Planning December 2020

Infrastructure

From Urban Renewal to Highway Removal

Advocates — and planners — are pushing to tear down the freeways that divided and bulldozed Black neighborhoods.

By Caitlin Dewey

As protesters toppled Confederate statues this summer, Amy Stelly, an artist, designer, and urban planner at firm Studio Dumaine, allowed herself to hope that New Orleans might soon fell its own worst "racist monument."

For much of her life, Stelly, who is Black, has lived in the shadow of the Claiborne expressway, an elevated freeway built through the Tremé, Tulane/Gravier, and 7th Ward neighborhoods. She has fought to tear down the highway and restore this commercial corridor at the heart of Black New Orleans but faced skepticism, indifference, and inertia.

Now, as the nation continues to reckon with other racist aspects of its past, Stelly and other advocates around the country are intensifying their calls for city and state governments to remove the highways that destroyed Black neighborhoods.

Such teardown projects, once seen as fanciful, have gained momentum as the country's highway infrastructure ages and early adopters show off their success. Five U.S. cities have either capped free-ways or converted them to street-grade boulevards in the past three years, and similar plans have been under review in states like Massachusetts, California, and Texas.

Race usually has been a subtext in these conversations. But in the current climate, advocates say it's time for cities to confront and resolve the racist planning decisions their predecessors made 60 years ago.

The six-lane Inner Loop highway that had for decades divided the eastern part of Rochester, New York, was removed and replaced in 2018 with new complete streets. Wikimedia photo by AIP3745.

The change opened up more than six acres to development — and helped spur more than $250 million in walkable projects. Photo by STANTEC.

Over a million displaced

Constructed largely in the late 1950s and '60s, the highway system was, at its outset, perhaps the greatest testament to America's sprawling postwar ambitions. During the initial buildout, the federal government covered 90 percent of construction costs — which encouraged state agencies to build big.

By 1980, there were more than 40,000 miles of road in the interstate system. Highway engineers have since added more than 5,000 miles aimed at speeding up traffic and easing congestion, especially for suburban commuters.

But the new highways met resistance when they reached large and densely populated urban areas. Transportation engineers, eager to link downtown business districts to their expanding suburbs, plotted routes on top of existing neighborhoods and road infrastructure.

Those neighborhoods, as the late urban historian Raymond Mohl documented, were frequently Black. In many cases, city and state planners purposely built through Black neighborhoods to clear so-called slums and blighted areas.

"The highway system, in its planning and implementation, drove a physical wedge through many parts of America," says former U.S. Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx.

In New Orleans, before the completion of the expressway, Stelly says, residents would walk to Claiborne Avenue for everything from groceries and household errands to Mardi Gras parades and funerals. But while officials nixed plans for a similar expressway through the French Quarter, which preservationists opposed, they moved forward with the Claiborne expressway, destroying dozens of businesses and homes.

"This place was the center of the community, and they wiped it off the map," says Jay Arzu, a planning consultant who has researched the history of urban freeways for the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation. "It hurt this neighborhood — and is still hurting it."

Foxx estimates that, in the first 20 years of the interstate highway system, construction displaced over a million people across the country. In Miami, Interstate 95 flattened swaths of a Black neighborhood called Overtown, forcing some 10,000 people to leave their homes. In Nashville, the I-40 expressway demolished 620 houses, 27 apartment buildings, and six Black churches. For residents who remained along the path of the new highways, land values fell and pollution rose.

"The point is, you could pick from dozens of examples," says Joseph Kane, a senior research associate at the Brookings Institution. "You could do a deep dive on Detroit or New Haven or Syracuse. But to me, the bigger story is the number of them. This was a national trend that all types of places are still dealing with."

