Planning April 2019

From Seed to Sale

As more states legalize marijuana, local planners tackle land-use and zoning challenges to make the new industry work for their community.

By Juell Stewart

Against the backdrop of an eventful national election, 2016 was a pivotal year at the polls for California: 57 percent of state voters approved the Adult Use of Marijuana Act (Proposition 64), a statewide ballot initiative that legalized the possession, sale, cultivation, and use of recreational marijuana and required the state to create a regulatory structure to encompass all commercial aspects, including licensing and taxation.

While nine states plus Washington, D.C., have legalized recreational marijuana use in recent years, in many ways, California is an outlier. While other states are developing regulatory approaches to create entirely new marijuana economies, the Golden State has long had a reputation for having a permissive and progressive marijuana culture. In 1996, it became the first state to legalize medical marijuana for qualified patients via the Compassionate Use Act (sometimes referred to as Proposition 215).

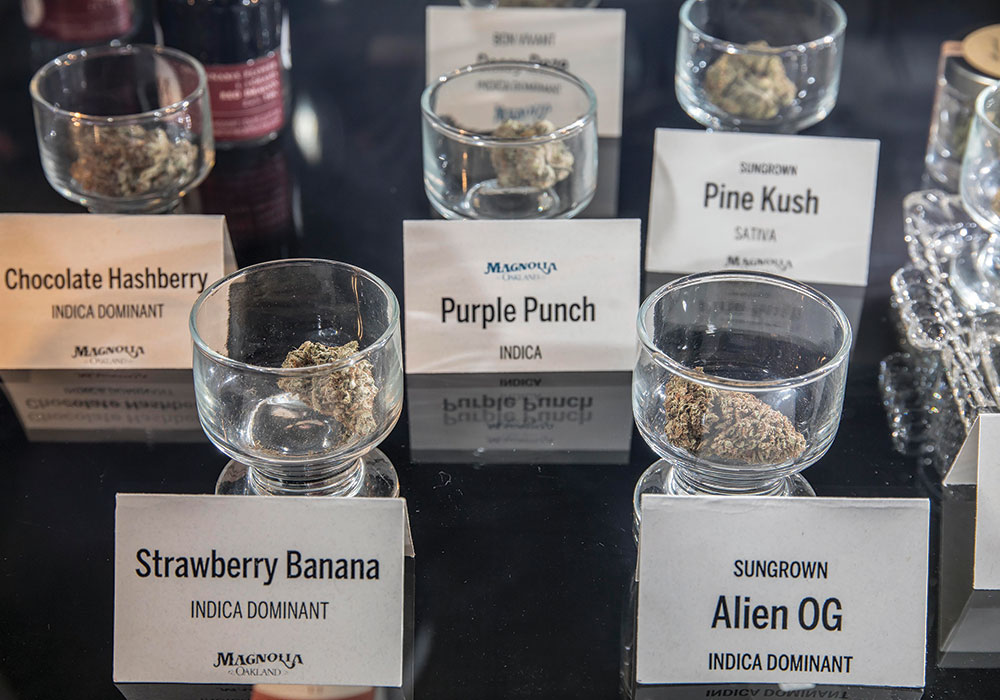

A display at Magnolia Oakland dispensary in California. Photo by Mark Petersen/Redux.

As a result, California already had a thriving infrastructure of cannabis cultivators, manufacturers, and retailers by the time Prop 64 passed. But because there were no official regulatory or licensing structures in place, these businesses existed on the legal periphery, or what some refer to as the "gray market" — not quite in the underground market, since their business activities were enabled by the state, but also not squarely within the realm of legal compliance.

Prop 64, which officially went into effect last January, was the first time that regulators across the state were called upon to develop strategies to formalize the relationship between government and the marijuana industry, from seed to sale. The measure has allowed state regulators to create a broad regulatory infrastructure for licensing while providing local jurisdictions quite a bit of latitude in determining specific planning and zoning approaches according to their communities' needs and priorities.

Exotic strains are a new trend in the cannabis industry. Photo by iStock/Getty Images Plus.

A year in, many counties and municipalities are still working out the details. Where states like Colorado have realized the potential revenue opportunity by collecting business and sales taxes, in California, where land values are already at a premium, local planners have a unique challenge to contain disruptive economic effects as much as possible.

