Planning October 2018

When Every Day Is Sensory Overload

Learning to plan with people with autism, not for them.

By Kyle Ezell, AICP CUD; Rick Stein, AICP; and Gala Korniyenko

Planner Rick Stein, AICP, has a teenage son, Justin, who has autism. Sometimes it's challenging for Justin to get the most out of his community, particularly when it comes to getting around. Take biking. Justin likes to ride, but finds it hard to do so in his Westerville, Ohio, neighborhood near Columbus. "Neurotypical" cyclists have a certain built-in tolerance for conflict with automobiles and pedestrians, and they are able to manage a minimum amount without difficulty. Justin's tolerance, however, is very low — so low that he sometimes chooses to ride in the grass rather than the street or sidewalk. "It is very frustrating for him," Stein says.

A seemingly standard street scene on High Street in Columbus, Ohio, creates challenges for people with autism: light and noise, safety, public transit, street crossings, and crowded spaces. Photo by RSBPhoto/Alamy Stock Photo.

Riding the bus can also be difficult. If it doesn't arrive on time or if two buses arrive simultaneously, Justin experiences anxiety and confusion. "This often results in poor decision making for the moments immediately thereafter," Stein adds. Everyday wayfinding can be challenging, too, especially when streets are not oriented north-south and east-west. The same is true when Justin gets dropped off at a shopping center, school, or other busy places and has to make his way through a large parking lot to his destination.

Then there is street noise and other sensory inputs that can interfere with Justin's ability to make good choices. "Too many stimuli compete for processing space in his brain. He often will wear earplugs to reduce the noise, but that can be dangerous when navigating in a city," Stein says.

Stein — along with a group of planners, researchers, planning students, and community stakeholders — thinks that it doesn't need to be so hard for people with autism to fully enjoy and engage with their communities.

The first step, they say, is thoughtfully including them in planning processes, so that planners and others can understand their ideas and concerns. Knowing how to design and facilitate more inclusive public meetings to accommodate people with autism allows the voices of this significantly overlooked and underserved population to be heard.

Here's a look at key lessons learned about public participation and autism from planning practice research undertaken at Ohio State University.

What Is Autism?

Autism, often referred to as Autism Spectrum Disorder or ASD, denotes a wide range of functional, cognitive, social, and behavioral impacts associated with this disability. One in 59 people born in the U.S. fall somewhere on the autism spectrum, a figure equivalent to 5.52 million Americans, and this number continues to grow.

Symptoms present differently in every person, but generally, people with autism have difficulty communicating effectively, are challenged by sensory overload, engage in repetitive behaviors, often struggle with fine motor skills, and generally process information differently than the neurotypical population. Symptoms of autism, as should be true of symptoms of any medical or physical disability, must not impede their voices in the planning process.

A gap in the research

As a concerned father, Stein came to Ohio State's City and Regional Planning Program with a question that was also very personal: How can planners create places where people with autism can thrive?

Stein, a professional planner, owner of Urban Decision Group, and trustee of Autism Living, a Columbus nonprofit corporation concerned with housing for adults with autism, teamed up with his fellow coauthors on this article, Kyle Ezell, AICP cud, an Ohio State professor of practice, and Gala Korniyenko, an Ohio State PhD planning student and Ezell's teaching assistant. Korniyenko researches planning and disabilities, including the relationship of mental health to the accessibility of physical spaces. None of the authors are themselves on the autism spectrum.

"Scholars recognize gaps in planning research associated with Autism Spectrum Disorder and planning practitioners recognize community members who may be left out of the planning process," Korniyenko says. "Since autism involves a spectrum of symptoms, the academy and planners can work together to design and implement participation methods that include as many people as possible."

Ezell took Stein's question into the classroom, where over the past two years he led three courses and a team of 33 graduate and undergraduate planning students in the design of focus groups and a design charrette dedicated to planning for and with people with autism. Ezell added 37 professionals to the charrette team, including planners, public health officials, Americans with Disabilities Act compliance officials, disability professionals and activists, architects, landscape architects, civil engineers, neuroscientists, and others in affiliate fields.

