June 17, 2021

More than 50 million people worldwide are living with dementia — a number that is set to nearly double every 20 years, says Alzheimer's Disease International.

People living with dementia (PLWD), like other individuals with disabilities, have the right to be included in the communities in which they live. Unfortunately, the stigma of dementia, often perpetuated by misconceptions of "capacity" or "losing oneself," causes PLWD to be thought of as passive care recipients rather than citizens with voices to be heard, including in public participation in planning. The result is exclusionary built environments and community programing.

Despite the growing number of municipally led age- and dementia-friendly city policies put forward in recent years, calls for accessible engagement of PLWD have not been heeded in planning research. In my recent article, "The Right to (Re)Shape the City: Examining the Accessibility of a Public Engagement Tool for People Living with Dementia" in the Journal of the American Planning Association, I explore a fundamental unanswered question in planning process research: Are the public engagement tools used by planners accessible to all?

In studying barriers and facilitators to participation for PLWD during open houses, I identified several easy, low-cost accommodations practicing planners can make to better engage commonly excluded groups like PLWD.

Breaking it down

According to the World Health Organization, dementia is an umbrella term describing progressive symptoms affecting short- and long- term memory and behavior that can affect spatial navigation, judgment, and visual perception. Two-thirds of PLWD live in their own homes in the community, and their outdoor activity is likely to decrease and be limited to familiar areas as their condition advances (a.k.a. the "shrinking world" effect).

Research shows that PLWD experience built environments differently than older adults in terms of wayfinding, being overwhelmed by noise and activity, and having impaired depth perception and issues with judgment. This evidence also indicates that PLWD's experiences during the planning process might be different.