Some California counties and communities see Prop 64 as an opportunity to introduce new economic activity. Others have taken a more restrictive approach, handling land use and zoning for cannabis similarly to the regulations already in place for liquor stores and other locally undesirable land uses. However, the precedent of cannabis being treated like medicine prompted officials statewide to consider the nuances of public and industry opinion.

State and local regulators are still learning and revising their regulations to acknowledge the complicated nature of balancing so many priorities. The lessons learned and wide range of approaches taken so far offer a different perspective — and valuable insights — for planners and policy makers looking to regulate recreational cannabis in their own jurisdictions.

Blunts & Moore was the first dispensary to open under Oakland, California's cannabis equity program. To qualify, individuals must have had a cannabis conviction or live in a community found to be overpoliced with regards to cannabis arrests. The goal of the program is to help them overcome the challenges of marginalized business owners. Photo courtesy Blunts & Moore.

Licensing and regulations

In January 2018, California introduced a two-tiered licensing structure that requires businesses to secure local business permits before they can receive a state cannabis business license. On the state's end, the licensing process is complicated, with the Bureau of Cannabis Control regulating commercial licenses for retailers, distributors, laboratories, and events; the California Department of Food and Agriculture issuing licenses for cultivators; and the California Department of Public Health handling the manufacturing of edibles. This dual system has required local agencies to create their own processes and mechanisms for permitting businesses if commercial cannabis activities are allowed locally.

Some counties have developed entire cannabis departments to handle the regulatory burden; others have relied on the existing conditional use permitting process as a means for signaling local approval to state regulators.

Many jurisdictions that already had substantial cannabis business activity under Prop 215 rules have formed advisory committees to instruct local leaders on how to move forward. "We had dozens of growers that were allowed under the medical market, but we didn't have a regulatory structure to permit them," says Tim Ricard, the cannabis program manager at Sonoma County's Economic Development Board. "We had to think both about how to transition those folks into the legal, regulated market and also how, as this industry grew and matured, it would fit into the traditional agriculture."

Some farmers in Sonoma County were apprehensive about cannabis cultivation on land adjacent to theirs because of the common perception that it would bring illegal activity. There was also concern that cannabis cultivation would quickly turn into a speculative market, driving up land values and making the area prohibitively expensive for existing farmers.

Ricard notes that reassuring community members over concerns about displacement of existing economic activities — even in areas like Sonoma County that have traditionally accommodated cannabis cultivation — is a big challenge for planners.

That makes outreach and education key. The county held an eight-part "Dirt to Dispensary" workshop series to introduce both existing and prospective operators to all aspects of the county's cannabis program — including zoning, permitting, inspections, communicating with neighbors constructively, standards, and business requirements. The program attracted more than 300 participants.

"By bringing [existing cannabis business operators] into the legal market, we're bringing them into the permitting structure that is available to wineries and everyone else," notes Amy Lyle, supervising planner in Sonoma County's Planning Division. The county also implemented a penalty relief program at the outset to allow existing cannabis businesses to continue operations while they pursued their business permit.

A Cannabis History

| 1600–1890s | The U.S. government encourages domestic production of hemp to make rope, sails, and clothing. In the late 19th century, cannabis becomes a popular ingredient in over-the-counter medicinal products. |

| 1906 | Federal Pure Food and Drug Act requires cannabis labeling in over-the-counter remedies. |

| 1900 1920s | Mexican immigrants flood into the U.S. after the Mexican Revolution of 1910 and introduce recreational use to American culture. Now frequently called by the Spanish word marijuana, it is connected to fear and prejudice about the Spanish-speaking newcomers. |

| 1930 | The Federal Bureau of Narcotics is created. |

| 1931 | The list of states outlawing cannabis rises to 29 as fear and resentment of Mexican immigrants increases. |

| 1932 | The Federal Bureau of Narcotics wages the infamous "Reefer Madness" propaganda campaign and encourages state governments to adopt the Uniform State Narcotic Act. |

| 1937 | Congress passes the Marijuana Tax Act, which effectively criminalizes cannabis by restricting possession of the drug to individuals who pay an excise tax for certain authorized medical and industrial uses. |

| 1952, 1956 | The federal government establishes mandatory minimum sentences for marijuana possession and use. |

| 1970 | Congress repeals most mandatory minimum sentences for possession of small amounts of marijuana and categorizes it separately from other more harmful drugs. |

| 1971 | President Richard M. Nixon officially declares the War on Drugs and introduces an era of new mandatory sentencing minimums for possession and distribution of marijuana. |