Charrette participants with autism may prefer to use paper and markers to flesh out their ideas. Photo by Philip Arnold.

To discover how planners can create places where people with autism can thrive, the team needed input from people uniquely qualified to answer the question — people with autism.

But they could not merely invite people with autism to a typical participation meeting and expect success. Those events can be loud, distracting, and full of overlapping conversations and too many ideas to comprehend at once.

So the team designed a participation method that helps to bridge the existing knowledge about the needs of adults with autism and the practice of city planning.

Resources included advice from valuable guest lecturers, as well as a semester-long literary review on understanding autism and its symptoms. Emilio Amigo, PhD, a prominent Columbus licensed counselor and psychologist who focuses on the health and well-being of people with autism, was another important part of filling that knowledge gap. Amigo's clients with autism regularly discussed lifestyle and built environment issues in their sessions, and a great deal of what the team learned about public participation was developed from his decades of experience. Nineteen of Amigo's clients formed the first focus group, supported by students.

As it developed a participation model for people with autism, the Ohio State team broke down the public meeting into three aspects: preparing for the meeting, conducting it, and what to do afterward.

A charrette participant presents ideas on desired residential possibilities for high-functioning people with autism using a formal presentation style. Photo by Philip Arnold.

Premeeting Prep

Preparation before meeting is important for successful engagement opportunities with people with autism. Doing so provides a better chance that their opinions will be expressed and properly recorded. Here are some key tips.

LEARN ABOUT AUTISM

Planners should first familiarize themselves with what autism is and how to be sensitive to the needs of people with autism. In a similar way that Amigo advised the Ohio State team during the participation process, planners can join with local licensed mental health professionals who want to serve their community.

CHOOSE THE RIGHT VENUE

Choosing an appropriate facility may be the most important step in accommodating people with autism, especially selecting the meeting room. For a charrette with adults with autism, the team assessed how meeting spaces affect human senses. For instance, the research suggested that flickering lights, unusual colors, and overly bright lights should be avoided. Since the participants with autism would be discussing important transportation, housing, and recreation issues, a comfortable space encourages meaningful conversations.

The team carefully inventoried room sounds such as any noises coming from the lights or random dim noises throughout a room, and noticed any sounds from heating or cooling systems or echoes from inside or outside in halls. It was important to eliminate scents, especially those from cleaning solutions and perfumes or colognes. Room colors were evaluated for neutral colors void of unusual textures that might distract. The team consulted with Dr. Amigo in the final decision of a meeting space for the event: a quiet, comfortable, and accessible section of the OSU City and Regional Planning laboratory.

FAMILIARIZE PARTICIPANTS WITH THE SPACE

Many people on the autism spectrum find comfort understanding where they are going and what will be there. With the meeting space selected, detailed floor plans — including directions, labels for bathrooms and exits, interior landmarks, quiet spaces, and any other important spots — should always be made available online before the event. For future events, floor plans should clearly point out areas where potential disruption or overstimulation cannot be mitigated, either along the journey to or from the meeting space or in the room itself.

ESTABLISH QUIET/REFRESH ROOMS

Four quiet rooms near the main meeting space were available for participants to recharge. Signs and wayfinding directed users to those rooms from the main meeting space, and meeting facilitators encouraged their use. In the future, the team suggested adding printed meeting materials, including overviews, goals, agendas, and media for offering ideas for users to remain engaged if they wish.

At the meeting

During the meeting, the following suggestions can boost communication and comfort during meetings.

KEEP VISUALS READY

The team offered simple photos as specific planning issues were discussed. Prompting participants with visuals is important to focusing conversations. As is the case in all public involvement meetings, avoid planning jargon.

ENCOURAGE A SPECTRUM OF SHARING METHODS

No two people are the same, so attendees should be allowed to share their ideas with planners any way they choose. Some might want to formally share in a presentation style. Others may choose to express their ideas by drawing them or having one-on-one conversations with a facilitator who's taking notes. Participants should also be encouraged to employ the gamut of personal technology possibilities.

Another charrette participant uses his personal tablet in the participation process. Photo by Philip Arnold.

