Planning March 2019

Planning for Action

Communities in crisis take on affordability with Housing Action Plans.

By Kristen Pope

Long before Santa Rosa, California, lost 3,000 housing units — five percent of its total housing inventory — in the October 2017 Tubbs Fire, the city already faced a monumental housing crisis. Construction was at historically low levels following the Great Recession, and units were scarce and out of reach for many low- and middle-income residents. A "hard urban growth boundary" put in place to protect open space made things even more challenging according to Clare Hartman, AICP, deputy director for planning in Santa Rosa's Planning & Economic Development Department.

Local officials recognized that a more concerted effort was needed, so in 2016 they tried a different approach. The city spent the next year developing a comprehensive Housing Action Plan. Unlike traditional housing plans, which tend to focus on a single issue (such as homelessness) over a shorter time frame, Housing Action Plans take into account the full range of a city's housing challenges — which are often interconnected — to set priorities, identify solutions, and build a long-term, holistic plan of action. Housing Action Plans have the added benefit — and challenge — of uniting a wide variety of community stakeholders and governmental departments around the same cause.

For these reasons, HAPs are rapidly becoming the tool of choice for communities looking to solve local housing crises, from large eastern cities like Philadelphia (pop. 1.5 million) to small mountain towns like Big Sky, Montana (pop. 3,000), and wine-country cities like Santa Rosa (pop. 175,000).

Rebuilding of homes is under way in Santa Rosa after the 2017 Tubbs Fire. The city's original Housing Action Plan has had to evolve; an urgency ordinance helped streamline the permitting process in the rebuild area. Photo courtesy City of Santa Rosa.

Evolving priorities in Santa Rosa

Rosa Fortunately for Santa Rosa, the social and political will to tackle the Housing Action Plan undertaking were there from the start. In 2016, the city council declared "Housing for All" and "Homelessness" as Tier 1 local priorities, which set the Housing Action Plan into motion.

The planning process, led by Planning and Economic Development Director David Guhin, involved extensive collaboration across city departments. Santa Rosa's planning staff also held numerous study sessions with the city council and community and stakeholder meetings to formulate clear goals that would help them work toward solutions.

"You have to have unanimous council support and you have to have interdepartmental leadership to make it happen, because it does take the whole of the organization to make it work," Hartman says.

The planning process culminated in October 2016, when Santa Rosa's HAP was officially released. Among its goals are aims to increase affordable housing, focus on "affordability by design," and prepare for more development. The plan endeavors to build 5,000 units by 2023, half at market rate and half in the affordable to lower or moderate range. Additionally, the city seeks to preserve 4,000 affordable units, "facilitate and revitalize" 2,000 unbuilt housing units, and plan several other measures.

But just when everything seemed to be going according to plan and the city was moving forward with implementation, the Tubbs wildfire roared through the city, destroying 3,000 housing units.

"Our Housing Action Plan has had to evolve with the resilient city strategy and rebuild strategy," Hartman says.

An urgency ordinance helped streamline the permitting process, allowing people to receive counter permits for some projects and expedited reviews for others. There have been significant gains: During a year-long period starting in October 2017, 69 homes were completed, with 837 more under construction in the rebuild area. Hundreds more are in permit review or have been approved. Additionally, hundreds of other permits were issued during the first 10 months of 2018 outside the rebuild area, including 342 single-family units and 186 multifamily units.

The city is also encouraging the development of two kinds of housing in particular: accessory dwelling units and downtown residential units. ADUs are a key part of Santa Rosa's housing strategy because they meet a HAP goal ("affordable by design") and also fulfill the city's requirements to provide moderate income units under the city's state-mandated Regional Housing Needs Allocation. A key step? Removing regulatory obstacles to ADUs, including one of the largest: fees.

Prior to 2018, impact fees for a 750-square-foot ADU topped out at $22,000 (similar to those for single-family houses). Today, fees total just $4,000. The city also reduced setback and parking requirements to make ADUs more practical. The results speak for themselves: The planning department used to issue an average of six ADU permits per year. In the months post-fire and following the December 2017 policy changes, the number of applications soared. Property owners last year applied for permits to add 118 small living spaces adjacent to traditional single-family residences, according to new city data.