| 1973 | The Drug Enforcement Administration is created. |

| 1989 | Congress creates the Office of National Drug Control Policy. |

| 1996 | California passes the Compassionate Use Act of 1996, legalizing medical marijuana. |

| 2012 | Washington and Colorado permit retail sales of cannabis. |

| 2014 | Alaska, Oregon, and Washington D.C., legalize recreational use through ballot measure. |

| 2016 | California, Nevada, Maine, and Massachusetts approve ballot measures to legalize recreational cannabis. |

| 2018 | Vermont becomes the first state to legalize recreational cannabis by way of state legislature, and Michigan approves a ballot measure legalizing recreational use. |

Sources: PBS.org, Online Paralegal Degree Center

Building regulatory capacity

Developing a regulatory structure to handle permitting is an important and necessary first step in building a local cannabis economy. The approach a community chooses will often depend on the size of its jurisdiction and the activities that are likely to take place within it.

Many municipalities are finding that housing all cannabis-related functions in a single office that acts as an intermediary with other local departments is an efficient way to go: It helps streamline permitting, outreach, and community relations, and builds cooperation and buy-in among diverse stakeholders.

In July 2015, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors formed a Cannabis State Legalization Task Force to inform the scope and role of what would eventually become the San Francisco Office of Cannabis. That office is responsible for issuing permits and acting as a liaison for business owners, community members, and local agencies.

Centralized offices that coordinate the efforts of multiple city departments are also useful in terms of outreach and education to community members, which is necessary when introducing something like cannabis into a new context, including destigmatization efforts in the wake of the decades-long War on Drugs. Giving the general public a clear point of contact in case of any issues, as well as providing them with the proper resources and information about business developments, can help assuage confusion.

Communities introducing new cannabis regulations can also benefit from working closely with cannabis businesses, both existing and new, to navigate challenges and ensure mutually beneficial outcomes. For example, in its original iteration of state regulations, California's Bureau of Cannabis Control prohibited cannabis manufacturers from sharing kitchen facilities. However, as a result of ongoing outreach and relationship-building with local cannabis operators, the city of Oakland found that rule to be problematic.

"As a practical matter, the cost of building a new kitchen facility was prohibitive to cannabis business owners. We saw an opportunity to help businesses reduce costs by going to Sacramento and advocating to the BCC to create a shared kitchen model because of the need we observed on the ground," says Greg Minor, assistant to Oakland's city administrator, who deals specifically with cannabis, special permits and nuisance abatement.

Because of the close relationships Minor has cultivated with local cannabis businesses, he's been able to effectively advocate on behalf of operators, and the BCC has updated its regulations to allow for shared-use commercial kitchen facilities in jurisdictions across the state.

Economic development opportunities

Hollywood director and winemaker Francis Ford Coppola has invested in a new venture that markets luxury marijuana products along with his signature wine brand. Photo by Justin Hargraves.

Besides lowering administrative and enforcement expenditures, the potential for economic stimulation is an attractive reason behind legalization. Local governments can collect sales tax and business licensing fees. Local economies can also benefit from a range of ancillary economic activity, from tourism to commercial corridor revitalization. Pete Parkinson, AICP, former planning director in Sonoma County, pointed out that cannabis legalization has even been a boon to the region's existing wine industry.

"There's a close connection between wine industry tourism and a burgeoning connection between craft brewing and tourism, so I would guess there will be synergies without a doubt," Parkinson notes.

In fact, the popular Francis Ford Coppola winery headquartered in Geyserville, California, recently introduced an independent operation that markets luxury marijuana products in conjunction with the signature Francis Ford Coppola wine brand.

The Sonoma County Fairgrounds also hosts the annual Emerald Cup — a showcase and competition between local cannabis producers considered to be the "Academy Awards of Cannabis." The event consistently draws tens of thousands of people to Santa Rosa, along with economic activity.

The opening of the recreational market has brought some in real estate changes in the area too. Although the Sonoma County Economic Development Board is still collecting data on the specific effects of the cannabis industry, Cannabis Program Manager Tim Ricard says that it has driven vacancy rates in commercial and industrial zones down, while price per square foot has risen since legalization in Santa Rosa, Sonoma's county seat.

Oakland's Green Zones for Cannabis

Oakland allows and licenses all major types of medical and adult-use cannabis businesses, but steers most cannabis activities to designated areas. This "Green Zone" map dovetails with its existing zoning code, with restrictions for each area as noted below. Right now most of the cannabis businesses are located in industrial zones.

