Planning June 2019

Adventures in the Land of OZ

The federal Opportunity Zone program is helping funnel money into underinvested neighborhoods — and the time to get involved is now.

By Minjee Kim, PhD

Since the Great Migration of the early 1900s, Bronzeville has served as the economic and cultural hub of Chicago's African American communities. The one-time home of civil rights advocate Ida B. Wells, Pulitzer-prize winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks, and author Richard Wright, the South Side neighborhood is rich with architectural landmarks, cultural institutions, and prominent businesses.

But Bronzeville has suffered from a lack of new investment, population decline, and consistently high unemployment rates, even as other parts of the city emerge from the Great Recession. According to the Economic Innovation Group, that's a prevalent pattern across the country: uneven economic recovery, both geographically and across different income groups.

Local community development groups have been working to breathe new life into the neighborhood. Now, the new Opportunity Zone federal tax incentive could help.

"One of the things that excites me about this program is that equity capital is now chasing projects located in the neighborhood where I've been working," says Lennox Jackson, founder and CEO of Urban Equities, Inc., a Chicago-based real estate development firm. For Jackson, the Opportunity Zones program aligns perfectly with his mission to build responsible real estate development projects throughout Chicago.

Jackson is in talks with equity investors to develop a 53-unit workforce rental housing project targeting renters making 80 percent of the Area Median Income, which translates to an asking monthly rent of $1,800 for a 1,050-square-foot two-bedroom apartment. The equity capital is coming from an emerging class of investors showing interest in low-income communities across the nation. Those investors are attracted by the OZ incentive, which promises higher after-tax returns on their investment.

It's the injection of capital that neighborhoods like Bronzeville need, says Jackson, who has been working for more than 20 years to revitalize the area, not only as a community-focused real estate developer, but also as the director of the Bronzeville Community Development Partnership. Up until now, attracting investment has been extremely challenging, he says.

For Lennox Jackson, a developer based in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago, the Opportunity Zones program aligns with his mission to build responsible real estate projects throughout the city. Photo by Alyssa Schukar.

The OZ tax incentive is new — and has some of the usual growing pains that come along with that. One was the lack of clear tax regulations to take advantage of the incentive, which has been largely resolved due to the second set of regulations released by the IRS in April 2019. Another, experts say, is the lack of shovel-ready projects ripe for investment. There is also an urgency factor: Investors can reap the most benefits when they invest by the end of 2019, as the maximum amount of capital gain exclusion requires seven-year investment, a threshold that must be met by the end of 2026.

Known officially as the Investing in Opportunity Act, it was created as part of the 2017 tax bill, formerly known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Its aim is to generate new flows of capital into communities persistently suffering from disinvestment. Investors, for their part, receive significant tax benefits when they reinvest capital gains (like money earned from selling stocks or most other assets) into low-income census tracts designated as OZs.

To be eligible for the tax benefits, investors need to invest in vehicles called Qualified Opportunity Funds. QOFs must deploy capital in one of two ways. Fund managers can purchase stocks or take a partnership interest in a business located in an OZ, or directly purchase tangible property used in trades or businesses within an OZ. Investors must meet minimum requirements for either option:

- Ninety percent of QOF assets must be in either of the forms discussed above: as stock or partnership interest in businesses located in OZs (if the QOF invests in subsidiary businesses), or as tangible properties within OZs, if the QOF itself operates a trade or business directly.

- For a qualified OZ business receiving investment from QOFs, 70 percent of its tangible property must be qualified OZ business property and 50 percent of its gross income must be derived from the active conduct of a trade or business in the OZ (employee work hours/wages can also be used to satisfy the gross income requirement).

Exactly what qualifies as OZ business property is highly complex and context specific, and requires advice from tax attorneys and accountants.

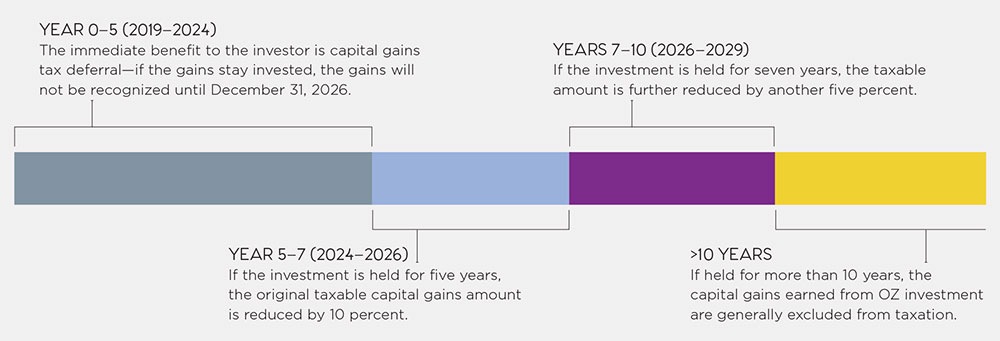

How a Qualified Opportunity Fund Works to Benefit Investors: Individuals and businesses that sell an asset subject to capital gains taxation (for example, stocks, bonds, or real estate) can receive tax benefits if the gains are invested in a Qualified Opportunity Fund.

