Planning February 2020

Mind the Gender Gap

Planned mostly by and for men, transit in the U.S. has long failed its most loyal customers: women. But increasing efforts in focused data collection and gender mainstreaming are working to remedy those failures.

By Meghna Khanna, AICP

Does your city's comprehensive plan account for the needs of women?

More than 300 local governments were asked this question as part of a 2014 survey conducted by APA's Planning and Women Division and the Women's Planning Forum of Cornell University to determine whether gender differences factor into local planning decisions in the U.S. The answer, according to an overwhelming majority (98 percent), was no.

These results illustrate what a growing number of planning experts say is a clear and persistent gender gap in the way our cities — largely planned by men — are designed.

"Much attention is rightly paid to how racial and ethnic minorities and low-income households do or do not participate in shaping the future of their communities. Less attention has been paid to uneven planning processes and outcomes by gender," Sherry Ryan writes in a recent PAS Memo, "Integrating Gender Mainstreaming into U.S. Planning Practice." This is despite the fact that "men and women have different wants and needs when it comes to built environments, public services, and amenities, and that planning interventions may not meet all those different needs, especially those of women."

A woman lugs her toddler and stroller up the subway stairs in Queens, New York. Photo by Marian Carrasquero/The New York Times.

The gap is particularly glaring when it comes to public transportation. In the U.S., women account for more than half of all transit ridership, yet their travel patterns and preferences have rarely been accounted for in planning efforts — or even measured.

"Transportation is often where the urban planning gender divide becomes most apparent, as mobility solutions in our cities are designed for the male and able-bodied, resulting in a lot of emphasis on personal, motorized mobility," says Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, a professor of urban planning at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Mobility has a huge impact on the way people interact in and with our communities. By failing to provide women with reliable, convenient, safe, and affordable transportation, cities reduce the economic opportunities of women and negatively impact their quality of life.

Internationally, some South American and European cities are leading a movement called gender mainstreaming, a practice that assesses how planning and policy decisions affect different genders. But while the concept was first introduced and accepted by the United Nations more than two decades ago, it has been slow to catch on, particularly in the U.S.

Fortunately, a number of new studies, including a groundbreaking effort from Los Angeles, are starting to fill in gaps in gender-differentiated data — and building a framework for successful gender mainstreaming in transportation planning.

Public transportation is the only option for many women, even if routes aren't convenient for their commutes and off-peak service is not ideal for errands. Photo by Monica Almeida/The New York Times.

Gender roles and mobility

Historically, mobility has looked different for men and women due to traditional gender roles. Most men were in the paid labor force, while most women were not.

"'A woman's place is in the home' has been one of the most important principles in architectural design and urban planning in the United States for the last century," urban planner historian Dolores Hayden writes in What Would a Non-Sexist City Be Like?

"Most cities were built in such a way that men could go out and work, while women stayed home to look after the kids," she writes. "Coming home was a respite for men, so it was preferred that homes were separate from work altogether, especially since many of the jobs were in dirty or polluted industries."

That meant zoning replaced the suburban potential for mixed-used developments and the traditional street grid with meandering, isolated residential streets lined with single-family houses, miles from stores and businesses. In cities, public transit systems were built by and for the male workforce's typical nine-to-five rush hour commute.

In the decades since, we've seen a significant increase of women in the paid labor force: from around 18.4 million in 1950 to 73.5 million in 2015, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Still, lingering institutionalized gender roles mean their travel patterns continue to differ from men's.

Women spend significantly more time than men on household management and caregiving tasks. Worldwide, they dedicate an average of 4.5 hours a day to unpaid work, much of which occurs outside the home, like grocery shopping. That's more than double the amount of time men spend, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Faced with heavier family responsibilities, women statistically tend to take jobs closer to home, or find employment in service sectors like health care, education, catering, and cleaning, with positions that are part-time, with irregular working hours, or for lower pay. A recent report from the National Women's Law Center found that women account for about two-thirds of low-wage workers in the U.S., despite making up less than half the overall paid labor force.

According to Loukaitou-Sideris of UCLA, these factors contribute to women being the predominate mass transit users across the globe. "Women are captive transit users. If there is one car in the family, it is often driven by the man in the household. Taking a taxi is often too expensive to be an option. For many of these women, public transit is the only transportation mode," she says.

Women tend to bear outsized burdens and risks in the course of their daily travel as they navigate transportation networks to get to school, to work, and to run errands for and with their families.

Much of their transit usage occurs during off-peak services times, when trains and buses run infrequently or eliminate service altogether, and they are often transporting strollers, wheelchairs, and groceries on infrastructure that does not accommodate such items.