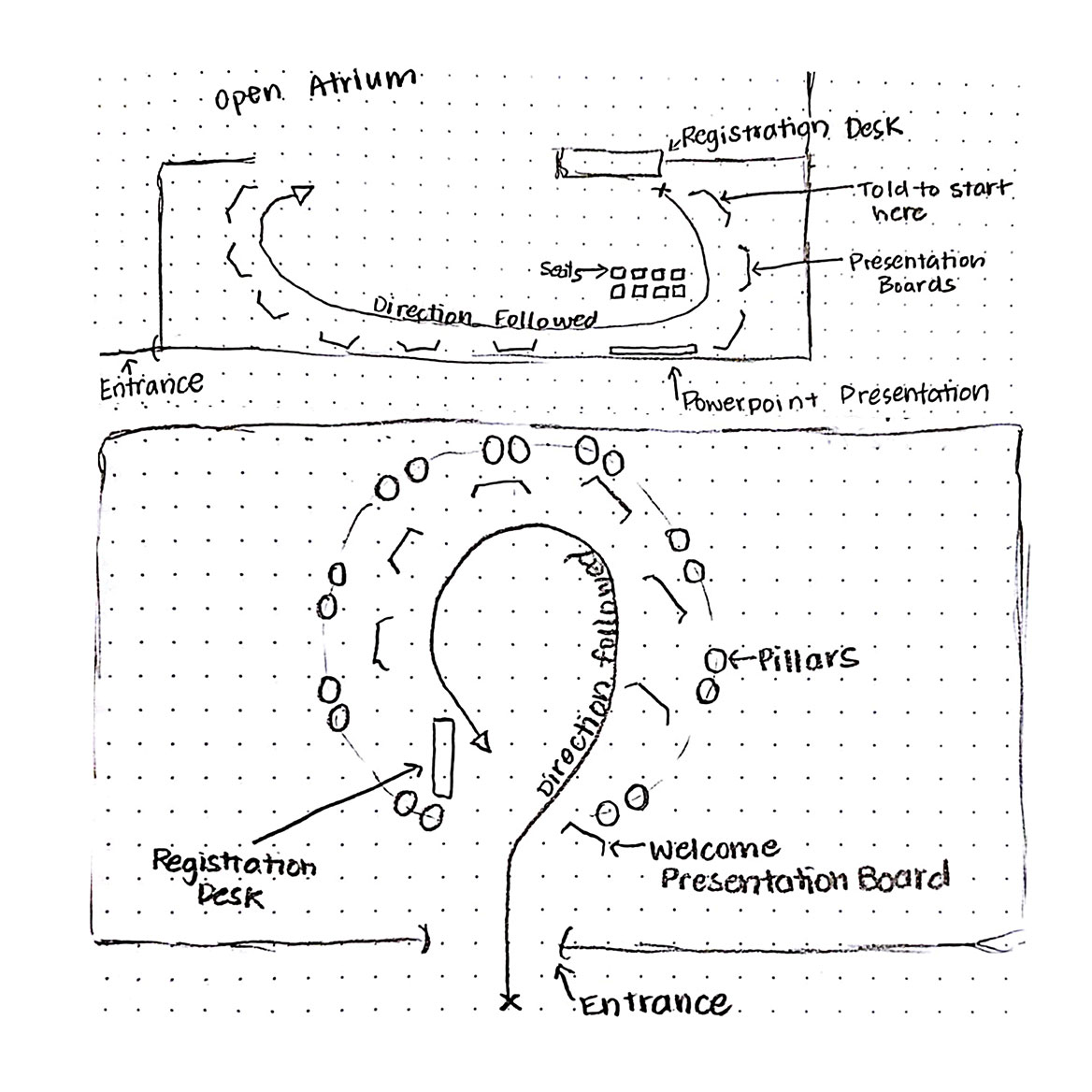

I chose to focus on the open house format in my research because it is a commonly used public engagement tool and — as it turns out — is in many ways already well suited to the accessibility needs of PLWD through peripheral, circular layouts allowing participants to learn at their own pace and interact one-on-one with practitioners. However, the following easily implementable recommendations (organized into three categories) are applicable to a broader set of public engagement mechanisms within a planner's toolbox, including design charrettes and town halls, among others.

Communication

First and foremost, the approach matters. While you likely have multiple demands on your time during an outreach event, it's important to give PLWD your full attention and to be aware of your body language (they prefer open stances). Be patient and respectful by allowing PLWD space and time to understand information at their own pace. Do not prompt them or otherwise make them feel rushed. After a period of silent reflection, if a person still seems to be having difficulty comprehending, ask whether they want something explained or volunteer a digestible piece of information about visual displays. Be sure to avoid jargon.

Physical/Sensory Environment

Room setups, visual aids, and sensory environments can significantly impact PLWD. Visually busy and noisy environments are uncomfortable and distracting, so try to seek spaces that lower the potential amount of noise (e.g., carpeted floors, noncavernous spaces). Ensure the space is evenly and well lit (daylight is preferable), with no reflections on the ground.

Two room set up options with circular layouts. Sketch by Samantha Biglieri.

Event sites should be easy to locate and navigate, with large-format signage with arrows and photographs of the places you are indicating. Within a room, create signs that direct participants to boards, seating areas, commenting areas, registration tables, and washrooms. Set up presentation boards in a peripheral circular formation, clearly indicate the order and where to start, and make it clear how they relate from one to the next.

Exchange of Information

When it comes to information sharing, less is often more for PLWD. Too much extraneous information can lead to confusion, disorientation, and disengagement. Thus, all handouts, feedback mechanisms, and presentations should be clearly and concisely written and, ideally, presented visually with short sentences, plain language, bullet points, large font, and labeled color graphics and photographs. It is also helpful to PLWD to restate the purpose of the event and the feedback desired in all materials. To remove the burden of having to memorize and recall abstract thoughts and concepts, which can be challenging for PLWD, provide options to capture participant feedback "in the moment," such as real-time recording, sticky notes, or emoji stickers to comment directly on materials.

Achieving equitable participation

Planning with PLWD and those in the disability community is attainable — and necessary. By ensuring public engagement tools are accessible to everyone, planners can support community members with disabilities like dementia in actualizing their innate citizenship rights. Equitable participation is a key step in the ongoing fight for accommodation, support, and equitable participation in community and civic life. By adopting these techniques, continuing this type of research, and enabling PLWD to impact decision-making in communities, the planning profession can help dismantle the stigma associated with dementia.