Uncovering JAPA

Measuring the Early Impact of Eliminating Single-Family Zoning on Minneapolis Property Values

The Minneapolis City Council voted in 2018 to approve a new comprehensive plan that proposed eliminating single-family zoning throughout the city, which at the time made up 70 percent of its total land area, and allowing for triplexes on these properties. Since then the city has found itself at the center of national conversations on housing diversity and affordability.

Eliminating Single-family Zoning Impacts Housing Prices

This attention comes as many planners and advocates seek to address the harmful effects of single-family zoning, including that it produces patterns of racial and economic segregation, encourages ecologically harmful patterns of urban sprawl, and stops the production of the denser housing that most advocates say is needed to address growing housing shortages. While other cities and states have since made similar strides, many are still looking to Minneapolis to see what impact eliminating the single-family designation ultimately has on housing prices.

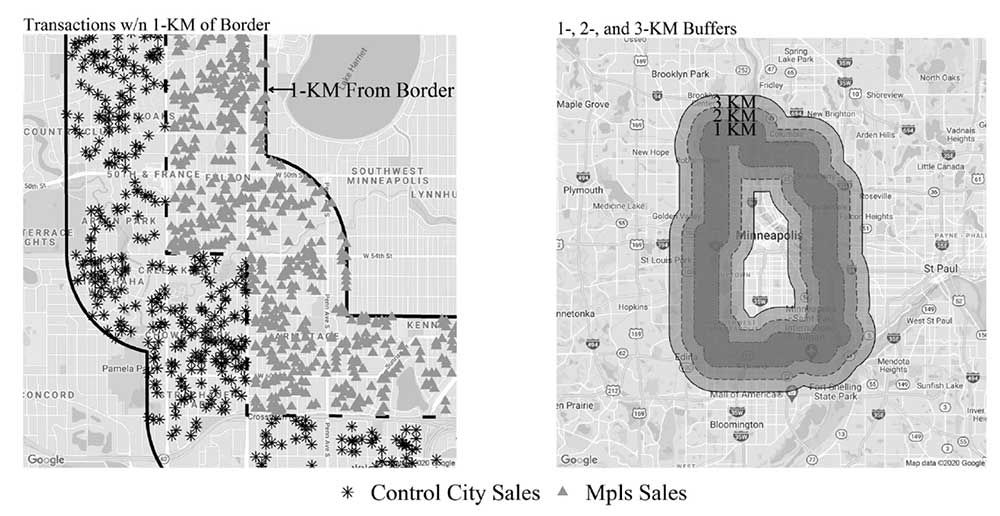

Daniel Kuhlmann offers some of the earliest measurements of this effect in his Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 87, No. 3) article "Upzoning and Single-Family Housing Prices: A (Very) Early Analysis of the Minneapolis 2040 Plan." To do so, he uses a difference-in-differences (DiD) research design that compares the prices of previously single-family-zoned houses in Minneapolis within 1–, 2–, and 3–kilometers of the city border with those houses within the same distances outside of the city border, and not subject to the change in regulation. He measured prices both before and after the city council approved the new comprehensive plan. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Visualization of the buffers.

Property Values Rise After Zoning Change

Across his 3-kilometer threshold, the study finds that the plan's approval increased property sale values of Minneapolis homes by approximately three to five percent. Kuhlmann notes that this increase is to be expected, since greater development potential raises the immediate value of previously single-family properties, even though in the long-term it can encourage a broader housing supply, which can lower city-wide housing prices. Using additional model specifications, Kuhlmann then also finds that these price increases are larger in relatively inexpensive neighborhoods than expensive ones, and for properties that are small relative to the properties surrounding them.

While (very) early, Kuhlmann offers several implications of these findings for planners and housing advocates. First, they suggest that eliminating single-family zoning may indeed raise the values of previously single-family properties that now have greater development potential, which is a significant finding given that many communities resist eliminating single-family zoning over fears that new development will reduce their home values.

These findings also suggest that property owners in relatively inexpensive neighborhoods may see the greatest price increases, which can help lessen the gap between property values. However, the fact that developers are likely to target relatively inexpensive properties compared to properties around them may lead to a short-term reduction in the supply of relatively low-cost single-family housing—though it is too soon to tell if this reduction would outweigh the potential benefits that developing two or three units where there used to be one may have.

Top image: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development