Source: ESRI

Zoning and land-use considerations

The biggest tools planners have wielded in regulating cannabis activities are buffering, zoning overlays, and permitting. California state law delegates land-use and zoning authority to cities and towns, leading to quite a varied landscape statewide in terms of location and type of business activity.

In many cities, a buffer zone of 1,000 feet from sensitive uses like schools, parks, and day care centers is required; in San Francisco, the most densely populated city in the state, that buffer was reduced to 600 feet to compensate for the relatively small size of the city. Generally, commercial manufacturing and cultivation are prohibited in residential areas.

"Green Zones" have also been established in some municipalities to steer cannabis activities to designated areas. This typically allows businesses to be established by right, without being subject to a lengthy zoning review process. This strategy has the bonus of stimulating growth in previously blighted industrial areas and can strategically introduce new activity in areas that need new life. That was the case in Oakland, where the city aligned cannabis business uses with its existing zoning code; currently the majority of cannabis activity is located in industrial zones, since they are typically not open to the public.

Oakland has also used municipal code and permitting processes to incorporate its equity priorities directly into cannabis regulation. It was the first city in the country to launch a cannabis equity program, designed specifically to acknowledge the barriers that black and brown business owners face in the wake of the War on Drugs, in hopes of repairing some of the harm that overpolicing has done within these communities.

As a result of a race and equity analysis of medical cannabis regulations conducted by Oakland City Council shortly after Prop 64 passed, the city set an ambitious goal of requiring that half of all cannabis business permits issued in the initial permitting phase must go to equity applicants. To qualify, individuals must have either had a cannabis conviction or lived in a community that has been found to be overpoliced with regards to cannabis arrests, and they must make no more than 80 percent of Oakland's area median income.

The Oakland model also looks to overcome the challenges marginalized business owners might face in securing operations space. It introduced a mentorship component by pairing each equity applicant with an incubator business, which agrees to provide equity applicants with free space to operate on their premises in exchange for receiving incentives and expedited permitting.

Since Oakland launched its program, San Francisco and Los Angeles have both followed suit, iterating on the eligibility criteria and incentives. Oakland's Greg Minor emphasizes the importance of centering equity in local cannabis discussions: "The sooner a jurisdiction has these conversations and tries to address these systemic issues, the sooner they'll be on the path toward resolving them, as opposed to tackling them later down the line."

Juell Stewart is an urban planner and policy researcher based in San Francisco.

Planning and Policy Lessons from Colorado

Before and after in Aurora, Colorado: New cannabis businesses have spurred rehab projects in vacant commercial properties, such as this former Taco Bell. Photos Courtesy Aurora Marijuana Enforcement Division.

Mitigate Nuisances

Implementing standards for mitigating nuisances can be an opportunity to set industry best practices.

Kim Kreimeyer, a planner with Aurora, Colorado's Marijuana Enforcement Division, says that Aurora wanted to distinguish its cultivation facilities from surrounding cities, which had a reputation for having a noticeable and distinct marijuana smell outside of the industrial buildings. The result is what Kreimeyer describes as the most stringent odor control standards in the entire state. But they left the "how" up to the individual businesses.

"We did not prescribe how the industry was to mitigate odor. We left it up to them," Kreimeyer says of the regulation and incentive-driven effort.

"Initially we saw licensees use carbon filters, while some transitioned to ozone filtration, while others utilize both," she says.

In an industry with rapidly evolving technology, this kind of approach encourages businesses to innovate to satisfy local requirements.

Regulate Lighting and Energy Usage

Similarly, Aurora's indoor-only cultivation offers an opportunity to affect energy reduction benchmarks by introducing rigid guidelines for lighting. Grow operations in the city are required to have extra cooling mechanisms, and most of the growers have transitioned from fluorescent lighting to more energy-efficient LED lights, keeping costs and usage low.

Encourage Revitalization

Aurora's cannabis cultivators were also limited in the spaces they could access shortly after recreational legalization.

Because many new developments and shopping centers were still bound by bank-backed mortgages, property owners were hesitant to jeopardize their investments by running afoul of federal law.

This shutout from leases in new construction meant cannabis businesses had no choice but to occupy vacant properties, which spurred adaptive reuse across the city.