Questions and answers

OZs are quite new, and not altogether understood. But that doesn't mean planners, investors, developers, and other interested parties are waiting around.

The concept emerged in 2015. It was developed by the Economic Innovation Group, a public policy think tank and advocacy organization based in Washington, D.C. Congress included parts of the Investing in Opportunity Act in the tax bill that passed in December 2017, and the IRS released the first set of regulations delineating many of the fine points of the law in October 2018, with the second set following in April 2019.

From a planning perspective, some policy advocates are questioning the accountability and likely community impact of the program. Researchers in think tanks like the Urban Institute and Brookings Institution, and affordable housing advocacy organizations such as Enterprise, have voiced concerns that the OZ incentive, as enacted, contains no mechanisms or guidelines for tracking where the money will go and the types of projects that will get funded. This makes it impossible to understand what impacts the investment will have on the low-income communities the program was designed to help.

Michael Novogradac, a managing partner of Novogradac & Company and a well-known expert in federal tax credits aimed at helping underserved communities, has a more positive outlook. He anticipates that a "third tranche" of IRS guidance is likely to tackle such data collection and reporting issues.

Even as the rules of the game are being defined, capital has already started flowing into designated OZs. "There is no problem with money, the problem is the deals," Kaya Bromley said at the Opportunity Zone Expo in Los Angeles in January.

"It's hard to find deals that are shovel-ready that fit all the requirements," she adds. Bromley represents CommunityVentures|RE, a Nevada-based real estate consulting firm whose mission is to foster real estate developments that make positive social impacts. Other industry experts at the Expo — investors, fund managers, and attorneys, as well as for-profit and nonprofit developers — echoed her position that money is chasing projects.

Interest among the investment community is continually gaining traction. CoStar, one of the largest information providers of the real estate industry, reported in February 2019 that some of the largest real estate equity investors are hurriedly moving into OZ and launching funds that will be worth billions of dollars combined. Why the rush? The way the program is structured means that gaining the biggest incentives requires starting now.

So time is running out for planning professionals and policy makers to take preemptive steps to ensure that this new flow of capital becomes a catalyst to help existing low-income communities, rather than fueling gentrification and displacement.

Who created these Opportunity Zones?

In December 2017, governors were given 90 days to nominate a list of census tracts to be designated as OZs. "Eligible tracts" were defined as tracts with a median income of 20 percent to 80 percent AMI, and each state was allowed to nominate up to 25 percent of the eligible tracts. Governors also had the option to include "contiguous tracts," defined as tracts adjoining the eligible tracts with a median income at or below 125 percent AMI (limited to five percent of the total designated tracts).

The nomination process varied widely from state to state. Many did not administer a formal process for soliciting local and community input, given the short time frame. In Massachusetts, cities had just 30 days to recommend census tracts within their jurisdiction and residents could submit a nomination request online. Florida instituted a set of minimum principles, such as making sure there was at least one OZ is in every county. Comments and designation requests were considered on an on-demand basis thereafter.

California initially took a data-driven approach, which led to selections that did not fully capture the actual needs of the eligible tracts, such as one where a large student population drove down the median income. The state eventually revised their nomination after soliciting and incorporating comments from the public.

