Planning January 2020

Holistic Houston

In the wake of Hurricane Harvey, the city is redefining its approach to resilience planning.

By Perla Trevizo

Houston is no stranger to extreme weather and its impacts. In 2001, Tropical Storm Allison killed 23 people across Texas and caused more than $9 billion in damage. Seven years later, Hurricane Ike became the third-costliest hurricane in U.S. history, leaving many in the region without power or access to food and medicine for weeks. In 2015, the same year the Memorial Day flood killed seven people and required more than 500 high-water rescues, the Washington Post named Houston one of the most flood-prone cities in the U.S.

Then came Hurricane Harvey.

Harvey made landfall in August 2017 as a Category 4 storm and hovered over the region for days. Some areas saw more than 50 inches of rain, and more than 150,000 homes flooded in Harris County. At least 36 people died across the county, while estimates put the recovery costs at $125 billion — second in the country only to Hurricane Katrina, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Harvey signaled a new normal, forever changing the region's views of rainfall and flooding and what it truly means to be resilient. Those views were further solidified two years later when Tropical Storm Imelda dumped more than 40 inches of rain on some areas, killing five people and flooding at least 17,000 homes. According to scientists at Texas A&M University at Galveston and the University of Oxford in the UK, climate change made the storm 10 to 15 percent more intense.

"Ten years ago, a mayor in Houston probably wouldn't be talking about climate change, maybe even five years ago, maybe even three years ago," Mayor Sylvester Turner said in July, the Houston Chronicle reported.

Today, confronted with the reality of increasingly frequent and intense rain events, sea-level rise, and rising temperatures, Houston is taking strides to address its climate vulnerabilities. The city is working toward its first climate action plan, has hired a chief resilience officer, and continues to invest in flooding mitigation and prevention. Together, these policies mark a transformative new approach to resilience for Houston — and the beginning of an arduous, necessary effort to make it the kind of place that can recover from floods while also providing a safe, equitable future for all of its residents.

In Houston, resilience doesn't just mean recovering after a disaster. It means involving all aspects of community life and health. Photos by Jim Wilson/The New York Times and courtesy Discovery Green/Katya Horner.

Holistic approach

August 29, 2018, a few days after Harvey's first anniversary, marked a key turning point. The city was named the 101st member of the global nonprofit network 100 Resilient Cities, funded through a $1.8 million grant from Shell. 100RC, pioneered by the Rockefeller Foundation in 2013, prepared localities worldwide for hazards and socioeconomic challenges by helping them hire chief resilience officers, developing strategies, offering technical assistance, and providing a platform to share best practices. Though 100RC sunsetted in July, the global Resilient Cities Network has an $8 million new grant to continue to support participating cities like Houston.

Houston's first chief resilience officer, Marissa Aho, AICP, joined the city staff in February 2019. In her first 10 months on the job, she has guided the Resilient Houston process, the city's multiphase effort to develop a formal resilience strategy — and with it, a more holistic perspective of what must be addressed to build a truly resilient city and region: extreme weather and water management, of course, but also housing, mobility, infrastructure, and the economy — all with an underlying focus on equity. A draft outline of the strategy was released in September 2019 for public comment.

"It's usually not done this fast, but part of it is that Houston is really ready to implement and make changes," says Aho, who is also an AICP commissioner.

The assessment identified issues like flooding, extreme heat, drought, hazardous material incidents, and an oil and gas downturn. Chronic stresses, they found, came down to poor transportation and education quality, lack of affordable housing, and aging infrastructure. Based on meetings with stakeholders and input from the community, five major themes emerged: equity and inclusion, health and safety, housing and mobility, infrastructure and economy, and living with water and climate change.

This holistic view of resilience represents a marked change since Houston's unsuccessful attempts to join 100RC network prior to Harvey. Then, the city defined resilience as addressing flooding and drainage, says Brett Perlman, CEO of the Center for Houston's Future, a nonprofit focused on making the Houston region globally competitive. But to the Rockefeller Foundation, it meant much more.

After Harvey, flooding was still on people's minds, but stakeholders began to think more broadly, says Perlman. For example, they saw how the issue of affordable housing was exacerbated after the storm. Before Harvey, 14,226 people were on the Houston Housing Authority public housing waitlist; after the storm, that number jumped to 112,559, FOX 26 Houston reported. Some residents couldn't replace their flood-damaged cars; that affected many other aspects of their daily lives, including getting to work.

"When we break down resilience, ultimately we want to keep folks in their homes," and if that's not possible, then in their neighborhoods, says Aho. That can include buy-in and buy-out programs that keep people in their school district or figuring out a way to have neighborhoods provide more housing choice as people's life circumstances change. If a major disaster strikes and people can't stay in their neighborhoods, she says, the aim is to keep people in the city.