Infrastructure changes can help make transit safer. Quito, Ecuador, installed glass bus shelters to increase the line of sight in all directions and eliminate blind spots. Photo by Karl Fjellstrom, Far East Mobility.

So what's being done?

A handful of cities are working to close the gender gap in transportation planning by determining how women use transit and how it can better accommodate those needs. The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (LA Metro), my employer, is the first transit agency in the U.S. to gather and analyze gender-differentiated statistics.

Last year, LA Metro published Understanding How Women Travel (UHWT), a study with quantitative and qualitative data from a variety of sources, including a survey completed by 2,600 residents; pop-up engagements at key rail stations; and workshops with loyal riders women who are immigrants, have disabilities, and are experiencing homelessness.

Our core findings revealed that women use transit more often each day than men, but make shorter trips: potentially driven by workforce participation rates, location of employment opportunities, and household-serving trips that tend to be more localized. Additionally, women are more frequently responsible for the mobility of other family members, particularly children and aging relatives, requiring women to spend more money on fares and find ways to accommodate strollers, small children, and wheelchairs.

Women are also more likely to trip-chain, or tie together small trips into a larger journey plan. In many cases, this can restrict or even prevent the use of public transportation: These complex, nonwork-related trips often occur during off-peak hours, in areas that might not be easily reached by rail or bus routes designed for commuters.

Our findings join a steadily accumulating collection of gender-differentiated data from other cities that have gone a step further and implemented changes based on the information. In Vienna, Austria — an early pioneer of gender mainstreaming — officials distributed a questionnaire about how city residents used transportation in 1999. The men filled it out in five minutes: They went to work in the morning, then came home at night.

But the women couldn't stop writing: about dropping the kids off at school on the way to work, or taking them to the doctor some mornings, or helping their own aging parents buy groceries, or picking the kids up from activities. As a result, Vienna instituted some small but significant changes to the city's infrastructure: wider pavements, ramps for strollers, lighting for safety.

Similarly, in 2012, Transport for London (TfL) used surveys and other engagement strategies to assess women's and girls' travel patterns. Based on the feedback, TfL now offers free travel for passengers under the age of 16 and fare capping to account for trip-chaining. The agency has also outfitted transit stations with ramps and elevators to better support women with strollers, wheelchairs, and other factors that might result in access barriers.

The UHWT study is only the first step in LA Metro's process to better understand and better serve the needs and preferences of female riders. Next comes a Gender Action Plan, which aims to ensure that LA Metro's policies, programs, and activities include a gender perspective. The findings could inform adjustments to LA Metro's fare policy to make it more equitable toward women and more cost-competitive with driving and carpooling; the way transit vehicles, rail stations, and bus stops are designed; and new service offerings that meet mid-day peak travel demands and provide better direct connections over long distances while minimizing transfers.

Spotlight on safety

Further compounding women's access barriers to public transportation is the issue of safety. According to the LA Metro's UHWT study, 20 percent of women bus and rail riders reported experiencing sexual harassment in the past six months. And while 60 percent of female riders feel safe riding Metro during the day, that number plummets to 20 percent at night. Similarly, a 2018 study from the New York University's Rudin Center for Transportation estimated that safety threats cost women around $26 to $50 per month in changed behavior, including avoiding the use of public transportation at night.

To make transit safer, the report recommends creating better monitoring and reporting tools for riders, along with involving women in the design of transit stops to make them safer from the start.

Some transit agencies have started this work. Recently Buenos Aires, Quito, and Santiago joined forces in a push to make transit safer and more gender inclusive. The effort resulted in the 2019 FIA Foundation and CAF Development Bank survey, Ella se mueve segura. Un estudio sobre la seguridad personal de las mujeres y el transporte público en tres ciudades de América Latina, which found that at least 60 percent of women across the three cities reported feeling unsafe on public transit. The joint effort allowed the cities to share their results, challenges, and solutions, resulting in the creation of stricter laws to prevent and punish harassment, plus infrastructure changes, like installing predominately glass bus stops to eliminate blind spots.

In Toronto, the Transit Commission's Request Stop program improves rider safety by allowing woman traveling between the hours of 9 p.m. and 5 a.m. to be let off between stops closer to their destination. The agency has also expanded the program to protect other potentially vulnerable groups, including the elderly, youths, the disabled, people of color, and queer people.

London is leading all global cities in understanding and operationalizing gendered mobility differences and launching major antiharassment initiatives. The London Underground and the Docklands Light Railway have added an extra 200 British Transport Police (BTP) officers to address women's safety concerns.