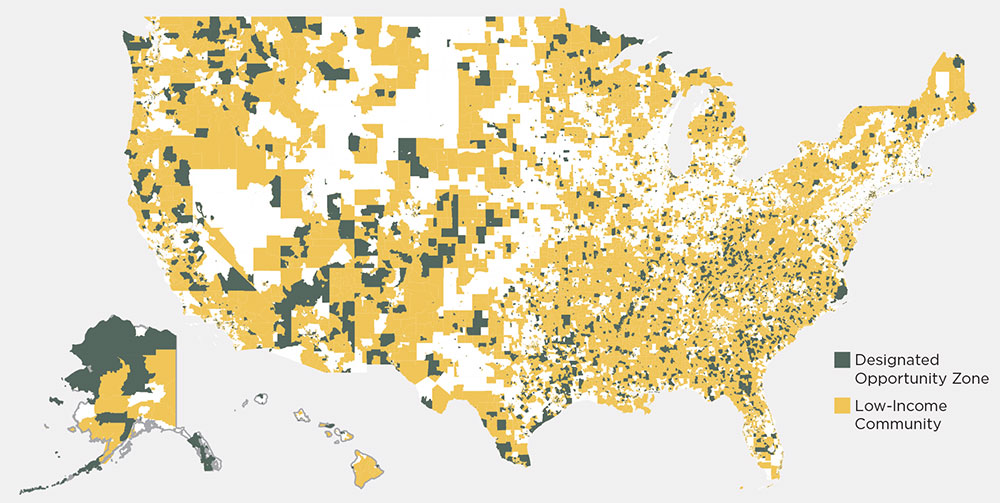

In June 2018, just six months after the nomination process started, the U.S. Treasury finalized the OZ designations certifying 8,762 OZs across the country. That is equivalent to 12 percent of U.S. census tracts.

Opportunity Zones From Coast to Coast: The OZ incentive generally allowed governors to designate up to 25 percent of a state's low-income community population tracts as qualified opportunity zones. There are 8,700 in the U.S.; an interactive map by zip code is available. Map courtesy Novogradac & Company LLC.

Time is quickly running out

While questions are still being resolved, there is a sense of urgency. This is because according to the IIOA, investors will recognize their deferred capital gains in 2026. This essentially means that the end of 2019 is the deadline to take advantage of the seven-year tax benefit. Investors will have until the end of 2021 to be eligible for the five-year tax benefit and they will be eligible for the 10-plus year tax benefit as long as investments are made by December 31, 2036, and held for at least 10 years; the gains must be realized by the end of 2047.

Why should planners and policy makers pay attention?

The fact that institutional investors are looking into heretofore underinvested neighborhoods holds great potential for encouraging economic and community development there.

Community-focused developers, like Lennox Jackson of Urban Equities, are seeking to take advantage of this option. Jackson hopes that his current portfolio of OZ projects will serve as a platform to prove to investors that he can deliver healthy returns, which will help him to attract further investment. His firm has two other projects in Chicago's OZs and he believes that these projects together have the potential to stimulate economic revitalization at the neighborhood level without displacing or marginalizing existing communities.

However, the biggest caveat of this powerful new tax incentive is that there currently is no mechanism to encourage, let alone ensure, that investments will help existing low-income communities. For example, fund managers of Qualified Opportunity Funds can develop luxury apartments or student housing, rather than affordable or workforce housing, as long as the projects are located in OZs. Given that market-rate projects are likely to promise higher investment yields, the OZ program has the potential to fuel gentrification while bypassing those in need.

What concerns Jackson most is that the "matchmakers," matching deals with investors, "don't even know how to look for companies like mine." In his view, the typical matchmakers, such as real estate and tax attorneys, brokers, and economic development corporations, are just going to work with the same types of people and projects, unless they are encouraged to do otherwise. OZ investment is likely to initiate and accelerate gentrification and displacement if the public sector does not step in to correct the anticipated market-driven course of outcome.

Erie, Pennsylvania's Guiding Principles

Erie's OZ projects seek to foster cultural diversity and vibrant neighborhoods. Photo courtesy Flagship Opportunity Zone Development Company.

Erie's Flagship Opportunity Zone Development Company works to cultivate and promote projects with positive social impact. Erie looks for projects that encourage:

Cultural Diversity

- Provides for inclusivity of the diverse set of residents

- Positively contributes to the identity of the neighborhood or city

- Has a plan to include a diverse set of stakeholders

- Provides for minority-, women-, or veteran-owned businesses

Welcoming and Vibrant Neighborhoods

- Meets with neighborhood organizations/stakeholders and provides opportunity for public input

- Aligns with existing city plans and neighborhood strategic plans

- Includes employment opportunities for the neighborhood

- Has an affordable or workforce housing component

- Cleans up a blighted or underutilized area

- Enhances public space

- Increases access to high-quality products and services to neighborhood residents

- Positively contributes to the identity of the neighborhood or city

Education

- Improves the likelihood that young people will stay in Erie

- Addresses the negative effects of brain drain

- Includes components of financial literacy and/or home buyer education and equity training

Design and Operational Best Practices

- Provides for on-site rainwater retention

- Achieves LEED, WELL Building Standards, or Portfolio Manager Technical Reference standards (or an equivalent)

- Goes above and beyond regulations relative to indoor and outdoor air pollution, light pollution, and/or passive design

What can or should planners and policy makers do?

Both state and local governments have critical roles in shaping the flow and the use of OZ capital. Most importantly, public leadership needs to highlight investment opportunities with positive social and environmental impacts to further the tax incentive's original intent: to promote economic growth and revitalization in disinvested parts of America for the benefit of existing low-income communities.