That focus on equity is also evident in the draft of Resilient Houston, which outlines a series of goals and actions to be implemented over the next several decades. Chapter One, "Prepared and Thriving Houstonians," has three goals with 12 actions; some are concrete, like preparing residents for an uncertain future by developing cash and direct assistance programs for vulnerable populations during disaster recovery or for weatherizing existing homes and properties. Others are broader, such as creating a plan for pedestrians to make streets safer. The draft strategy also addresses equity in neighborhoods, healthy and connected bayous, becoming an adaptive and accessible city, and forming an integrated region.

"It's not only about preparing to rebound from a disruption, which tends to be the definition of resilience a lot of people latch on to, but it really is making sure the system can perform adequately in advance," says Kristina Ronneberg, senior planner in the transportation department at the Houston-Galveston Area Council.

To achieve that, it's important that every piece of the resilience effort connects with what others are working on, says Aho. "We're stitching everything together to make a big quilt."

City Resilience Framework, Houston Style

The Resilient Houston assessment establishes drivers that measure the city's ability to withstand a wide range of shocks and stresses. Houston will use the framework to identify areas of strength and weakness, investigate the comprehensiveness of a challenge or solution, organize data, and measure progress while evaluating and leveraging existing programs such as Plan Houston and the Complete Communities Action Plan.

Source: Resilient Houston Resilience Assessment

Work in progress

As part of that big quilt, the city tied initiatives that were already planned or underway into the resilience strategy, Aho says, with the goal of aligning new efforts with existing and emerging initiatives.

For example, in 2018, Houston began mandating that all new homes built in the region's floodplains be elevated two feet above the projected water level in a 500-year storm, in what Mayor Turner called a "defining moment" for the city, the Houston Chronicle reported. Turner is also trying to increase investment in green infrastructure; in August, he announced incentives to help fight flooding and water pollution through techniques including rain gardens and green roofs. This includes adopting rules that "harmonize parking, landscaping, open space, drainage design, detention design, and stormwater quality design requirements," deferring or reducing property tax bills for developers using green stormwater infrastructure, and providing a faster plan review process, with lower fees associated with projects that use green stormwater infrastructure.

Tech may help. Last March, a Smart City Advisory Council was established to speed up the adoption of technology and data-driven practices, like real-time air quality monitoring and better communication with residents about high-water areas, for instance. These align with the resilience strategy's priorities, including improving residents' quality of life and preparing them for an uncertain future.

Perhaps one of the biggest signs of shifting perspectives in Houston is the pending release of the city's Climate Action Plan (expected at press time by the end of 2019) that sets a goal of becoming carbon-neutral by 2050 in accordance with the Paris Agreement through building optimization, energy transition, materials management, and transportation. On the transportation front, public infrastructure for electric vehicles and alternative renewable fuels will be pursued. To help with the energy transition, the plan proposes powering municipal operations with 100 percent renewable energy and strengthening the city's tree planting and greenspace protection policies. It also calls for a requirement that all city-owned or occupied buildings be designed and operated as net zero by 2030.

In order for the plan to work, the city will need the collaboration of the entire community. In Houston, the state and federal governments primarily control many of the regulations that impact these efforts, so the Climate Action Plan will not be a binding document. For things outside the city's control (like requiring that buildings be net zero by 2030, or switching its bus fleet to electric vehicles), the plan will simply offer recommendations and guidance.

The plan is a vital part of the city's resilience efforts because they go hand in hand with sustainability, says Lara Cottingham, Houston's chief sustainability officer. With climate change, cities can't just rebuild after a disaster. "You have to build forward, because the next thing is going to be different and potentially bigger," she says.

A Quick Tour of Houston's Flood Prevention Projects

While water management is no longer the only resilience focus in Houston, it rightly remains a priority. A variety of existing and current projects showcase some of the creative ways the city is reducing the risks associated with flooding — and creating green public spaces in the process. If you're in the neighborhood for NPC20, take a look.

Bagby Street

Photo courtesy D. A. Horchner/Design Workshop, Inc.

The 10-block reconstruction of Bagby Street has completely transformed the Midtown neighborhood. Once a four-lane, one-way thoroughfare, the street is now a mixed-use corridor with green infrastructure that helps alleviate upstream drainage in the downtown area by transporting stormwater along to the Buffalo Bayou. Bagby Street is the first Texas project that has been certified by the GreenRoads Rating System through its incorporation of permeable pavement, bioswales, and rain gardens (above). Start at Bagby Park and walk east or west along Bagby Street.

Buffalo Bayou

Photo by Jonnu Singleton/SWA Group.