And through a joint initiative with BTP and other area police departments, TfL launched a public awareness campaign in 2013 called Project Guardian that used social media to raise awareness of the rampant problem. The Twitter hashtag #ProjGuardian illustrates clearly that experiences of sexual harassment are not a rarity or a one-off. Thousands of women are sharing their stories, all of them demonstrating that this has become an accepted part of our experiences as women in public. Such efforts are particularly timely given the increased attention to sexual harassment in the #MeToo era.

Because incidents are found to be widely under-reported, the program also instituted a confidential hotline and text-message service to encourage victims and witnesses to come forward. The following year, BTP reported a 21 percent increase in sexual harassment — which meant that more people were reporting crimes, and more perpetrators were being held accountable.

"Women's stories of harassment and assault have upended the way that we think about public space, including the space that we share on trains, buses, and sidewalks," says LA Metro's UHWT report. "In holding ourselves responsible for those transportation spaces, we redefine what an inclusive mobility network could look like in the future."

Meghna Khanna is a senior director with the Countywide Planning & Development Department at LA Metro. She served on LA Metro's Women & Girls Governing Council as the leader of the Service Provider Group and co-led the Understanding How Women Travel study.

LA Metro Study Uncovers Transit's Overlooked Gender Gaps

In 2017, Los Angeles Metro joined a handful of transit agencies in the U.S. working to close the transit gender gap. First, it established the Women & Girls Governing Council to analyze how Metro's programs, services, and policies impact the lives of these populations in Los Angeles. A year later, the agency moved forward on seven WGGC recommendations to cultivate inclusive hiring practices and improve women's and girls' experiences on Metro, including conducting the study Understanding How Women Travel.

Released in August 2019, the study is a comprehensive, intersectional effort to identify the mobility barriers and challenges women face — and the first of its kind in the U.S. Select study findings and methodology techniques are below.

The Findings

Women Aren't the Minority

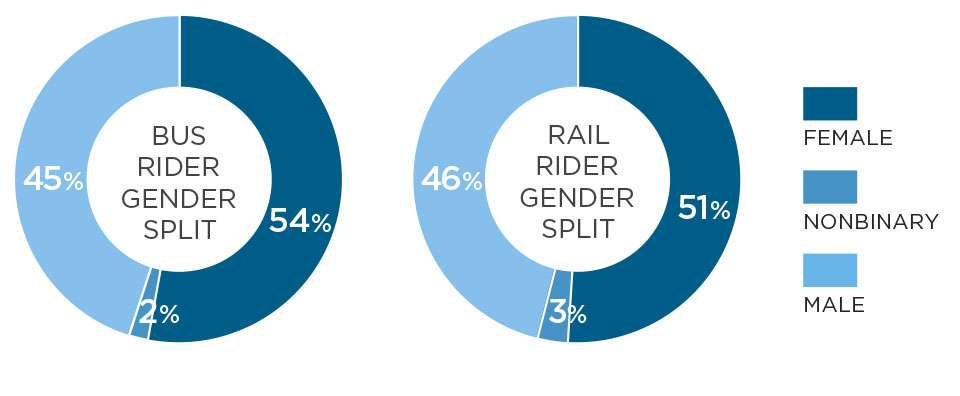

LA transit users reflect national trends: Women account for most of the riders on buses and trains. In addition, they account for a larger share of ridership now than they did in 2010, while male ridership has decreased.

Gender split of Metro bus and rail riders:

Sometimes Public Transit Isn't Enough

Regardless of income, 70 percent of women surveyed have used a ride-hailing service at least once. More than half say they use it for trips transit doesn't serve.

How do you use ride-hailing services in relation to public transit:

Lower Income Means Higher Spending

Women with household incomes under $25,000 shoulder a disproportionate transportation cost burden. They report spending more on monthly transit expenses across the board.

Average monthly spending on transit for self:

Average monthly spending on transit for others:

Harassment Is on the Rise

More female riders reported experiencing sexual harassment within the past six months in 2018 than 2014. Riders who identify as nonbinary reported the most harassment overall.