PROMOTE SHOVEL-READY PROJECTS THAT HAVE SOCIAL IMPACT

Public agencies should strive to become alternative matchmakers, identifying and marketing opportunities that promise good financial returns and help existing low-income residents to grow. The public sector must first identify their priorities, which could include developing affordable and workforce housing or supporting minority-owned and legacy businesses, for instance.

The leadership role undertaken by Erie, Pennsylvania, is exemplary in this regard. "We truly care about inclusive and equitable growth," says Brett Willer, the director of capital formation at Erie's Flagship Opportunity Zone Development Company. "We tried to be intentional ... so that we are cultivating and promoting projects with positive social impact." Flagship is advised by a committee composed of civic leaders representing business, government, and community interests, which evaluates potential projects' financial viability and social impacts then actively promotes such projects to potential investors.

CREATE NEW FINANCIAL INCENTIVES OR LEVERAGE EXISTING ONES

New financial incentives, such as preferential treatments on state-level capital gains tax and local real estate tax and grant programs, can propel OZ projects. Existing incentives can also be leveraged. At the state level, existing tax credit programs such as New Market Tax Credits, Historic Tax Credits, and Low-Income Housing Tax Credits can be aligned with the OZ program to make it easier for developers to tap into multiple incentives at the same time.

At the local level, tax increment financing and municipal bonds can be leveraged to channel the flow of OZ-induced investment into the projects that are most in need. In Washington, D.C., Mayor Muriel Bowser committed $24 million for OZ-derived projects that support affordable housing, workforce development, and the growth of small businesses.

CONSIDER PUBLICLY OWNED LAND

State and local governments can think strategically and creatively about government-owned land within OZs. For example, parcels can be leased or sold to developers at less than market value for an affordable housing project. Governments, therefore, need to have updated databases of publicly owned land, identify the types of developments they would like to see on these sites, determine what potential public subsidy packages might look like, and select and work with development partners.

EXPEDITE THE ENTITLEMENT PROCESS

Fast action matters to developers and investors in OZs because significant improvements must be made to the property within 30 months to be eligible for tax benefits.

In 2018, California passed a bill exempting projects financed by Qualified Opportunity Funds from the state's environmental impact review when certain requirements are met. Similarly, local governments can set up a designated unit within their planning and zoning division to oversee OZs and offer expedited review processes. Long Beach, California, has created an online mapping tool that shows where OZs overlap with areas where expedited land entitlements are allowed and where certain land-use regulations may be waived.

The road ahead

In a program where there are still many unknowns, there remains a particularly thorny problem to tackle: How to encourage an equitable distribution of investment across communities with varying market competitiveness, when states and localities have to compete for scarce resources.

Several journalists and policy advocates have aired concerns that OZ capital will inevitably flow into the urban neighborhoods that hardly need the help. The Boston Globe reported in May 2018 that two Massachusetts OZs located in Somerville have real estate markets that are already "thriving," teeming with recently completed, under construction, and planned real estate developments.

In contrast, the same article shows little optimism for OZ-driven investment to make an impact in the state's "Gateway Cities" like Fall River or New Bedford — older, smaller, formerly industrial cities in desperate need of investments.

State and local leadership will become all the more important in balancing the spatial distribution of OZ-induced investments. States can establish a clearinghouse for OZ investors and highlight the places and projects anticipated to make a greater social impact.

This again means that states need to identify their priority projects and places, baking those priorities into their selection criteria for awarding additional incentives or preferential regulatory treatments. Although no state has yet to step up to such a level of civic leadership, many, including Maryland, have created map-based platforms where projects looking for OZ investment can upload their development proposals, making it easier for potential investors to find deals to invest in.

Actions taken by local governments will also make an impact. In places where the real estate market is already strong, localities can adopt or strengthen their regulatory exaction programs, such as inclusionary zoning, linkage fees, and hiring and wage standards. Such action will not only help localities to maximize the exaction packages but also encourage developers and investors to turn their attention to alternative investment opportunities that they might not have considered otherwise.

The land of OZ, as some would call it, is still largely uncharted terrain. This, in fact, presents an invaluable opportunity for planners and policy makers to make a meaningful impact.

Well-crafted public policies and interventions will become the keys to unlock the positive effects of OZs. It is time that planning engages deeply with the equity concerns surrounding OZs and takes bold steps to ensure that OZ-induced capital reaches the places that need it the most and is used for projects and activities benefiting existing low-income communities.

Minjee Kim is an assistant professor of land-use planning and real estate development at Florida State University.