lines continue to be developed in more urban centers, and millennials are not driving as much as previous generations. Meanwhile, transportation alternatives are proliferating, from passenger services such as Uber to car-sharing services such as Zipcar. Then there's the potential of driverless cars and the expansion of retail delivery services.

3. Bottom Line: We're Going to Need Much Less Space to Store Cars.

In fact, Green Street Advisors, a commercial real estate advisory firm, analyzed what it calls the "transportation revolution" — encompassing ride-hailing services, driverless cars, etc. — and estimated that U.S. parking needs could decline by 50 percent or more in the next 30 years.

"In the old days, you built an apartment and you expected it needed two cars," says Doug Bibby, president of the National Multifamily Housing Council, an apartment trade association in Washington D.C. "Those parking ratios are outdated and no longer valid in any jurisdiction."

Concerns about housing affordability

With the U.S. economy reasonably strong and most urban crime rates on a long-terms decline, housing costs have increasingly emerged as a hot-button issue. In Boston University's nationwide Menino Survey of Mayors last year, housing costs were cited as the number one reason residents move away, and more affordable housing was the top-ranked improvement mayors most wanted to see.

"It's on the minds of mayors now more than it has been in the past," says Kimble Ratliff , the National Multifamily Housing Council's vice president of government affairs.

They're concerned because there's ample evidence of a continued national shortage of affordable housing. The latest "State of the Nation's Housing" report from Harvard University's Joint Center for Housing Studies noted that a decade-long multifamily construction boom has increased total occupied rental units by 21 percent, but mainly at the top end of the market. Total units deemed "affordable" — costing less than 33 percent of median income — have remained basically static during the last decade, while the number of extremely low-income renter households has grown by more than 10 percent. The 2018 report concluded that there is a "tremendous pent-up demand for affordable rental housing."

So as cities have searched for ways to generate more affordable housing, parking has emerged as an easy target. Parking ratios are simple to change, and the process doesn't lead to future cost obligations like subsidies do.

That was the approach taken by Seattle this year. "The number one issue facing our city is the lack of housing options and affordability. We're looking to remove any barriers to the supply of housing, and parking is one of them," says Samuel Assefa, the director of Seattle's Office of Planning and Community Development.

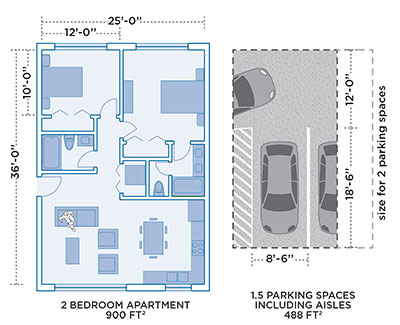

Living Space versus Parking Space

The typical median parking required for a two-bedroom apartment in many large North American cities is more than half the size of the apartment itself.

Source: Seth Goodman, graphicparking.com.

Impacts on housing costs

Planners' shifting strategies toward parking are now supported by a growing body of evidence that parking requirements negatively impact multifamily housing, especially affordable projects.

In a nutshell, building parking costs a lot, and that cost usually ends up raising tenant rents.

Various studies indicate that surface parking lot spaces cost upwards of $5,000 each, while above-ground parking garages average around $25,000 per space and below-ground garages average around $35,000 per space. That can translate into higher rent, particularly in big cities. Two UCLA urban planning professors studied U.S. rental data and reported in the journal Housing Policy Debate in 2016 that garage parking typically costs renter households approximately $142 per month, or an additional 17 percent of a housing unit's rent. Other studies have found even larger impacts on rents.

"That can be a significant burden on lower-income households," says David Garcia, policy director of the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California–Berkeley.

Changing that equation can help produce additional affordable housing. That's a scenario actually playing out in Portland, Oregon.

In 2016 the Portland Community Reinvestment Initiatives, a nonprofit developer and manager of low-income housing, began planning a 35-unit senior housing project called Kafoury Court. At the time, Portland's code required providing five parking spaces for the project, and the developer was struggling to find financing. But late that year, the city changed its parking requirements, and Kafoury now only needs to provide two spaces.

While that change doesn't seem like much, it allowed the development to be totally redesigned. A first-floor parking garage was no longer needed, so the building has been scaled back from five stories to four stories, which led to cost-saving ripple effects. "This has made the project financially feasible," says PCRI's Julia Metz.

She adds: "We prefer to build houses for people, not cars. When it comes down to choosing space for people or parking, we're going to choose people."

Affordable housing projects, with their lower rent revenue streams, are already challenging to finance. So parking is an increasingly key factor in whether or not a project works financially. But to developers, reducing or removing parking requirements does not mean eliminating parking supply. It simply allows developers to decide how many spaces to build based on market and locational demand.

"I've had developers say to me, 'Hey, I could make this deal work if I only had to build a garage that's one-third smaller,'" says Greg Willett, chief economist of RealPage, a provider of property management software and services. "Any way you can take costs out of the deal is meaningful."

Carless in Seattle: The mixed use transit-oriented development Artspace Mt. Baker Lofts is located on the Central Link light-rail line. It has bicycle storage and a reserved car-share space, but no parking garage. Photo courtesy SMR Architects and Artspace.

'The debate is now won'

When it comes to utilizing parking to augment planning and development policies, U.S. cities still have a long way to go to catch up to some European counterparts. Zurich, Switzerland; Copenhagen, Denmark; and Hamburg, Germany, have all capped the total number of allowable parking spaces in their cities. Oslo, Norway — where a majority of center-city residents don't own cars — is pursuing plans to remove all parking spaces from that district, to be replaced by installations such as pocket parks and phone-charging street furniture.

And last year the largest city in North America, Mexico City, eliminated parking requirements for new developments citywide and instead imposed limits on the number of new spaces allowed, depending on the type and size of building.

In the U.S., however, parking is still sacred in many places. Sometimes when parking reductions are proposed for a certain urban district or a specific new development, nearby residents complain it will force new renters to park on their residential streets. Because so many people still own cars, the National Multifamily Housing Council's 2017 Kingsley Renter Preferences Report ranked parking as renters' second-most desired community amenity, behind only cell-phone reception.

Not surprisingly, then, some places are still demanding more parking, not less. In Boston, for instance, an influx of new residents clamoring for parking in the booming South Boston neighborhood led to zoning code changes in 2016 that require developers to build two-thirds more off-street parking than before.

Nevertheless, the movement to reduce parking is now widespread, involving big cities and small towns, urban districts and suburban locales, affordable housing and market-rate units. "It's pretty well accepted now that reforming parking minimums is a good way to manage cities," says Tony Jordan, founder of Portlanders for Parking Reform, which has advocated for better parking policies. "The debate is now won."

The lessons for planners are, first, to be open to adjusting parking policies in zoning codes and comprehensive plans and, second, to be flexible in crafting new parking limits depending on the location or desired outcome, such as spurring affordable housing development.

"As we update our policies, we as planners need to learn from the past and adjust," says Seattle planning director Assefa. "We constantly need to tweak our policies and face the challenges of what's not necessarily working. More often than not, there's significant space dedicated to the car that is not utilized."

Jeffrey Spivak, a market research director in suburban Kansas City, Missouri, is an award-winning writer specializing in real estate planning, development, and demographic trends.