Postmeeting alternatives

Following the meeting, it became clear that some participants were not able to participate as much as they would have liked, or may have come up with new ideas after the session's information had percolated for a while. That is why this participation model emphasizes engagement after a meeting on a participant's own terms. One way to do this was to encourage people to connect by sending emails to the facilitators.

Another option can be take-home meetings. In Athens, Ohio, 80 miles southeast of Columbus, city planner Paul Logue, AICP, administers meeting kits, available online or in hard-copy packets, where participants can fill out comments and ideas and send them to city hall. These take-home meetings are offered concurrently with Athens' traditional public workshops, charrettes, and presentations.

"Some people with disabilities, including autism, cannot attend meetings or may not feel comfortable in such environments, but want to contribute to the conversation and provide feedback," Logue says. "They may feel more comfortable in familiar spaces with people they know and trust."

Logue says he also works with the city's disabilities commission "to make sure that their key policies and principles are incorporated into our process."

"People with autism deserve to be considered as equal participants in the planning process and their desires should be represented as strongly and clearly as all others," says Joanne Shelly, AICP, an urban designer for nearby Dublin, Ohio, and a participant in the Ohio State work on planning and autism. "Our staff recognizes that Dublin's street and pedestrian infrastructure, mixed use developments, and mobility options require the voices of our residents with autism. We are embracing a welcome shift toward inclusive participation for people with mental disabilities."

Stein's advice to planners is to plan with people with autism and not for them, so Justin and others can live the best lives they can.

"As his dad and as a planner, I believe that if my colleagues develop a deeper understanding for what people with mental illnesses go through every day it would greatly benefit my family, many others like ours, and the greater community," Stein says.

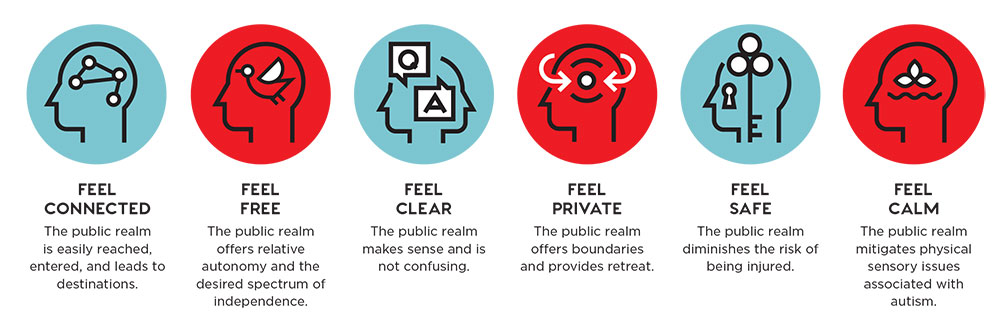

The Six Feelings Framework

The July/August PAS Memo, "Autism Planning and Design Guidelines 1.0" conceptualizes a framework and guidelines that help adults with autism feel included in their communities in a built environment where they can thrive.

When an adult with autism is using public spaces or infrastructure, planning and design implementations should make him or her:

FEEL CONNECTED

The public realm is easily reached, entered, and leads to destinations.

FEEL FREE

The public realm offers relative autonomy and the desired spectrum of independence.

FEEL CLEAR

The public realm makes sense and is not confusing.

FEEL PRIVATE

The public realm offers boundaries and provides retreat.

FEEL SAFE

The public realm diminishes the risk of being injured.

FEEL CALM

The public realm mitigates physical sensory issues associated with autism.

Kyle Ezell is a professor of practice at The Ohio State University's Knowlton School's City and Regional Planning program, and owner of Ezell Planning and Design. Rick Stein is the owner of Urban Decision Group, a Columbus, Ohio, planning firm, and a trustee of Autism Living, a Columbus nonprofit whose mission is to create intergenerational neighborhoods of mutual support for adults with autism. Gala Korniyenko is a PhD student in city and regional planning at The Ohio State University and a member of World ENABLED, an educational nonprofit organization that promotes the rights and dignities of persons with disabilities.