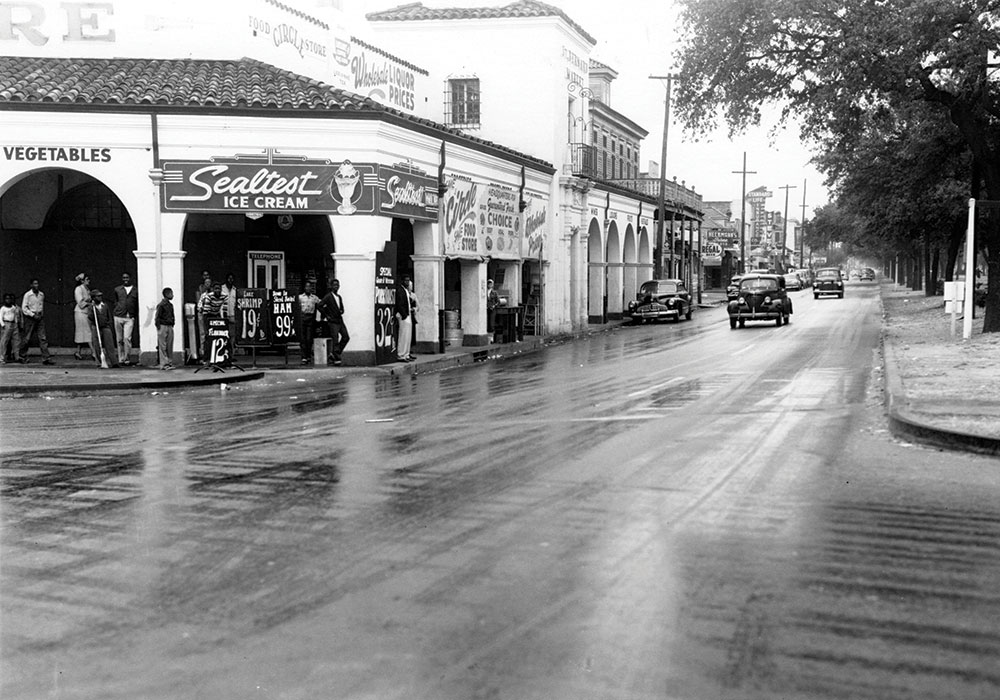

Before the expressway cut through Claiborne Avenue, above, it was lined with old-growth oaks and booming Black-owned businesses. Photo from the Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at the Historic New Orleans Collection, Acc. No. 1979.325.5138.

Under highway 110, the Claiborne Corridor pillars have been painted to honor luminaries from New Orleans's African-American community. Photo by Jamell Tate

An emerging trend

Amid national conversations on race and justice, advocates have intensified their calls for freeway removal. Such projects have gained momentum in recent years, as the country's highway infrastructure requires ever more expansive, and expensive, repairs.

According to the Congress for the New Urbanism, a national nonprofit planning group, at least 14 North American cities have demolished or downgraded their freeways with the help of state and federal grants, and another four had formally started such projects as of this summer.

Those cities include Milwaukee, which demolished a downtown freeway spur in the early 2000s, and Rochester, New York, whose success repurposing the former site of a sunken highway is often cited by teardown proponents. Since removing the so-called Inner Loop in 2017, the city has rebuilt the street grid and parceled out new spaces for affordable housing, retail stores, and a local museum expansion.

"The effort is to try to create a slightly more equitable Rochester," says Arian Horbovetz, a local transportation advocate and blogger. "In removing these highways, we're facing aspects of our racist past. That's the hard part."

But advocates hope more cities will do more of that hard work now, says Arzu, the planning consultant.

Not everyone is on board just yet. Despite calls for change, highway engineers in places like Portland, Oregon, and Birmingham, Alabama, are still widening existing freeways or planning new ones.

State transportation departments generally are most concerned with moving traffic, says Eric Sundquist, the director of the State Smart Transportation Initiative, whose membership includes officials from 19 state transit agencies. And when it comes to traffic, freeways "do a good, if not great, job of moving large numbers of people," economist Randal O'Toole wrote in a July blog post.

Some Black residents also have worried that removing freeways will open their neighborhoods up to new development and gentrification. Ben Crowther, who oversees the Congress for the New Urbanism's freeway removal work, says it is critical that cities use policy protections, like property tax abatements and community land banks, to protect existing residents and avoid repeating old mistakes.

"There is a reckoning taking place," Arzu said. "Anyone who digs deep enough realizes now that urban planning contained a degree of racism in the past."

Caitlin Dewey is a staff writer for Stateline. This story was reprinted with permission from Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Resources

Freeways Without Futures: This regular report from the Congress for the New Urbanism suggests 10 U.S. highways that could be removed to the benefit of local communities.