"In the economic downturn, we had vacant buildings that operators were able to lease. From a land-use perspective, we required that the site plan was up to date, so we got replaced dead or dying landscaping, renovated parking lots, etc," she says.

Kreimeyer says this was a catalyst behind many rehabilitation projects in commercial and industrial buildings.

Be Flexible

Kreimeyer's advice to planners grappling with regulating cannabis — whether they are in communities introducing an entirely new industry or in towns balancing a new regulatory framework for a legacy business sector — is simple: "Be flexible. It's going to be changing constantly. It will be a learning process, and things will come up continuously that will need to be addressed."

Planners and policy makers can work together with constituents and business owners to determine the appropriate approach that fits their community's needs.

In a rapidly changing industry, government officials have to be willing to learn and share best practices.

Can Cannabis Policies Catch Up?

A man dressed as a marijuana leaf walks among attendees at the cannabis-themed Kushstock Festival at Adelanto, California, in 2018. Photo by Richard Vogel/AP.

Financing

By far, the biggest hurdle for cannabis operators is access to capital. Financial institutions are regulated by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which guarantees a bank's deposits. However, doing business with a cannabis operator puts this insurance at risk since it runs afoul of federal regulations.

The effect is essentially a de facto ban on banks doing business with the cannabis industry. Since they're cut off from more mainstream methods of fundraising and financing, a significant number of businesses rely on cash and private investors.

This reliance on cash financing means that business owners from marginalized communities are all but excluded from entering the marketplace, even in cities like San Francisco and Oakland that have provisions to prioritize eligible applicants that meet certain income and residency criteria in equity programs.

Cash transactions also pose a security risk; for neighbors near dispensaries that handle tens of thousands of dollars of cash daily, this can be a serious point of contention.

California State Treasurer John Chiang convened a Cannabis Banking Working Group to explore the feasibility of introducing a statewide public bank that would allow cannabis businesses to circumvent the conventional banking industry and to alleviate the state-federal conflict. Ultimately, it was deemed too much of a legal and financial risk for the state to take on, and Chiang urged federal regulators to remove cannabis from the list of scheduled drugs to resolve the issue once and for all.

Event Permits

In September 2018, California Governor Jerry Brown signed Assembly Bill 2020, which allows local jurisdictions to approve temporary cannabis events, reversing previous Bureau of Cannabis Control rules that restricted events with cannabis consumption and sales to county fairgrounds. In cities like San Francisco — which is home to an annual "unofficial" (and thus unregulated) 4/20 event that attracts more than 10,000 visitors each year — this presents an opportunity to introduce a clear process for event producers that aligns the need for safe consumption sites with the needs of other city agencies.

Obtaining a state Cannabis Event Organizer license requires approval from a local jurisdiction for on-site consumption and sales, so the Office of Cannabis needed to develop a clear process.

In January, the San Francisco Office of Cannabis and the San Francisco Entertainment Commission hosted a panel to introduce the next steps for developing a regulatory structure for event permitting, which drew community interest from local cultivators to coordinators of neighborhood events.

Office of Cannabis Director Nicole Elliott, along with Supervisor Rafael Mandelman — whose district includes popular destinations the Castro and the Mission — developed an intentionally broad framework that gives the Office of Cannabis latitude in issuing permits while also recognizing the need for other agencies to have control over their jurisdictions; for instance, the Recreation and Park Department and the Port of San Francisco both have the power to decline cannabis events on their respective land.

The Office of Cannabis plays the role of an intermediary between the BCC's state-level process and the local interests of the city and county, while maintaining a balance between the authority of existing local agencies. The panel was an example of city agencies working together to include the public on important decisions regarding this new regulatory structure.

Even in a city like San Francisco, which has political will and a history of cannabis events, creating new regulation can be a lengthy process. Community and industry input goes a long way.

Public Consumption

Outside of the context of one-time special events, public consumption remains a complex hot-button issue.

People who live in federally subsidized housing are still bound by the rules of the federal government and face eviction if they consume marijuana, even when it's legal in their jurisdiction.

People who live in multiunit rental housing are also subject to restrictions on their method of consumption.

Aurora planner Kim Kreimeyer believes that public consumption is a key issue that's yet to be resolved on the state level in Colorado; currently, allowing on-site consumption is up to the municipality's discretion in California.

Offering people safe places to consume takes the burden off of law enforcement and ensures that people aren't penalized for enjoying something that is recreationally legal or medically necessary.