Part of the Disruptors Series

March 1, 2021

Curbs are rapidly evolving, and dense urban areas are feeling the squeeze, particularly when it comes to deliveries. We've all seen a delivery van or on-demand service driver double-parked, pulled over in a bike or bus lane, or stopped in the street. They block traffic or can force cyclists, scooter riders, and pedestrians into oncoming traffic to get around them. It's an accident waiting to happen and difficult to enforce.

How can cities and planners keep all users safe while also fostering commerce and getting the best use out of their curb space? That question led Omaha, Nebraska, which already has some innovative parking programs in place, and five other cities to partner with curb management platform Coord on "smart zones."

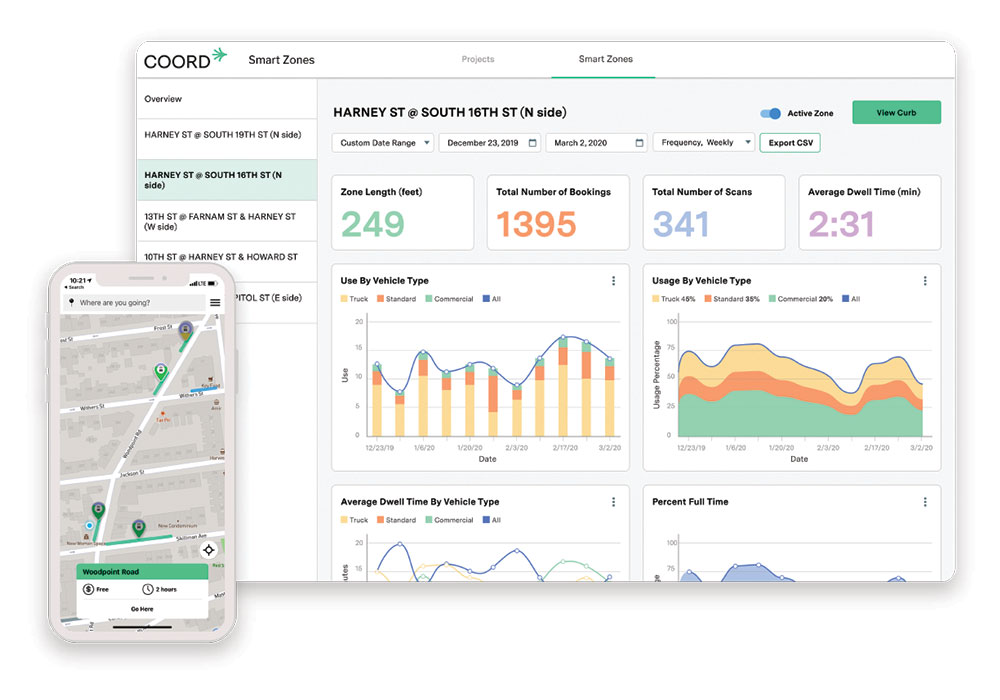

Smart commercial loading zones, or "smart zones," are coordinated through an app that provides drivers for delivery and service providers like UPS and Uber Eats incentive to load in designated locations where it is safe, efficient, and legal — all while collecting data for the city.

More private-sector companies are getting involved in smart city projects, and planners need to learn and understand how to accommodate and integrate them into the planning process.

Smart zones optimize curb use and data

The Omaha pilot, Coord's first, launched last September. Drivers use the Coord Driver app to reserve smart zones along their routes. The app is free, with no outlay costs for participating cities. It also makes it possible for cities to monetize the curb. While Omaha is not currently charging a fee for its smart zones, other pilot cities plan to start at $0.50 to $1.00 for a 15-minute loading trip, a share of which goes to Coord.

"We recommend cities have flexibility to move that price so they can impact supply and demand as they need," says Dawn Miller, Coord's vice president of policy and partnerships.

That's where the data collection comes in. Miller says a lot of the pilot cities lacked data about loading. Smart zones provide a regular stream of data on who is loading, for how long, and on what days and times. Cities can then create tools to manage the curb, whether it's right-sizing their loading space or incentivizing certain windows, which could open up the space for a variety of other uses.

"We want to get a good data set built to see how the curb is changing from parking cars to moving goods and dynamic services like ride share and food delivery," says Kenneth Smith, Omaha's city parking and mobility manager. He sees smart zones as a way his department and other cities can use technology to gather data and make decisions that drive specific outcomes.

The Coord smart zones dashboard allows cities to monitor in real time information on dwell times, occupancy, and compliance. Image courtesy Coord.

Lessons learned

Omaha's pilot hasn't entirely been smooth sailing. With people staying home and working remotely because of COVID-19, downtown parking hasn't exactly been tight, so there's currently not a lot of incentive for drivers to use the app. As a result, they've collected less data than anticipated so far. But, says Miller, the project team has still learned several things to inform what might come next in Omaha and best practices for other cities, including its next pilot in Aspen, Colorado, which launched in November.

For one, the decision to start with five new loading zones created specifically for the pilot (rather than repurpose existing ones) caused an outreach problem. Drivers had no way of knowing about the five new zones, and thus weren't using them or learning about the app. To help get the word out, Coord's team put in some extra effort with street ambassador teams and calls to delivery fleets.

They also realized that future pilots should be bigger to make the smart zones more interesting and useful to drivers. "Because this was the first pilot, we decided to run before we walk, and we did five zones. But there's a network effect, and the system is more valuable the more zones that are on it," says Miller.

Omaha is now looking at potentially expanding the pilot to all 50 of its existing downtown loading zones. Smith sees smart zones as part of a broader effort to study the parking ecosystem of Omaha's urban core, not just for cars but for micromobility as well. "This idea of the smart phone as a service is only going to increase as we go further down the road. I think we're on the right path," he says.

Miller sees smart city pilots like these as great ways for planners to experiment, gather data, adjust plans, and inform larger planning efforts. "It's also okay if things don't go perfectly," she says, because you learn a lot along the way.

Smith adds, "You have to step out and try new things to make decisions that will impact your community. If you don't try, you won't gain the experience."