Santa Rosa also aims to add more than 3,000 housing units downtown, where the General Plan and Downtown Station Area Specific Plan call for higher densities. To stimulate development, Hartman says the city is considering fee reductions for "building up" and creating housing over office spaces, supplemental density bonuses for parcels near the rail station, and other, even greater incentives for providing affordable housing.

Next on the city's list, according to its latest annual report published in April 2018, are a number of pending HAP actions, from creating a modular housing pilot program and funding and implementing land-banking programs to amending hillside development standards and considering adding a nondiscrimination ordinance that would apply to residents with housing vouchers.

Throughout the setbacks, pivots, and wins, Hartman found partnerships and common ground among stakeholders crucial. "When you really start seeing all of those stakeholders agreeing on the type of project that you're promoting, you really start to realize you found the sweet spot," she says.

Santa Rosa: Rebuilding and Evolving

Rebuilding activity under way in Fountaingrove, a hillside community of Santa Rosa, in October 2018 — a year after the devastating wildfires. Santa Rosa's Housing Action Plan: srcity.org/HAP. Photo courtesy City of Santa Rosa.

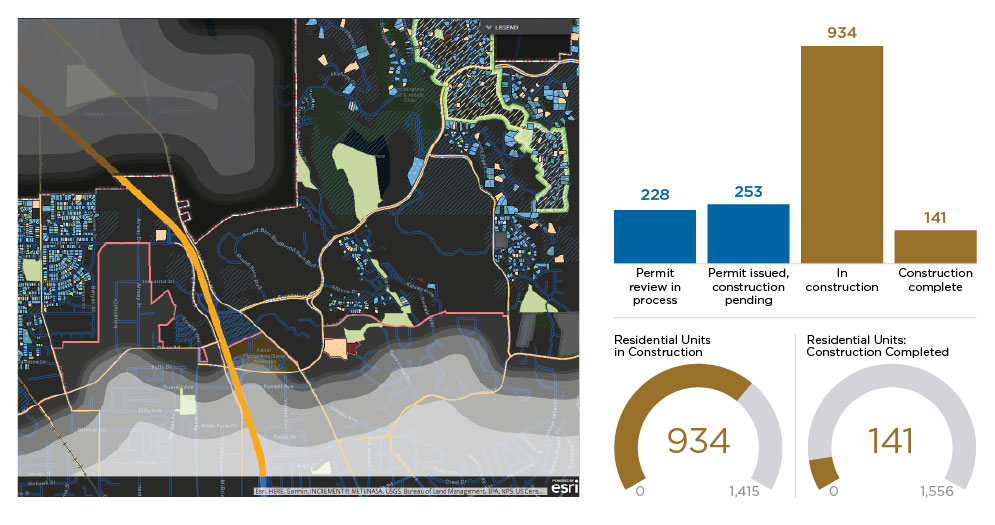

Resilient City Fire Recovery Progress

Santa Rosa's Resilient City Recovery maps are updated daily and provide snapshots of the residential housing rebuilding efforts. This map and data are from January 28, 2019.

Source: City of Santa Rosa

Long term in Big Sky

More than 900 miles northeast of Santa Rosa, Big Sky, Montana, is experiencing a particular kind of housing crisis. The resort community attracts skiers and snowboarders from around the world in the winter, along with warm weather tourists in the summer. Around 3,000 people make Big Sky their year-round home, and it is located 40 miles from Bozeman, a city with more than 46,000 residents and home to Montana State University.

Like many resort communities, Big Sky's housing challenges center on seasonal tourism. The town's popularity as a winter destination has proven a double-edged sword. Property values have skyrocketed in recent years. At the same time, local workers struggle to find and afford places to live, while up to 70 percent of residences sit vacant most of the time — used as seasonal residences or short-term rentals instead of long-term rentals for local employees and residents.

"Big Sky has been one of the highest and fastest growing VRBO and Airbnb markets in the country," says Laura Seyfang, program director for the Big Sky community Housing Trust. "We were number one last year, in terms of both rentals and the increase in number of units put into that pool."

