Planning June 2020

Engagement

7 Emerging Tips for Equitable Digital Engagement

Despite the ever-present digital divide, inclusive public outreach and social distancing are not mutually exclusive.

By Michael Podgers

This spring, work changed overnight as governments mandated stay-at-home orders and offices went virtual. For planners long dependent on public meetings and community engagement, this has presented its own set of challenges — especially when it comes to equity. With around 19 million Americans still lacking broadband access and face-to-face outreach on hold, the digital divide has never seemed wider.

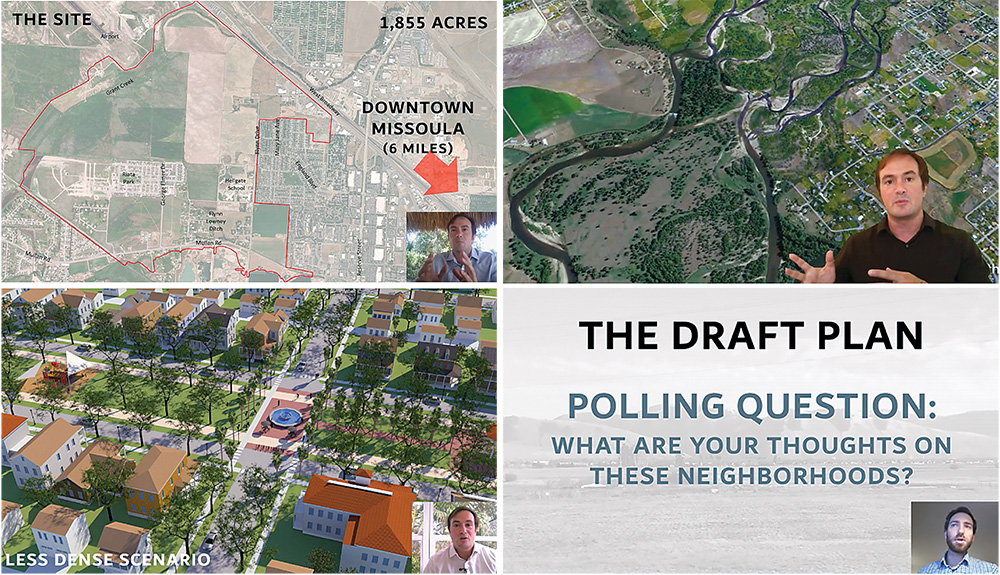

Jason King's (inset) live-turned-digital charrette drew in hundreds more participants than originally expected. In many ways, digital engagement can cast a wider, more inclusive net. Image courtesy Dover, Kohl & Partners.

Pandemic widened digital divide challenge

Here's a look at some of the ways planners and local leaders are keeping engagement efforts inclusive, even while social distancing.

1. Make sure you're mobile-compatible

The pandemic moved too fast to expand broadband access in preparation for social distancing, but people without connections at home might still be online, says Eric Frederick, AICP, vice president of community affairs at Connected Nation, a rural internet accessibility advocacy organization. According to the Pew Research Center, 81 percent of Americans currently own a smartphone. That means all digital outreach efforts must be mobile app compatible, Frederick says. He also suggests making mobile hotspots available to residents to supplement mobile phone internet services.

2. Manage expectations

Chicago Alderman Carlos Ramirez-Rosa advocates standardizing public engagement practices — whether in person or virtual — so stakeholders always know what to expect and will feel more comfortable about participating. "That is important for us," he says. "People can say, 'I know how this works, that I can attend the meeting, that my presence there will be impactful, and I have a sense of what is going to occur.'" Since his office started this practice, residents have become more engaged in local planning, he says.

3. Overcome the in-person bias

Sometimes feedback from digital communications is taken less seriously, says Deb Meihoff, AICP, principal and owner of the Portland, Oregon-based consulting firm Communitas. But while a lack of face-to-face contact might make participants feel less engaged, digital communications are no less genuine, she says. And for some community members, like people living with disabilities, digital platforms have always been easier to use. With more work being done virtually, Meihoff hopes planners can lose their prejudices against digital participation to allow for expanded use, now and in the future.

4. Crowdsource solutions

Alderman Ramirez-Rosa suggests using your community's best resource: the people living in it. He's spent two terms working to make public participation more equitable, but the sudden need to go digital has thrown much of that past work out the window. During his first virtual meeting, he found that one of the biggest issues was providing live translations — a necessity for the Spanish speakers in his constituency. "We are going to bring this to our community group and ask their opinion," he says because they might already be familiar with translation tools and practices his office has yet to test.

5. Take advantage of new opportunities

When Jason King, a principal planner at the Miami firm Dover, Kohl & Partners, made a charrette digital in three days, the result was "a better success" than the original in-person plan. More than 1,000 people viewed the material and provided more than 2,000 comments — far more than the 200 people expected at the live charrette, he says. In-person events often present their long-maligned barriers to equitable engagement, especially when scheduled times conflict with work, caretaking duties, and other obligations. Digital platforms allow participants to respond when it's most convenient for them. King now plans on incorporating digital components into as much of his future work as possible.

6. When in doubt, go old-school

Social distancing doesn't mean everything has to go digital. "We've been talking about going back to some low-tech options," says Meihoff, including phone interviews, mailed surveys with postage-paid return envelopes, and even kiosks with written feedback options located throughout neighborhoods (though this one is a bit tricky, she says, as they need to ensure people don't gather at them).

7. Evolve together

The biggest challenge is coming to terms with the fact that engagement has changed, says Kathleen Duffy, AICP, associate planner at SmithGroup in Detroit. Rolling out virtual community meetings will take the patience to continuously evolve tools and practices, a commitment to making sure solutions work for as many people as possible, and lots of communication — with both your community and your peers. "I think we're kind of just jumping in headfirst," Duffy says, but at least it's together.

Michael Podgers has a degree in urban planning and policy from the University of Illinois at Chicago. He lives in Chicago.