With its ubiquitous path through the heart of Houston, Buffalo Bayou has become the model for integrating the city's bayou systems with adjacent communities. Buffalo Bayou offers trails and various park amenities (like Lost Lake and the Dunlavy, pictured above) while connecting to some of Houston's most important arterial roads, including Memorial Drive, which stretches for about 20 miles between highways.

The bayou was designed for high storage and conveyance capacity while also providing green spaces and recreational areas that easily recover after flooding. In the future, the bayou could be extended even farther east of downtown. Head to Eleanor Tinsley Park Bridge by the Tolerance (Plensa) Statues.

North Canal

Photo courtesy Plan Downtown Report.

For years, a North Canal High Flow Diversion Channel project has been under consideration with the aim of reducing flooding downtown and along the White Oak and Buffalo Bayous. FEMA approved the latest concept in October. The new design, which is currently in progress (above), consists of three portions: two high-flow channel diversions (North and South Canals) and upstream bridge and channel improvements. The alignment of the North Canal will be near the confluence of White Oak and Buffalo Bayous, while the South Canal will be further downstream. The bridge and channel improvements include the elevation of Yale Street and Heights Boulevard bridges to provide additional conveyance capacity and protection to areas along White Oak, including I-10 west of downtown Houston.

Through these phases, hydraulic and hydrologic analysis indicates that the project can remove a large portion of the 100-year floodplain, plus protect flood-prone residences, businesses, and government buildings downtown. Walk along the bayou trails near the White Oak Bayou Trail Crossing bridge.

Willow Waterhole

Photo by Bill Burhans/Willow Waterhole Greenspace Conservancy.

Located in the Westbury area at the intersection of South Post Oak Road and South Main Street, the Willow Waterhole (above) is comprised of 290 acres of integrated stormwater storage, wetlands, and recreation. It provides flood relief to adjacent communities, but also offers Houstonians a place to experience nature. Go to 5201 S. Willow Dr. or 5300 Dryad Dr. (two entry points with different features).

Long road ahead

While the city is heading in the right direction, Houston still has a lot of work to do. One area it can focus on is developing partnerships to help bolster low-income energy efficiency programs, says Stefen Samarripas, senior research analyst for the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, an advocacy group that pushes for lower carbon emissions. Houston ranks 35 out of 75 in energy efficiency, according to the annual scorecard released by the group, which looks at a city's local government operations, community-wide initiatives, and transportation operations, among other factors.

"One of the ways the city could do more is in terms of mandates to increase efficiency in buildings, particularly existing ones," he says. "There are a number of cities in the country putting in place mandatory benchmarks that require homeowners or building owners to take stock of energy use of homes or buildings and disclose it to people interested in buying or renting space."

While funding is an issue for cities, there are alternative models it could consider, says Gavin Dillingham, director of clean energy policy for the Houston Advanced Research Center. Long-term resilience will require new ways of thinking about public and private investment, like green and resilience bonds, he says, which use pay-for-success approaches or demonstrate some level of environmental benefit.

"We've come a long way but still have a long way to go," says Perlman. One of the main challenges, he says, will be remaining focused.

"The focus will always shift to whatever the next problem is," he adds, "but I think quickly bringing people together, looking at best practices, having quick wins so you are implementing tangible solutions people can see, those are all aspects of trying to keep the focus on what's important for the city being proactive as opposed to being reactive."

While Aho's grant-funded job is only guaranteed through 2021, she hopes to bring about long-lasting institutional change. In Los Angeles, where she worked as the first chief resilience officer before coming to Houston, departments work less in silos and see resilience as a value and practice that should be incorporated into everything the city does. There, the mayor executed a directive that included asking about 30 departments to appoint departmental chief resilience officers, which could be an option for Houston, she says.

In the end, "it's really about helping people recognize everyone has a role to play in resilience building, no matter what background you come from," she says. "The government is only one piece of the actions that need to be taken."

Perla Trevizo is a Texas-based journalist. She has covered a range of topics, from county politics to the environment, in a variety of cities and countries.

Complete Communities: Resilience at the Neighborhood Level

In 2017, Houston launched a program dedicated to improving the resilience of individual neighborhoods generally comprised of historically underserved and lower-income residents.

"Complete Communities is about improving neighborhoods so that all of Houston's residents and business owners can have access to quality services and amenities," Mayor Sylvester Turner said when the program was announced. "It's about working closely with the residents of communities that haven't reached their full potential, understanding their strengths and opportunities, and collaborating with partners across the city to strengthen them. While working to improve these communities, we are also working to ensure existing residents can stay in homes that remain affordable."