According to the February 2018 Community Housing Assessment and Needs report, the median cost for a condo or town home is $390,000, plus the cost of monthly HOA fees, while the median single-family home sale price is more than $1 million. Rental units cost an average of $2,500 a month, which requires an income of at least $100,000 per year to afford — three times what the average local hourly waged worker earns.

"A lot of folks who work here [have been priced] right out of the market," Seyfang says.

Recognizing the unsustainability of the situation, Big Sky hired consultants to examine its housing sector, study other mountain towns, survey the community's needs, and develop a plan. The Housing Action Plan format presented "an excellent framework for guiding implementation of strategies," says Seyfang.

The first part of the five-year HAP, the Community Housing Assessment and Needs report, set the goal of adding 655 units within five years, with more than half priced below market rate, to close the existing workforce housing gap. It includes an additional 250 to 300 units by 2023 to keep up with new job growth, but needs will be regularly evaluated.

Thus, the town's HAP rental efforts will target households that earn below the area's median family income of $70,000, and home ownership efforts will primarily focus on households earning less than $120,000. However, the Community Housing Assessments and Needs report cautions that figures do not account for roommates living together — an arrangement that constitutes 40 percent of Big Sky households — which means the actual average household income is likely even lower.

The Housing Action Plan also aims to leverage the 70 percent of existing units that sit empty most of the year to increase resident occupancy above 30 percent. While a committee of local stakeholders is currently examining ways to encourage property owners to shift to renting to locals on a long-term basis, Seyfang notes that short-term rental owners may be willing to shift to long-term rentals if they receive support, such as resources to find qualified long-term renters. She also says many owners' belief that short-term rentals will bring in more money as opposed to renting longterm to locals is often a misconception.

"We've done the math, and it's not significantly more money," she says. "It kind of depends on the level of your unit, but we're not talking about the high-end units. That's not where our local workers want to live or can afford to live."

She also points out many people renting properties via the short-term rental sites are unknowingly operating outside state requirements to obtain a license and pay state rental and resort taxes on those properties — restrictions that longer-term rentals are not subject to — which could be added incentive.

Seasonal employers are pitching in, too. The area's two largest employers, Big Sky Resort and Cross- Harbor Capital Partners, a conglomerate that owns several local ski resorts, provide an array of housing options for their workers, including dormitory-style housing, rental units, and even renting out rooms in hotels and inns. The Big Sky Community Housing Trust is working with local employers to brainstorm additional solutions, although this collaboration is not part of a formal partnership program.

It's still early days for the implementation of Big Sky's HAP, but Seyfang says these recent efforts are a step in the right direction. "The reality is it's a very big problem, and it has many moving parts, and there's not just one solution," she says. "We didn't get here overnight, and we're not going to fix it overnight. It's going to take a concerted effort."

Big Sky, Montana: Finding Affordable Housing for Local Workers

Big Sky's housing challenges center on seasonal tourism. Local workers struggle to find affordable housing, while up to 70 percent of residences sit vacant most of the time — used as seasonal residences or short-term rentals instead of long-term rentals for local employees and residents. The Housing Action Plan targets rental efforts on households that earn below the average median income of $70,000 and home ownership efforts for those earning less than $120,000.

Photo by Mark LaRose, courtesy Big Sky Chamber of Commerce.

Renter Income Distribution Compared to Available Rentals

| Income Level As % of AMI* | Maximum Income | Maximum Affordable Rent | Renter Income Distribution | Available Rentals (12/2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <=60% | $36,210 | $905 | 25% | 0% |

| 60-80% | $48,280 | $1,205 | 13% | 0% |

| 80-100% | $60,350 | $1,510 | 10% | 29% |

| 100-120% | $72,420 | $1,810 | 14% | 0% |

| >120% | >$72,420 | Over $1,810 | 38% | 71% |

* Average Median Income in Big Sky is $70,000.