Metro riders who have been sexually harassed in the past six months:

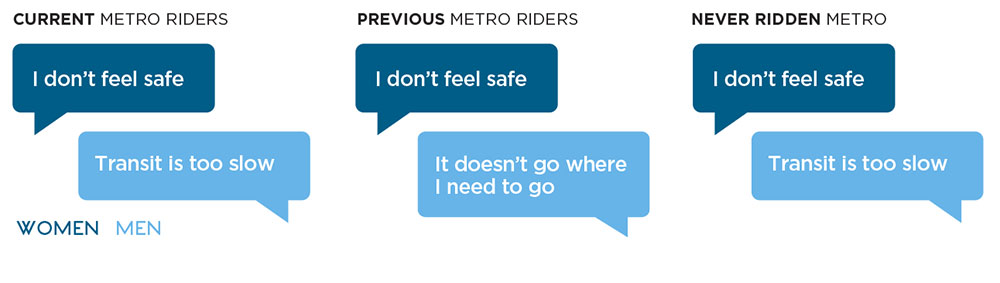

Women Don't Feel Safe

When participants were asked why they don't use public transit, safety concerns dominated the women's responses — but not the men's.

The largest barrier to riding transit in the LA region:

The Methodology

The study used existing data sets and five data collection methodologies to connect with core transit rider groups that may be difficult to reach through conventional methods. Conventional methodologies included focus groups and a survey of 2,600 respondents with an oversampling of women from 400 zip codes.

Innovative Methods (Ethnographic)

Participant Observation

During the fall of 2018, a team of observers spent time on buses, trains, and in stations and took notes on predetermined areas related to women's travel on Metro, gathering information on 2,251 riders.

Photo from Understanding How Women Travel Study (2019).