The program begins with public engagement — "what planners do best," says Margaret H. Wallace Brown, AICP, CNU-A, the director of Houston's planning and development department, which helps lead the collaborative program. "We facilitate a process with the community that identifies their strengths and ways in which they want to improve. We pull together all stakeholders and coordinate closely with other city partners to add value."

An advisory committee with 26 community leaders and advocates serves as a sounding board and ambassadors for the effort, making connections with residents and businesses in the selected neighborhoods. In communities that deal with flooding, the resilience and recovery offices work with residents to find strategies and solutions.

So far, 10 neighborhoods have been selected, five of which have completed action plans, including Turner's hometown of Acres Homes (pop. 55,000), historically one of the South's largest unincorporated Black communities. (See some action plan details, right). There, long-term projects include reducing the unemployment rate by 50 percent by 2023 and building a town square with retail and restaurants.

Initially, Turner redirected a percentage of local and federal housing dollars to the identified neighborhoods. But in 2018, 16 months after the program was launched, the Houston Chronicle reported that Turner was looking for outside entities, like banks and endowments, to underwrite projects through an improvement fund. By June 2019, the newspaper reported that $11 million in donations and "multiyear pledges" had been accepted from banks, corporations, and business interests, with a goal of reaching $25 million.

"We have seen several important improvements and investments in Complete Communities so far," says Wallace Brown. "We have also seen one major nontangible outcome: We are building the community's capacity, and people are talking to each other."

Those conversations are helping to break down operational silos. "It wasn't easy, but we have created a truly collaborative system in which every department seeks ways to contribute and effect change," Wallace Brown says. "I expect we will be using them for many more city-wide initiatives — all for the betterment of Houston."

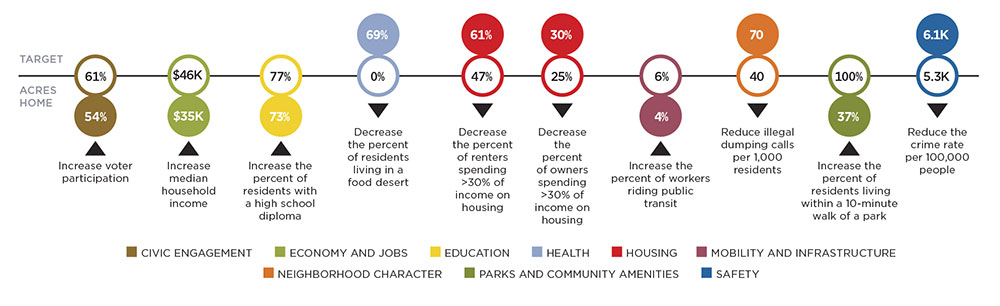

Acres Home Complete Communities Action Plan

Over a six-month planning process, 800 community members worked together at five public meetings to define the action plan's vision and identify 33 goals and 92 projects in nine focus areas. They also set metrics to measure the success in each category, a sampling of which are listed below. See the complete plan. Source: Acres Home Complete Community Action Plan Summary

Complete Communities Success Metrics

Source: Acres Home Complete Community Action Plan Summary

Focus Area: Housing

The Acres Home Complete Communities Action Plan outlines four housing goals and eight total projects aimed at reducing the percent of renters and owners spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing (see success metrics above). The goals and highest priority project under each are highlighted below.

Goal 1: Build New Affordable Homes

Priority Project: Build new affordable single-family housing.

Project Action Steps: Partner with the Housing and Community Development Department and Planning Department to focus new housing on area vacant lots and land bank lots; Identify additional partners or developers to construct new housing at 80% of Area Median Income ($71,500) or below.

Project Timeline: Long (5+ years)

Goal 2: Expand Home Ownership

Priority Project: Grow area homeowners.

Project Action Steps: Connect potential homeowners to Homeowner Education Workshops and Homebuyer Assistance Programs; Identify a partner or local organization to provide HUDapproved courses and workshops.

Project Timeline: Medium (2–5 years)

Goal 3: Ensure Homes Are Safe and Secure

Priority Project: Enroll community seniors, and other eligible homeowners, in home repair programs.

Project Action Steps: Identify and enroll eligible participants in need of home repair in the home repair program provided by Rebuilding Together Houston and Housing and Community Development. Expand the capacity of home repair programs to meet additional needs, potentially through local nonprofit organizations.

Project Timeline: Short (0–2 years)

Goal 4: Grow Local Community Builders

Priority Project: Strengthen existing community development corporations and community housing development organizations, or create a new organization.

Project Action Steps: Organize leaders, CDCs, and organizations to attend the training workshop with Capital One and the Housing and Community Development Department; build the capacity of area CDCs through training, partnerships, and workshops.

Project Timeline: Medium (2–5 years)

Source: Acres Home Complete Community Action Plan Summary