Home Owner Income Distribution Compared to Available Homes

| Income Level As % of AMI* | Maximum Income | Maximum Affordable Purchase Price | Owner Income Distribution | For Sale Listings (12/2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <=60% | $36,210 | $142,000 | 4% | 3% |

| 60-80% | $48,280 | $189,300 | 5% | 0% |

| 80-120% | $72,420 | $284,000 | 16% | 6% |

| 120-150% | $90,525 | $355,000 | 17% | 6% |

| 150-200% | $120,700 | $473,400 | 21% | 8% |

| >200% | >$120,700 | Over $473,400 | 36% | 76% |

* Average Median Income in Big Sky is $70,000.

Preservation in Philadelphia

Founded in 1682 and home to more than 1.5 million residents, most of Philadelphia's housing challenges are related to an aging housing stock and a high poverty rate (26 percent) that creates intense demand for affordable units. But from 2008 to 2016, the city lost 13,000 lower-cost units to rising rents — 7,000 in the last two years alone — while adding 6,000 high-end units. Confronted with these numbers and the projected growth of 25,000 additional households over the next decade, local officials and planners had to switch gears.

Previous efforts had included several specific plans for homelessness, eviction prevention, home ownership, and other issues, as well as a consolidated annual plan to receive HUD funding. This time, they decided to use a different, more comprehensive type of plan: A draft of the city's first HAP — Housing For Equity: An Action Plan for Philadelphia — was released last October.

"We decided to do an action plan to cover the [full] spectrum of housing issues in the city, from homelessness through to market-rate housing," says Anne Fadullon, director of Philadelphia's Department of Planning and Development. She notes the plan is concise with clear goals and specific programs and policies to meet them. "The key word of this plan is action," she says.

Philadelphia's HAP focuses on several key themes and programs, including housing the most vulnerable, focusing on long term affordability, helping people become home owners, fostering growth without displacing residents, and helping to rehab and preserve areas.

Seven working groups are collaborating on the project, with elements ranging from helping small landlords make repairs, a down payment loan fund, and helping residents, including the elderly, make adaptive modifications so they can stay in their homes.

The ambitious plan will involve 100,000 units over the next 10 years with an objective of 3,650 new housing opportunities per year and preserving 6,350 units each year.

High levels of poverty are a challenge; in 2017 alone, the city saw 24,000 eviction filings. Nearly 43,000 people are on the wait list for the housing authority. Many units also need a significant amount of work — 31,000 units don't have full kitchens and 27,000 lack complete plumbing. "Our biggest challenge really is we're a very poor city," Fadullon says. "A very large percentage of our housing stock is 50 years or older, so you combine old housing stock with lower-income folks and it's very hard to maintain that housing stock."

Rather than simply pushing for new units, the city is focusing on helping residents stay in their current units and improve living standards when necessary. "The most affordable unit is oftentimes the unit you're already in, so it's really incumbent on us to do whatever we can to help make sure people can stay in the existing units that they have," Fadullon says.

According to Fadullon, funding is a huge challenge, but she notes the project's visibility has helped garner support from stakeholders. As a result of this discussion and the road map laid out by the HAP, the mayor, with the support of city council, committed to additional funding of $53 million over the next five years and offered support for legislation that would provide an additional $18 million over that time.

"The conversation and effort [around the Housing Action Plan] put the spotlight on the issue, and folks realized, okay, we've got to put our money where our mouth is," Fadullon says.

Philadelphia: Affordability and Staying in Place

Programs and themes in Philadelphia's Housing Action Plan include housing the most vulnerable, focusing on long-term affordability, helping people become home owners , fostering growth without displacing residents, and rehabbing and preservation. Photo by Tiger Productions, courtesy Division of Housing and Community Development.

Age, blight, and vacancies in Philadelphia's housing stock contribute to the shortage of safe, decent affordable housing. Source: Housing for Equity: An Action Plan for Philadelphia. See the proposed Philadelphia HAP.

The HAP proposes strategies to produce 36,500 new homes over the next 10 years, while the Adaptive Modifications Program helps residents with mobility issues stay in their homes. Photo by Tiger Productions, courtesy Division of Housing and Community Development.

Kristen Pope is a freelance writer and editor near Jackson, Wyoming.