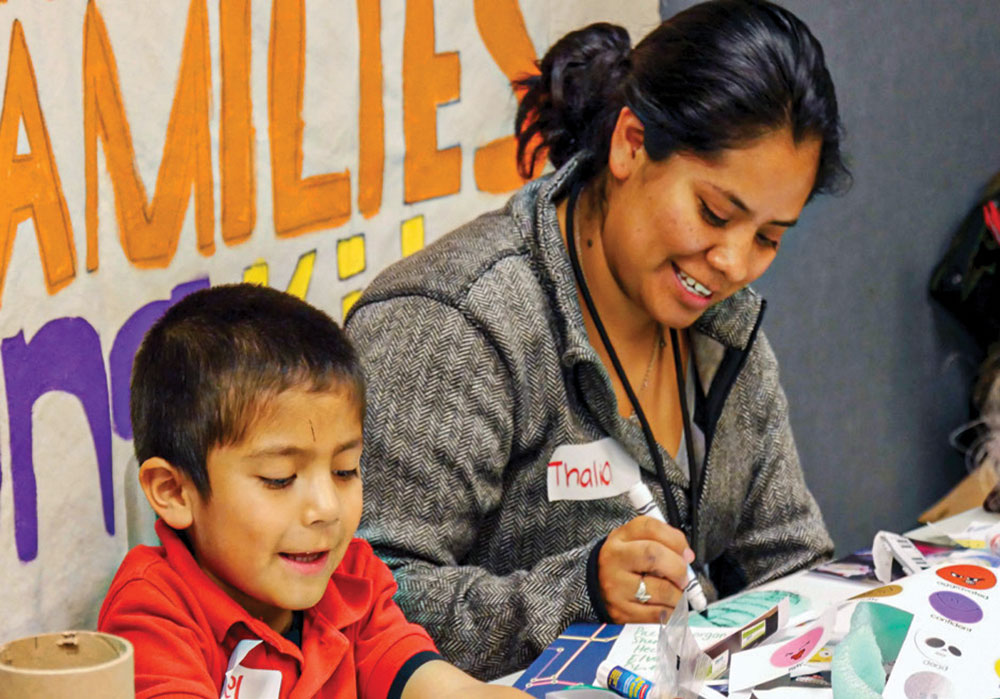

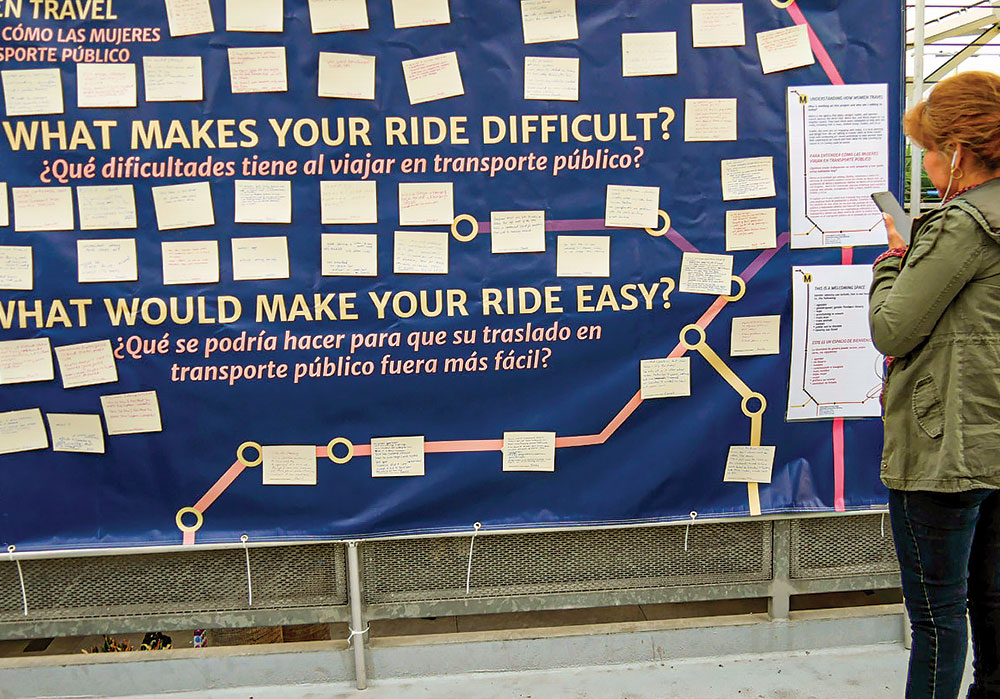

Workshops and Pop-Ups

In 2019, a series of design workshops with community-based organizations gave participants a chance to share their experiences riding Metro. Pop-up engagement activities at transit facilities gave women a chance to sound off on two very important questions (below).

Photo from Understanding How Women Travel Study (2019).

Source: Understanding How Women Travel Study (2019)

Three Lessons from the Leader in Gender Equity

From left, photos from Shutterstock/Nobelio; Muellek Josef (two photos); Rafaelzenato.

By Michael Podgers

Planning for all genders isn't just about transportation. For 30 years, Vienna has been creating a more gender-inclusive city — and their efforts have proved to not only be successful, but durable. Here's a look at the takeaways from Vienna's long-running policies and projects:

1. Do Your Research

The impetus for Vienna's gender mainstreaming was anecdotal: a photo exhibit in 1991 exposed how differently women experienced the city than men. Early advocates were inspired to incorporate women's experiences into planning decisions and successfully convinced the city to adopt the practice. Soon after, the city began collecting quantitative and qualitative data to examine how, why, and when men and women use the city and provide an objective base for gender mainstreaming efforts.

The data produced a multi-lens look at the city. For example, park research revealed that girls often stopped using sport facilities as teens because boys were exerting more control over these spaces by moving in large groups and playing more physical sports. Designers have since created more welcoming parks for girls by incorporating sports facilities they desired (like tennis courts) and semiprivate social spaces (like shaded seating). Such changes made Vienna's parks more welcoming to families with small children, older residents, and people with disabilities, too.

2. Representation Makes a Difference

In Vienna, signs around the city were changed from depicting the typical cartoon man to showing explicitly diverse figures participating in public life. Construction signs feature women workers, walking path signs depict fathers holding children, and an elderly man (who resembles Sigmund Freud) sits beside a pregnant woman on priority seating signs on transit. Crosswalk signals use a variety of figures including men, women, and couples of different gender combinations.

While widening sidewalks to make them universally accessible or designing parks to encourage girls to participate provide big changes, these visual tweaks are visible daily — and act as powerful symbols. They signal the values of a city to residents and visitors and should be incorporated widely and unambiguously.

3. Focus on the Beneficiaries, Not the Politics

To lead Vienna's gender mainstreaming efforts, the city established a municipal office for women's issues (the Frauenbüro) in 1992. The early office was influenced by feminist theory, which alienated skeptics and frustrated some activists who believed gender mainstreaming reinforced stereotypical gender roles. To better navigate competing interests, the city began emphasizing the benefits of the program, not the politics of it.

For example, a 1997 pilot led by the Frauenbüro invited a team of women architects to design a public housing development that showed how incorporating women's ideas, experiences, and concerns produced better results for all types of family units. It has since been replicated.

In another instance, the Frauenbüro team acknowledged it was necessary to have allies in male colleagues. Although a hard pill to swallow, male colleagues sometimes have had to act as spokespeople when working with less receptive audiences. Despite the many visible accomplishments in Vienna, compromises still had to be made to achieve results.

Vienna's example is a reminder of the power of focusing on deliverable goals and outcomes when faced with politically fraught change.

Michael Podgers holds a master's in Urban Planning and Policy from the University of Illinois at Chicago and has lived in Vienna.